Peter Thiel's Physics Department

Peter Thiel says physics stalled in 1972. Then GPT-5.2 proved a new result in theoretical physics. The 75:1 AI compute gap between commerce and science.

8 min read AIAIBlog about Personal Projects, Articles and Papers on Economics, Finance and Technology

Peter Thiel says physics stalled in 1972. Then GPT-5.2 proved a new result in theoretical physics. The 75:1 AI compute gap between commerce and science.

8 min read AIAI

The Anthropic-Pentagon standoff isn't an ethics story. It's a replay of the 1993 Last Supper that consolidated 51 defense contractors into 5, now playing out at Silicon Valley speed.

8 min read AIAI

I read 12 AI research reports from Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, UBS, and 6 other banks. Here's the consensus they're pushing, and what they're not saying.

10 min read AIAI

Prices rose 25% since 2020 and won't come back. The levels-vs-rates problem explains the vibecession, the Stewart-Thaler debate, and why nobody trusts economists.

7 min read MacroMacro

Novo Nordisk lost 75% since June 2024. CagriSema failed vs Zepbound, US pricing is resetting lower, and Lilly leads on every axis. Full breakdown with numbers.

10 min read MedicineMedicine

A Google insider made $1.15M on Polymarket in 24 hours. Israeli soldiers bet classified strike timing. Why prediction markets need insider trading regulation.

11 min read InvestingInvesting

A 30-second Super Bowl spot costs $8M. The real price is $16–23M. The ROI evidence is mixed. A deep look at the pricing, the prisoner's dilemma, and the NFL.

11 min read EconomicsEconomics

AI converges to the mean by design. On Humanity's Last Exam, top AI scores 37.5% vs human experts at 90%. The data says domain expertise is appreciating.

10 min read AIAI

The EuroPA alliance connected 130 million users across 13 countries overnight. But this isn't really about sovereignty. It's an infrastructure arbitrage exploiting a 100-120bps spread between card network fees and SEPA Instant rails, accidentally protected by the EU's own regulation.

14 min read MacroMacro

One River's data shows beta-adjusted long volatility outperformed the S&P 500 over 40 years. Goldman, AQR, and Universa agree on the mechanism but disagree on implementation. A synthesis of the evidence.

12 min read Quantitative FinanceQuant

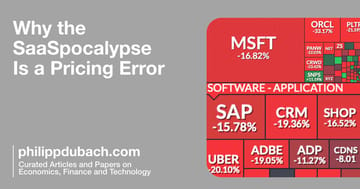

The market is simultaneously pricing AI capex failure and AI destroying all software. Both cannot be true. A data-driven analysis of the February 2026 enterprise software sell-off, the hyperscaler sustainability question, and why Goldman Sachs, a16z, and the All-In pod see a 20x TAM expansion where the market sees extinction.

8 min read AIAI

The enterprise AI agent stack is stratifying into six layers with different winners at each. Models commoditize; context — your organizational world model — compounds. A framework for agentic AI architecture decisions.

7 min read AIAI

Sensor Tower's State of Mobile 2026: apps beat games in revenue for the first time. GenAI added $3.5B. Eight charts on who controls the app economy.

3 min read AIAI

Variance drain is the hidden cost of volatility: why a portfolio averaging +10% can lose money. The ½σ² formula explains the gap between paper and real returns.

4 min read Quantitative FinanceQuant

Claude Opus 4.6 brings a 1M token context window, 68.8% ARC-AGI-2, and Agent Teams to Claude Code. Full benchmark comparison vs GPT-5.2 and Gemini 3 Pro with pricing analysis.

6 min read AIAI

a16z sees AI fundamentals thriving with 80% GPU utilization. AQR sees the CAPE at the 96th percentile. Both have data. Both may be right.

4 min read AIAI

How hybrid recommender systems balance multi-armed bandits against LLM inference cost economics in 2026. A deep dive into Netflix recommendation algorithm architecture and Spotify's AI DJ recommender system.

5 min read AIAI

AQR's 2026 data shows private equity returning 4.2% versus 3.9% for public equities. The 30bp illiquidity premium barely justifies years of lockup.

4 min read Quantitative FinanceQuant

Britain faces strategic isolation: locked out of EU defense cooperation, unwilling to join Trump's coalition. The mid-Atlantic bridge has nowhere to land.

3 min read MacroMacro

At Davos 2026, Carney told allies to take down the signs of the liberal order. Middle powers are learning to navigate between giants without illusions.

4 min read MacroMacro

Sara Hooker's research challenges the trillion-dollar scaling thesis. Compact models now outperform massive ones as diminishing returns hit AI.

4 min read AIAI

85% of AI projects fail. Only 26% translate pilots to production. The winners automate the coordination layer where employees spend 57% of their workday.

2 min read AIAI

Japan holds $5 trillion in foreign assets. With 30-year JGB yields now above 3%, the carry trade that defined Japanese investing faces new friction.

2 min read MacroMacro

Cornell research: GLP-1 users cut grocery spending 5.3%, fast food 8%. With 16% household adoption and savory snacks down 10%, food stocks face headwinds.

4 min read MedicineMedicine

AI was supposed to free us. The Jevons paradox plays out in real time: efficiency expands workload, not leisure. 77% of workers say AI added to their work.

2 min read AIAI

New OFR data reveals $12.6 trillion in daily repo exposures—$700 billion larger than previous estimates. The plumbing of modern money remains poorly understood.

5 min read MacroMacro

Steve Eisman explains how U.S. equity markets have structurally decoupled from everyday economic reality through concentration and passive investing.

4 min read InvestingInvesting

Context windows aren't memory. Explore EM-LLM's episodic architecture, knowledge graph tools like Mem0 and Letta, and why vectors fail for sequential data.

3 min read AIAI

Buffett exits after paying $26.8B in taxes. What 60 years of letters reveal about admitting mistakes, insurance float, and why Abel inherits $300B in cash.

5 min read InvestingInvesting

Apple's $157B cash pile and Gemini-powered Siri shift show a restrained AI strategy. Analysis of whether Apple wins as AI models become commodities.

3 min read AIAI

Rebalancing for 2026: reducing S&P 500 at 40× CAPE, adding Europe after Germany's €1T pivot, and bonds at 4.2% yields. Full allocation rationale.

10 min read InvestingInvesting

Netflix's $72B Warner Bros deal vs Paramount's hostile $30/share tender. Deal mechanics, aggregation theory, and why internet distributors win streaming.

7 min read InvestingInvesting

Nike lost $27.5B in market value by weakening three complementary assets simultaneously. Analysis of how Donahoe's strategy destroyed competitive advantage.

7 min read InvestingInvesting

Michael Burry launches Substack warning AI markets mirror 1999. His Nvidia-Cisco comparison, the GPU depreciation debate, and what hyperscalers need to justify capex.

5 min read InvestingInvesting![Is AI Really Eating the World? AGI, Networks, Value [2/2]](https://static.philippdubach.com/cdn-cgi/image/width=360,quality=80,format=auto/ograph/ograph-eatingtheworld2.jpg)

AGI predictions miss the point. Multiple competing models means price war. Value flows to applications, customer relationships, and vertical integrators.

7 min read AIAI![Is AI Really Eating the World? [1/2]](https://static.philippdubach.com/cdn-cgi/image/width=360,quality=80,format=auto/ograph/ograph-eatingtheworld1.jpg)

Benedict Evans' AI analysis argues 'we don't know how it matters.' But current evidence points to model commoditization: $400B capex, 97% price drops.

5 min read AIAI

Four-day forecasts now match one-day accuracy from 30 years ago. How AI models like WeatherNext 2 use CRPS training to preserve extreme weather signals.

2 min read AIAI

Phase 2 trial shows semaglutide reduces alcohol craving and heavy drinking with effect sizes exceeding naltrexone. What this means for AUD treatment.

2 min read MedicineMedicine

Build an LLM agent in 50 lines of Python. Why context engineering and emergent behaviors are best understood through hands-on experimentation, not theory.

1 min read AIAI

OpenAI lost $11.5B in one quarter. But Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei argues each AI model is independently profitable. Here's why the math is complicated.

4 min read AIAI

Diffusion models corrupt data into noise, then reverse the process. Learn the math with Stefano Ermon's Stanford CS236 course, free on YouTube.

1 min read AIAI![Pozsar's Bretton Woods III: Three Years Later [2/2]](https://static.philippdubach.com/cdn-cgi/image/width=360,quality=80,format=auto/ograph/ograph-Pozsar2.jpg)

Part 2/2: Assessing Bretton Woods III three years later. Evidence shows gradual reserve diversification and gold strength, but also persistent dollar dominance.

6 min read MacroMacro![Pozsar's Bretton Woods III: The Framework [1/2]](https://static.philippdubach.com/cdn-cgi/image/width=360,quality=80,format=auto/ograph/ograph-Pozsar1.jpg)

Pozsar's Bretton Woods III: how Russia sanctions triggered a shift from Treasury-backed reserves to commodity-backed money. Part 1 of 2 on the framework.

7 min read MacroMacro

Michael Mauboussin's argument that every cash-generating asset is valued through a DCF model. Why this Morgan Stanley paper changed how I think about value.

1 min read InvestingInvesting

Agent-based modeling shows how random market transactions naturally produce extreme wealth concentration, and why even a small wealth tax changes everything.

2 min read EconomicsEconomics

A Rutgers study finds news sentiment embeddings from OpenAI models cut stock price prediction errors by 40%. Time-independent models perform just as well.

2 min read AIAI

Amycretin's Phase 1 data shows 24.3% weight loss, beating Wegovy and Zepbound. How Novo Nordisk plans to replace its $20B Ozempic franchise before 2031.

5 min read MedicineMedicine

The zero price effect explains why politicians love free transit proposals. But making buses free might weaken the rider advocacy that protects service quality.

4 min read EconomicsEconomics

Are stock returns normally distributed? Formal normality tests reject this assumption for most equity indices, with major implications for risk management.

2 min read Quantitative FinanceQuant

Apple's Illusion of Thinking paper found AI reasoning models collapse at high complexity. But critics argue the methodology, not the models, may be flawed.

2 min read AIAI

Kalshi's CFTC-regulated exchange now offers sports betting nationwide. If you can bet on oil futures, why not NFL touchdowns? The line is thinner than you think.

2 min read InvestingInvesting

LLMs excel at parsing market sentiment and writing reports, but finance demands audit trails and explainable decisions that black box models cannot provide.

1 min read AIAI

New NBER paper shows optimal Fed policy should partially accommodate tariff inflation, exposing a fault line in the dual mandate when prices and jobs conflict.

1 min read MacroMacro

UBS paper uses Transition Probability Tensors to bridge machine learning and arbitrage-free derivatives pricing, offering a faster alternative to Monte Carlo.

2 min read Quantitative FinanceQuant

Research shows passive investing makes markets more volatile as index fund growth amplifies each trade's price impact while active managers lag behind.

2 min read InvestingInvesting

Google released AlphaFold 3 for free, predicting molecular interactions beyond proteins. But is this generosity or a cloud platform play to own drug discovery?

1 min read MedicineMedicine

Statistical analysis of 20,000 crash game rounds verifies the 97% RTP claim. But 179 rounds per hour means expected losses exceed 500% of wagers hourly.

4 min read Quantitative FinanceQuant

Training RoBERTa to predict Hacker News success revealed temporal leakage inflating metrics. How temporal splits, calibration, and regularization fix it.

5 min read AIAI

Analysis of 32,000 HN posts reveals 65% negative sentiment correlates with 27% higher engagement. Six-model comparison, power-law distributions, full data.

2 min read AIAI

Build an open-source ML RSS reader with swipe interface. Uses MPNet embeddings and Thompson sampling for personalized feeds that escape the filter bubble.

4 min read AIAI

Build a privacy-focused newsletter with Python, Cloudflare Workers KV, and Resend API. Zero tracking, zero cost, full control. Open source code included.

4 min read TechTech

Cursor AI deployed YOURLS on Azure via SSH in 15 minutes: server config, MySQL, SSL, and a custom plugin. Full transcript and tutorial available.

2 min read TechTech

Build the right mental model for gradients with this PyTorch visualization tool. 2D surface plots with gradient vectors show the direction of steepest ascent.

1 min read TechTech

How I trained a YOLOv11 model to detect playing cards at 99.5% accuracy and built a real-time Monte Carlo blackjack odds calculator using computer vision.

6 min read TechTech

A hands-on project predicting postprandial glucose curves with XGBoost, Gaussian curve fitting, and 27 engineered features from CGM data. Code on GitHub.

6 min read TechTech

GPT-3.5 matched RavenPack's 41% returns in a sentiment analysis trading strategy using 2,072 news headlines. See the full backtest results and comparison.

6 min read AIAI

Built a CGM data analysis tool with Python to visualize Freestyle Libre 3 glucose data alongside nutrition, workouts, and sleep for endurance cycling.

3 min read TechTech

How I built a crypto mean reversion trading bot using PELT change point detection on Kraken, targeting altcoin price overreactions with automated execution.

3 min read InvestingInvesting

How I built Python portfolio optimization tools, tripled the Sharpe ratio from 0.65 to 1.68, and published the results as an academic paper on MPT.

2 min read InvestingInvesting

A Hugo blog tech stack with Cloudflare R2 image hosting, responsive WebP shortcodes, Workers AI social automation, and GitHub Pages CI/CD deployment.

4 min read TechTech