Gambling can be harmful and lead to significant losses. Participation is subject to local laws and age restrictions. Always gamble responsibly. Need help? Visit BeGambleAware.org

Crash games represent a category of online gambling where players place bets on an increasing multiplier that can ‘crash’ at any moment. The fundamental mechanic requires players to cash out before the crash occurs; successful cash-outs yield the bet amount multiplied by the current multiplier, while failure results in total loss of the wager.

The specific game I came across is a variant that employs an aircraft flight metaphor. Let’s call it Plane Game. What intrigued me wasn’t the game itself but that it said “provably fair” on the startup screen, which I assumed to be a typo at first. I stand corrected:

A provably fair gambling system uses cryptography to let players verify that each outcome was generated from fixed inputs, rather than chosen or altered by the operator after a bet is placed. The casino commits to a hidden “server seed” via a public hash, combines it with a player-controlled “client seed” and a per-bet nonce, and later reveals the server seed so anyone can recompute and confirm the result.

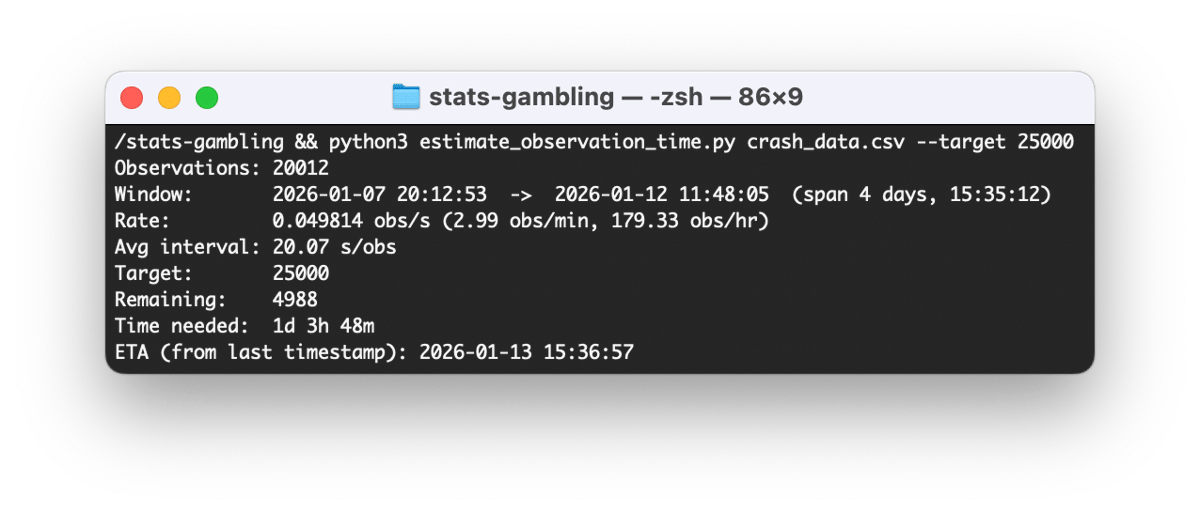

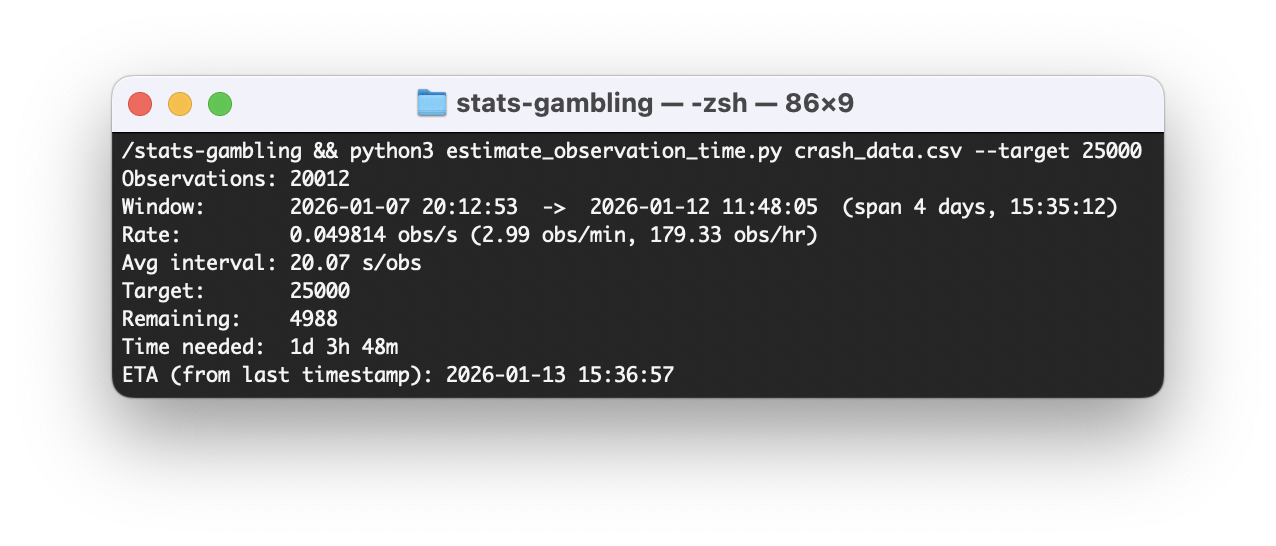

The stated Return-to-Player (RTP) of that specific game is 97%, implying a 3% house edge. After watching a few rounds, the perceived probability felt off. And if there’s something that gets my attention, it’s the combination of games and statistics. So I did what any reasonable person would do: I watched another 20,000 rounds over six days (112 hours total) and wrote a paper about it.

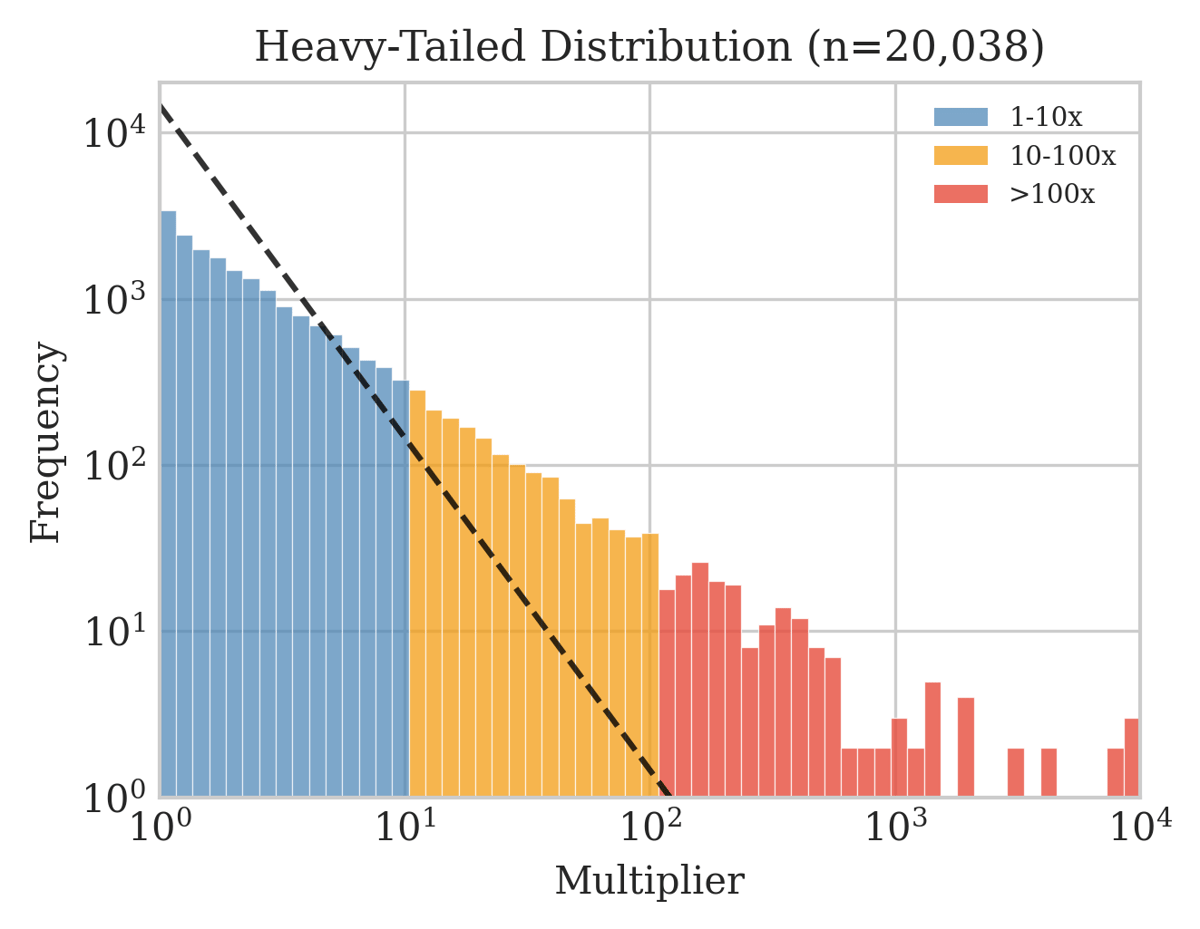

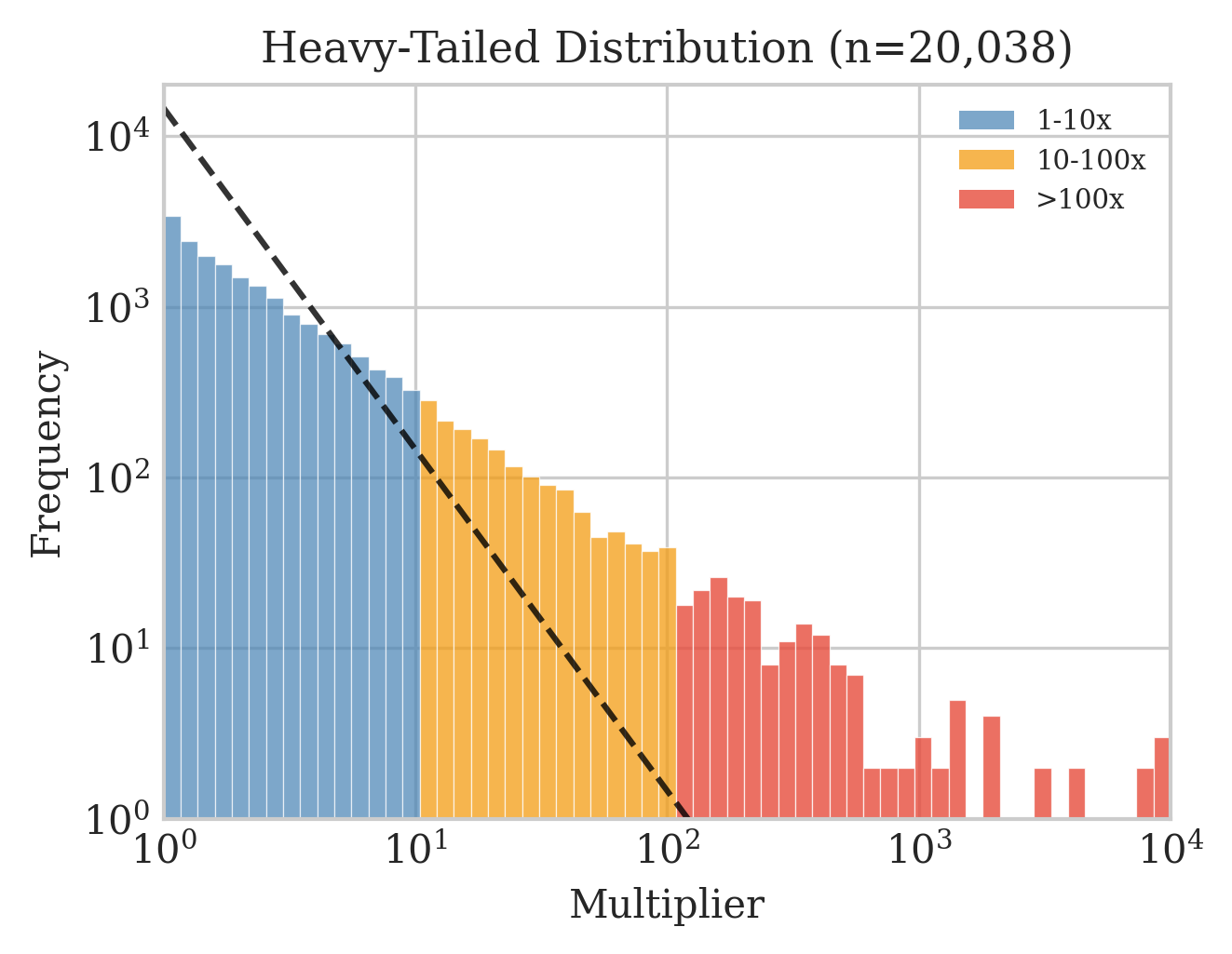

The distribution below shows the classic heavy tail: most rounds crash quickly at low multipliers, while rare events produce 100x or even 1000x payouts. The maximum I observed was 10,000x. This extreme variance creates the illusion of big wins just around the corner while the house edge operates relentlessly over time.

For a crash game with RTP = r (where 0 < r < 1), the crash multiplier M follows a specific probability distribution. The survival function is particularly relevant:

For a crash game with RTP = r (where 0 < r < 1), the crash multiplier M follows a specific probability distribution. The survival function is particularly relevant:

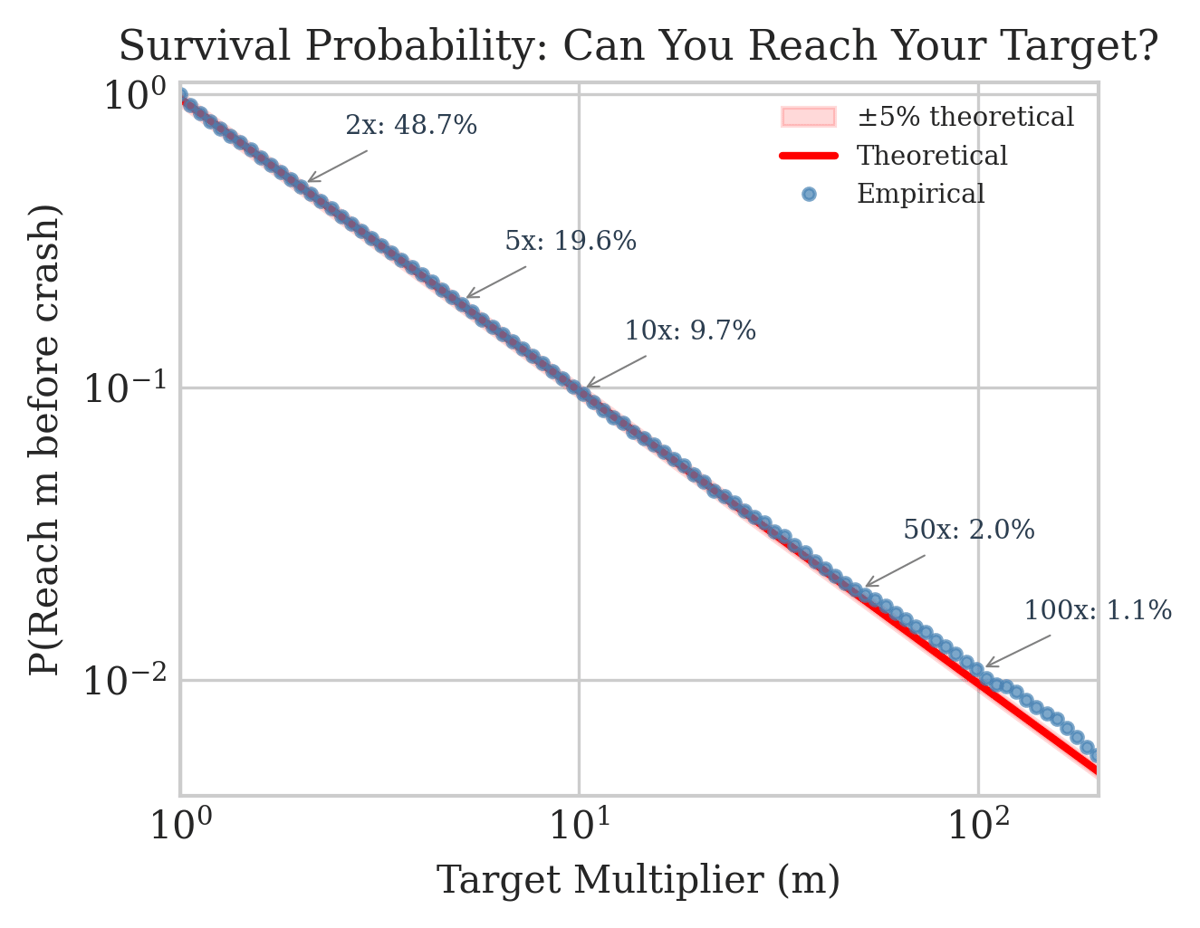

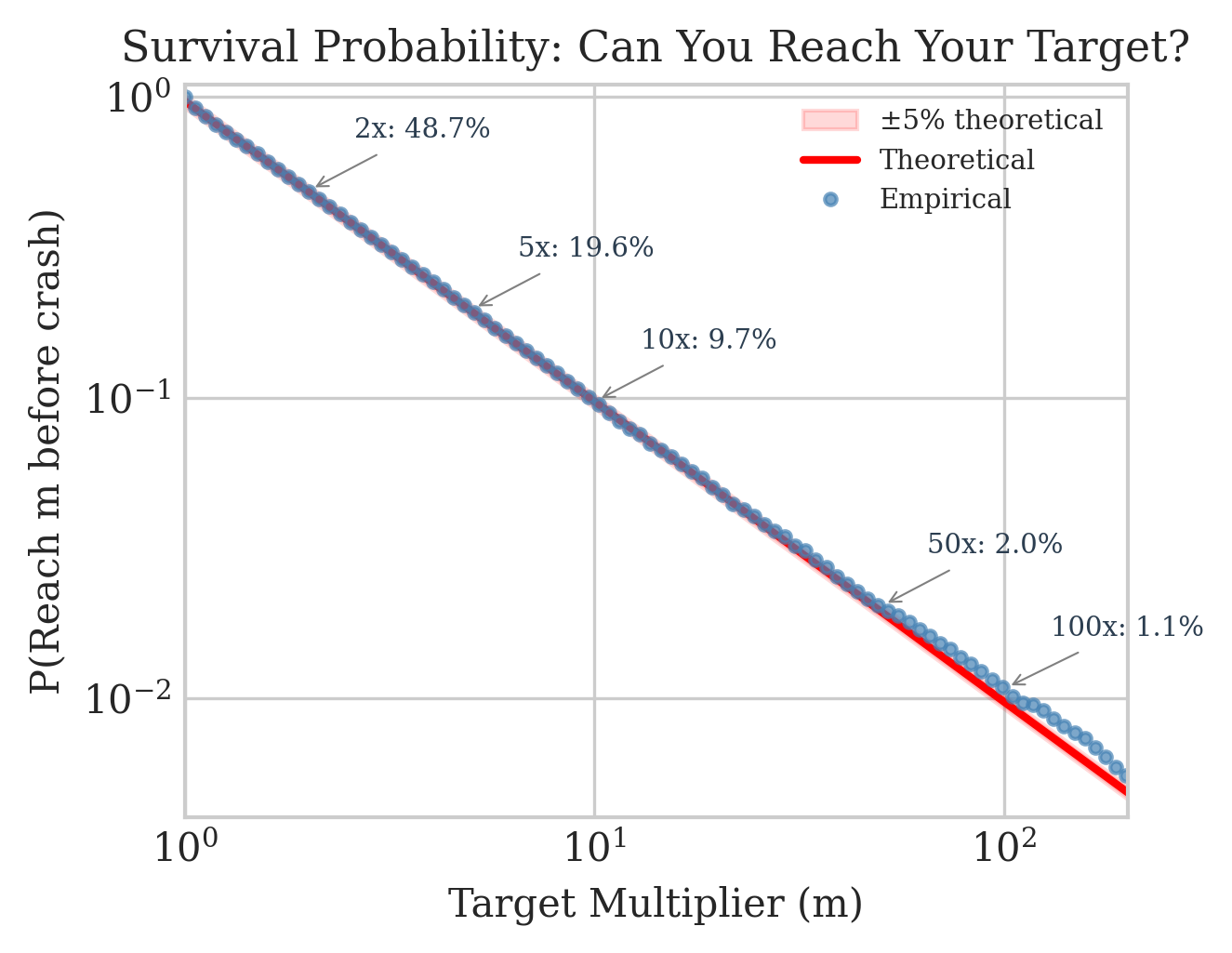

This means the probability of reaching at least multiplier m before crashing equals r/m. For any cash-out target, the expected value of a unit bet works out to:

$$E[\text{Profit}] = P(M \geq m) \times m - 1 = \frac{r}{m} \times m - 1 = r - 1 = -0.03$$This mathematical property makes crash games theoretically “strategy-proof” in expectation. No cash-out timing strategy should yield better long-term results than another.

The empirical data matches theory almost perfectly. A 2x target succeeds about 48.5% of the time. Aiming for 10x? That works only 9.7% of rounds. The close fit between my observations and the theoretical line confirms the stated 97% RTP.

The empirical data matches theory almost perfectly. A 2x target succeeds about 48.5% of the time. Aiming for 10x? That works only 9.7% of rounds. The close fit between my observations and the theoretical line confirms the stated 97% RTP.

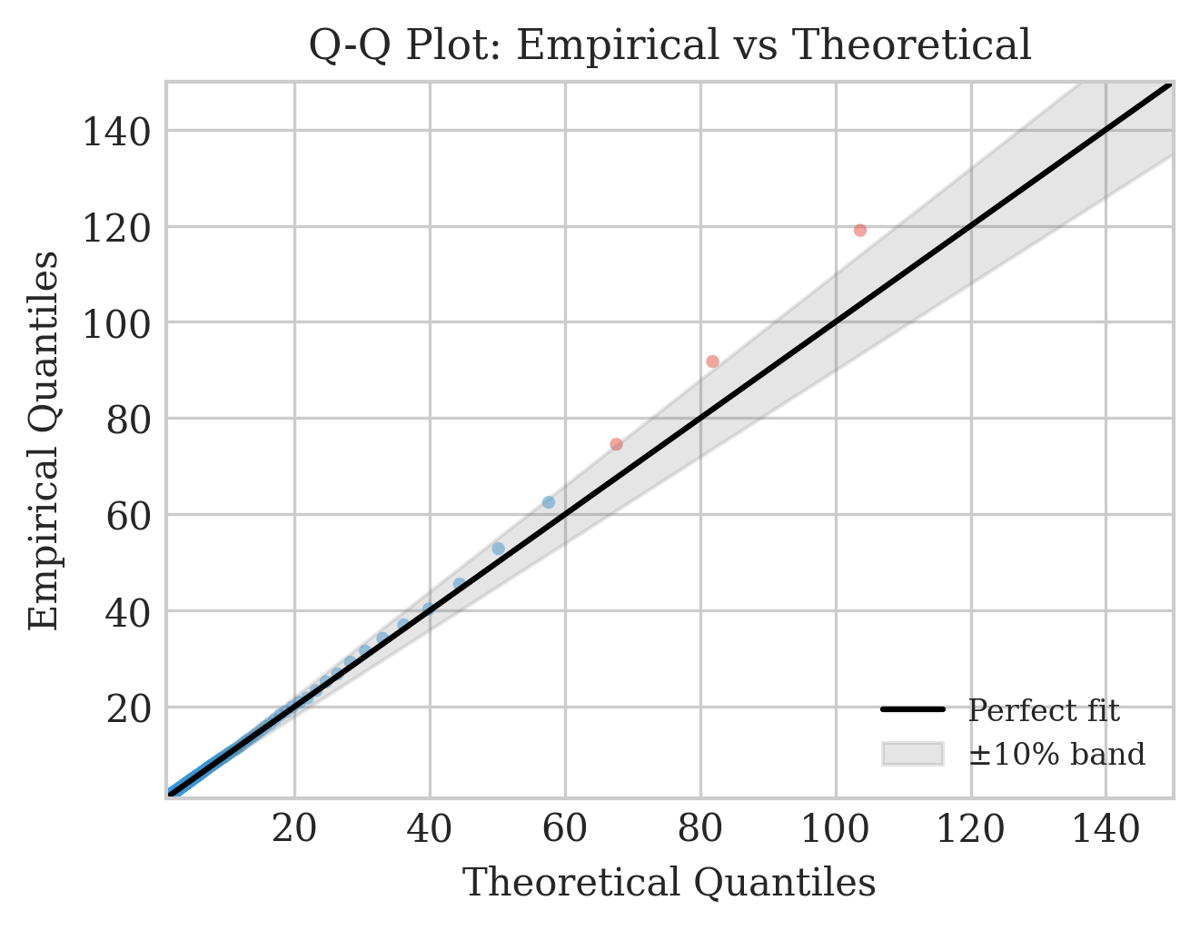

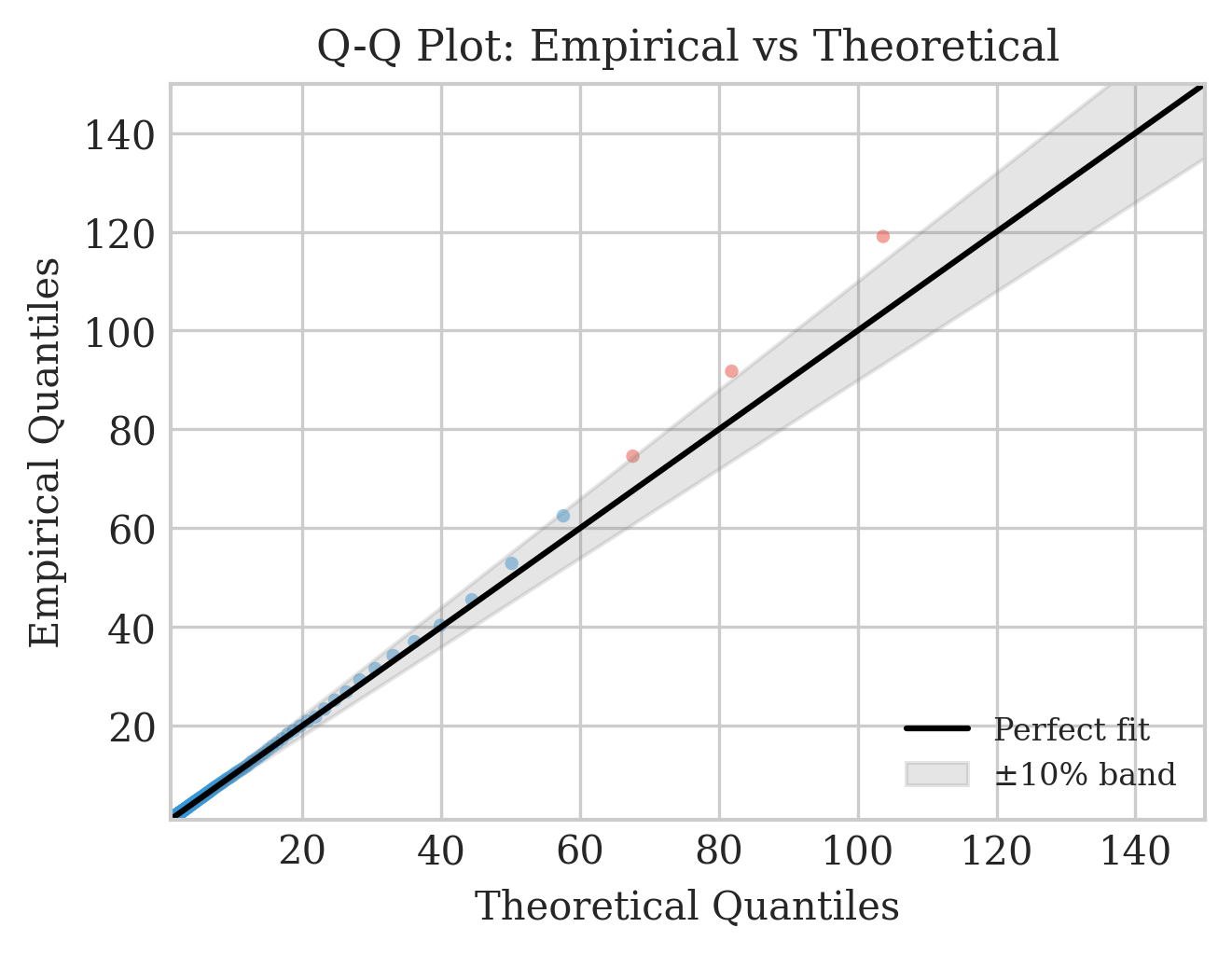

So is the game fair? My analysis says yes. Using three different statistical methods (log-log regression, maximum likelihood, and the Hill estimator), I estimated the probability density function exponent at α ≈ 1.98, within 2.2% of the theoretical value of 2.0. This contrasts with Wang and Pleimling’s 2019 research that found exponents of 1.4 to 1.9 for player cashout distributions. The key distinction: their deviations reflect player behavioral biases (probability weighting), not game manipulation. The random number generator produces fair outcomes.

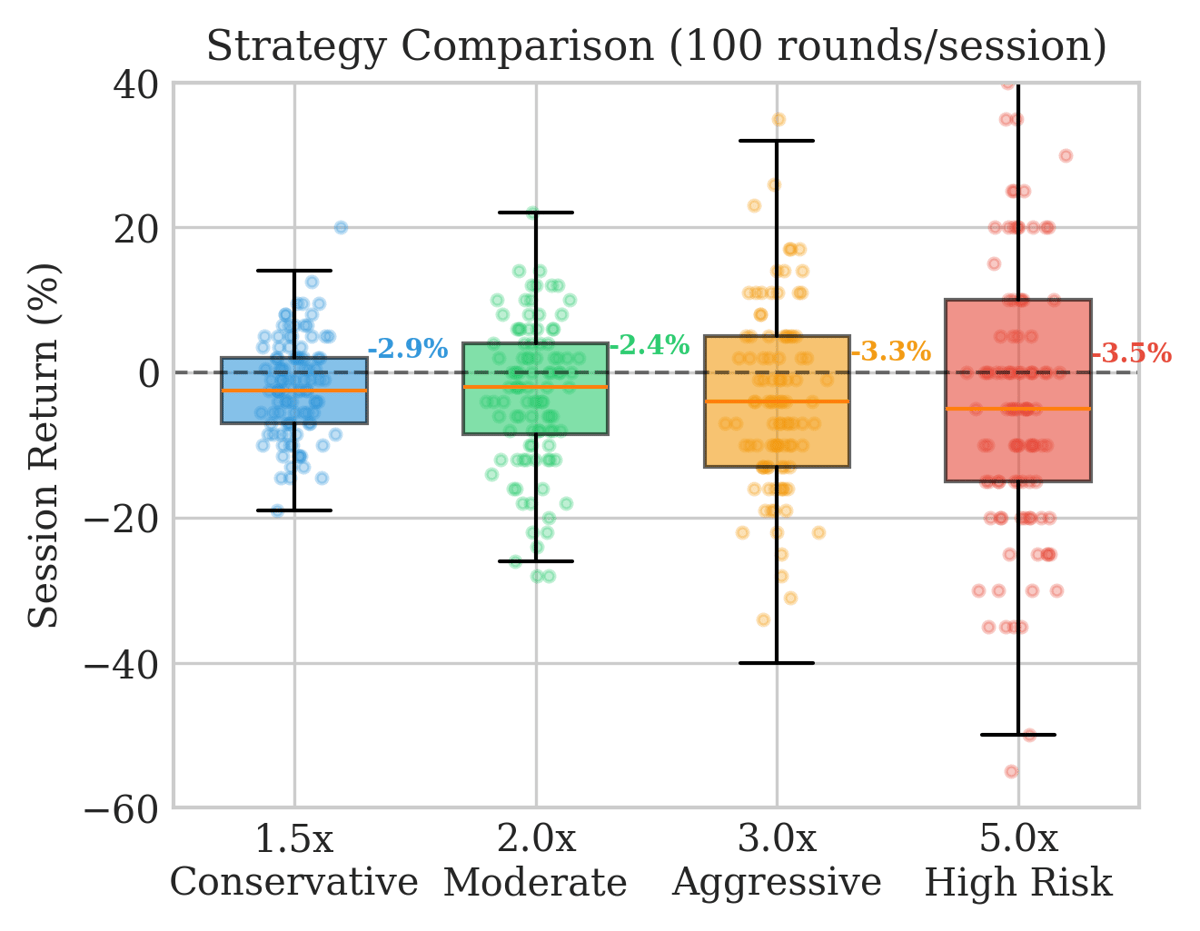

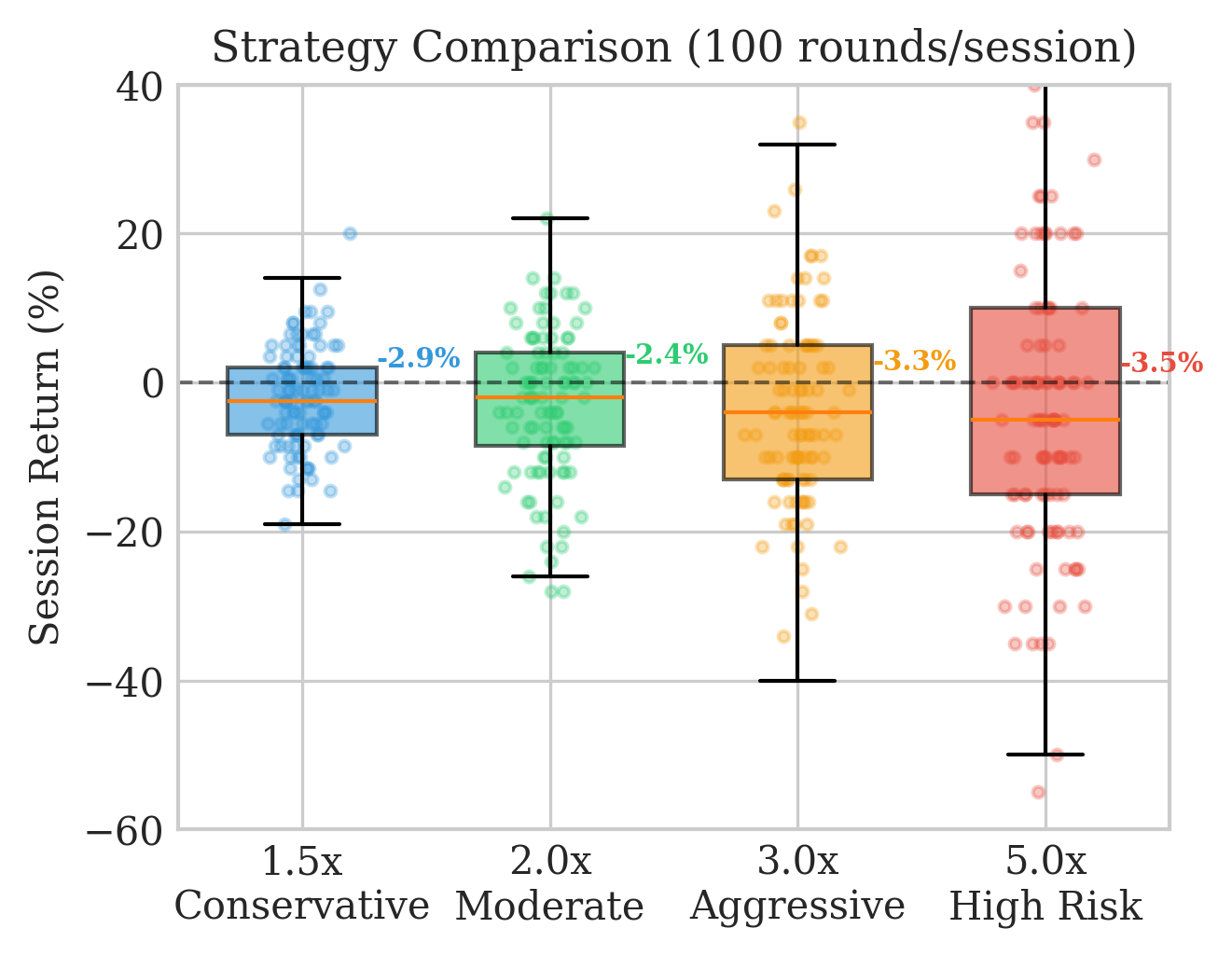

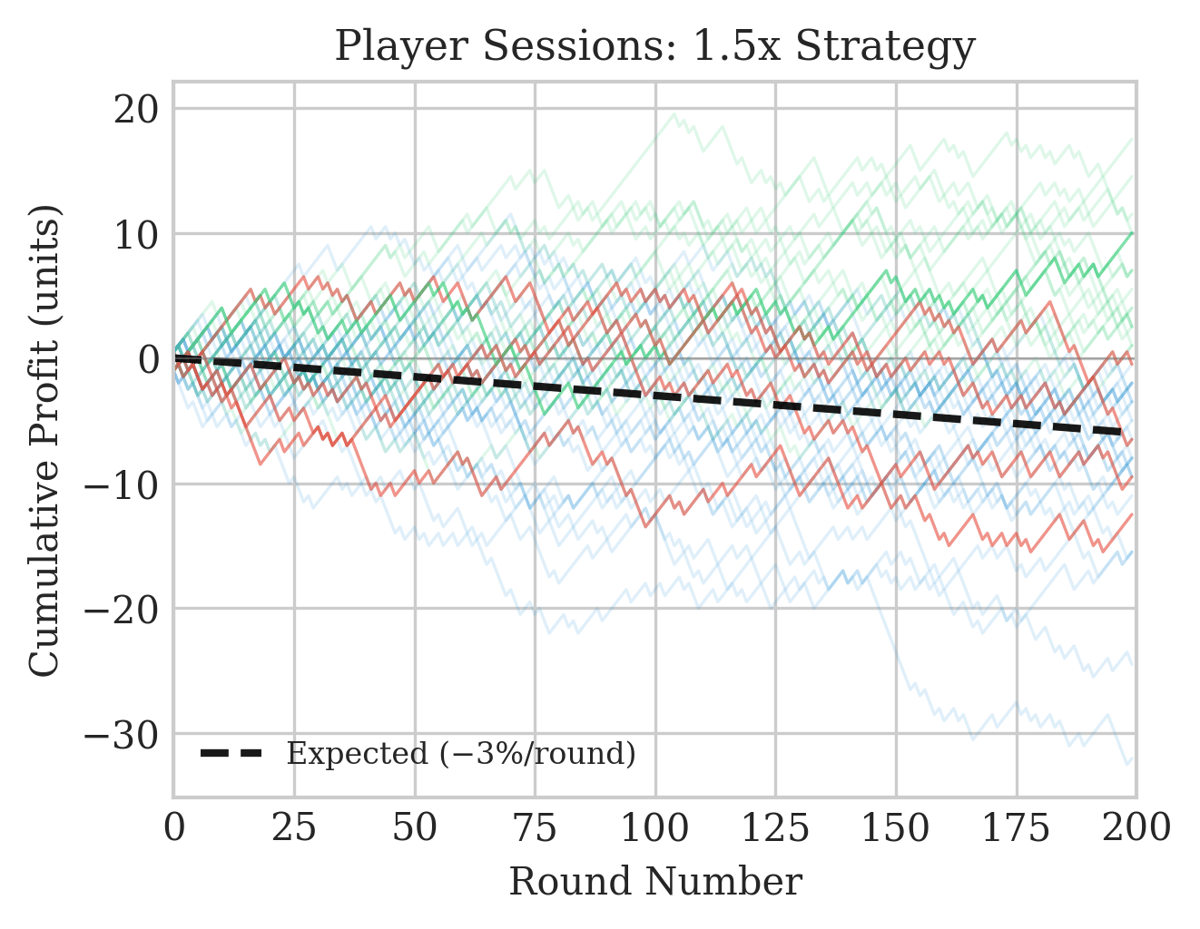

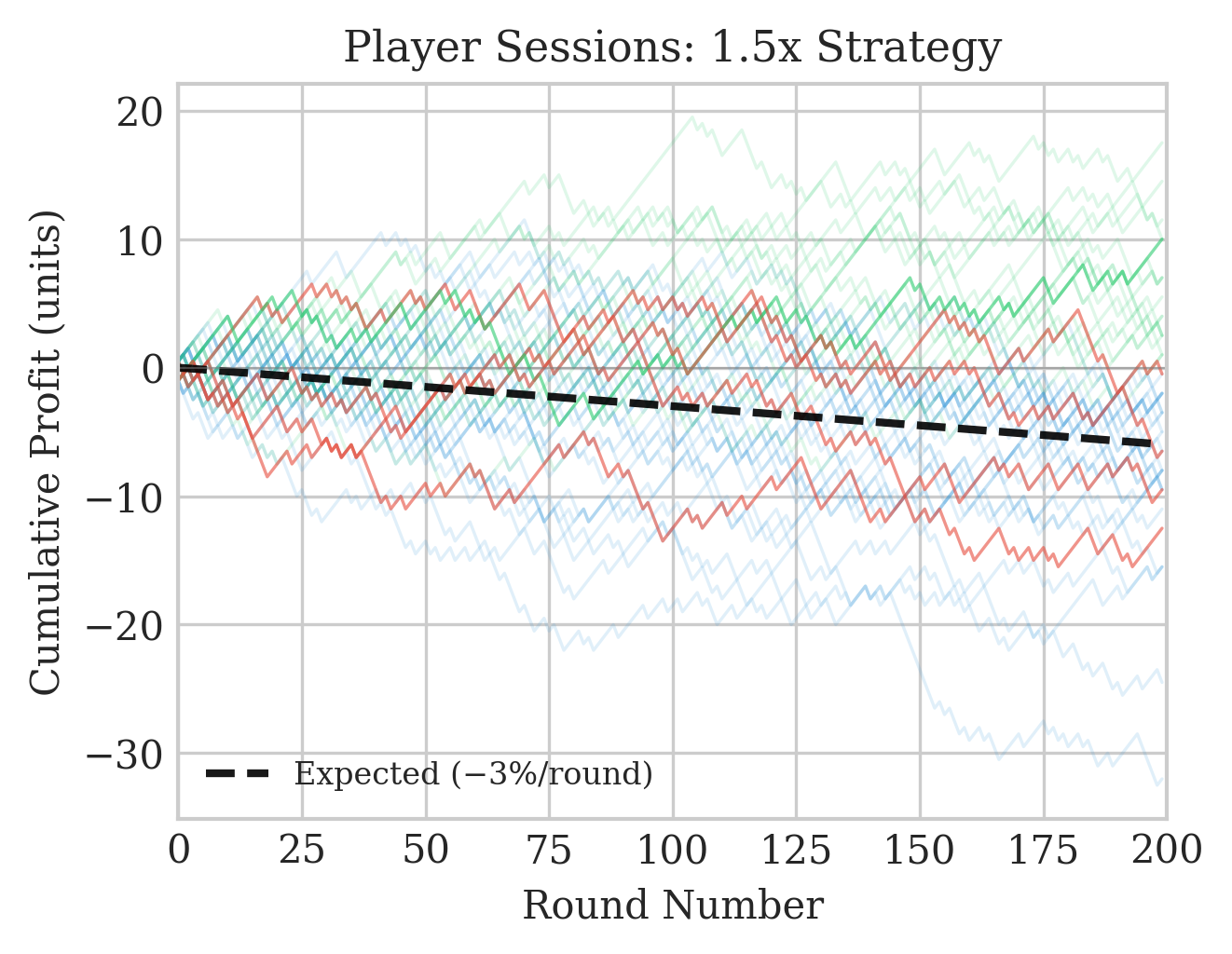

I then ran Monte Carlo simulations of 10,000 betting sessions under four different strategies: conservative 1.5x cashouts, moderate 2.0x, aggressive 3.0x, and high-risk 5.0x targets.

I then ran Monte Carlo simulations of 10,000 betting sessions under four different strategies: conservative 1.5x cashouts, moderate 2.0x, aggressive 3.0x, and high-risk 5.0x targets.

Every single strategy produces negative expected returns. The conservative approach has lower variance but still loses. The aggressive strategies lose faster with higher variance.

Every single strategy produces negative expected returns. The conservative approach has lower variance but still loses. The aggressive strategies lose faster with higher variance.

The consumer protection angle is what concerns me most. My data revealed 179 rounds per hour with 16-second median intervals. At that pace, with a 3% house edge per round, players face expected losses exceeding 500% of amounts wagered per hour of play. The manual cashout mechanic creates an illusion of control, masking the deterministic nature of losses.

The consumer protection angle is what concerns me most. My data revealed 179 rounds per hour with 16-second median intervals. At that pace, with a 3% house edge per round, players face expected losses exceeding 500% of amounts wagered per hour of play. The manual cashout mechanic creates an illusion of control, masking the deterministic nature of losses.

The game is provably fair in the cryptographic sense. The mathematics check out. But mathematical fairness doesn’t ensure consumer safety. The house always wins, and it wins fast.

The only winning strategy is not to play

The full paper preprint with methodology and statistical details is available on SSRN. Code and data are on GitHub.