Hyperscalers spent over $350 billion on AI infrastructure in 2025 alone, with projections exceeding $500 billion in 2026. The trillion-dollar question is not whether machines can reason, but whether anyone can afford to let them. Recommender systems sit at the center of this tension. Large Language Models promised to transform how Netflix suggests your next show or how Spotify curates your morning playlist. Instead, the industry has split into two parallel universes, divided not by capability but by cost.

On one side sits what engineers call the “classical stack”: matrix factorization, two-tower embedding models, and contextual bandits. These methods respond in microseconds, scale linearly with users, and run on nothing more complicated than dot products. A query costs a fraction of a cent. On the other side is the “agentic stack”: LLM-based reasoning engines that can handle requests like “find me a sci-fi movie that feels like Blade Runner but was made in the 90s.” This second approach consumes thousands of tokens per recommendation. The cost difference is not incremental; it is orders of magnitude.

The 2026 consensus is a hybrid architecture: use the cheap, fast models to retrieve a thousand candidates from millions, then invoke the expensive reasoning layer only for the final dozen items a user actually sees. This “funnel” pattern is the only way to make the economics work. The smartest model is reserved for the fewest items.

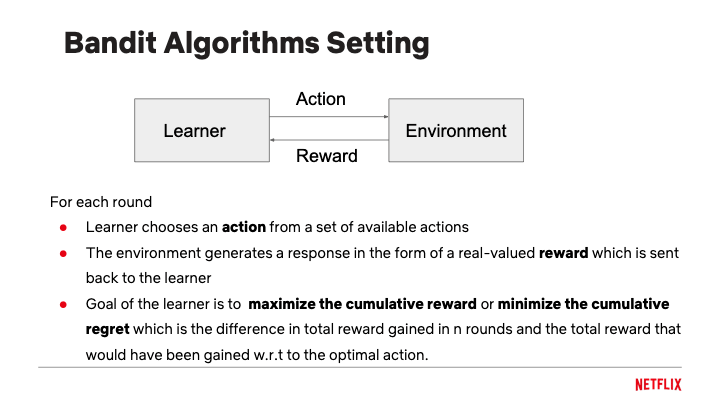

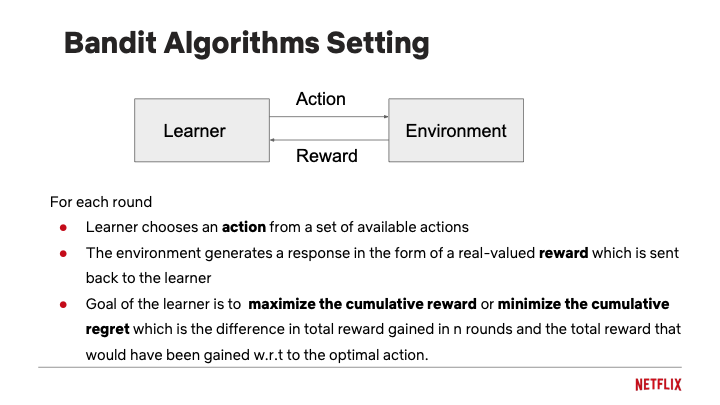

What makes this work in practice goes back to a formalism from 1933: the multi-armed bandit. Imagine a gambler facing a row of slot machines, each with an unknown payout rate. She wants to maximize her winnings over a night of play. If she always pulls the arm with the highest observed payout, she might miss a better machine she never tried. If she explores too much, she wastes money on losers. The mathematics of this tradeoff define regret:

$$ R(T) = \mu^* \cdot T - \sum_{t=1}^{T} \mu(a_t) $$Here μ* is the best possible average reward, and μ(aₜ) is the reward from whatever arm she actually pulled at time t. Total regret is how much she left on the table by not knowing the optimal choice in advance.

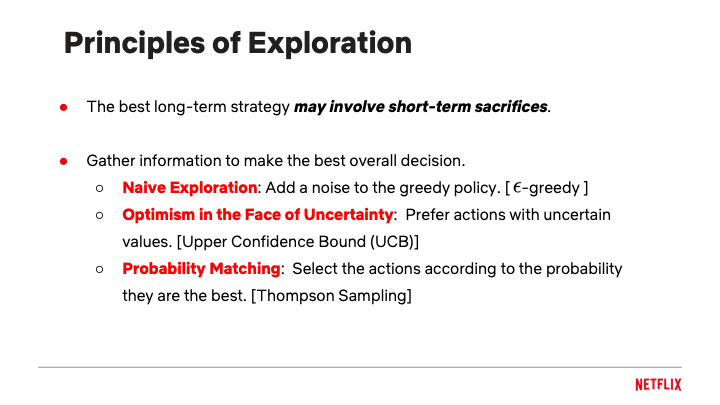

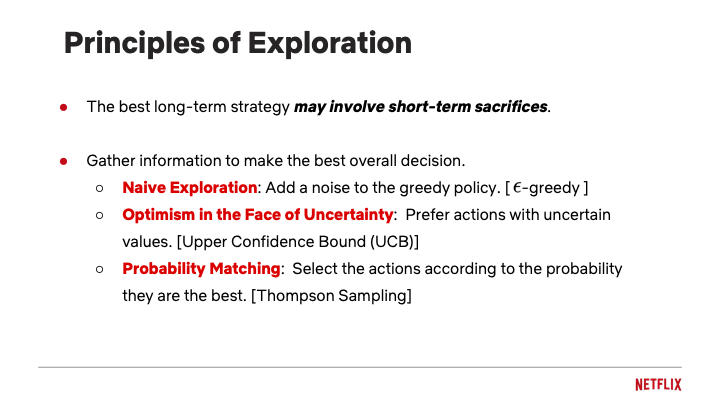

The three main exploration strategies each take a different approach: epsilon-greedy adds random noise to avoid getting stuck; Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) prefers actions with uncertain values; Thompson Sampling selects actions according to the probability they are optimal.

The three main exploration strategies each take a different approach: epsilon-greedy adds random noise to avoid getting stuck; Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) prefers actions with uncertain values; Thompson Sampling selects actions according to the probability they are optimal.

Every recommendation you see on Netflix’s homepage is the output of an algorithm trying to minimize exactly this quantity, whether it realizes it or not.

Every recommendation you see on Netflix’s homepage is the output of an algorithm trying to minimize exactly this quantity, whether it realizes it or not.

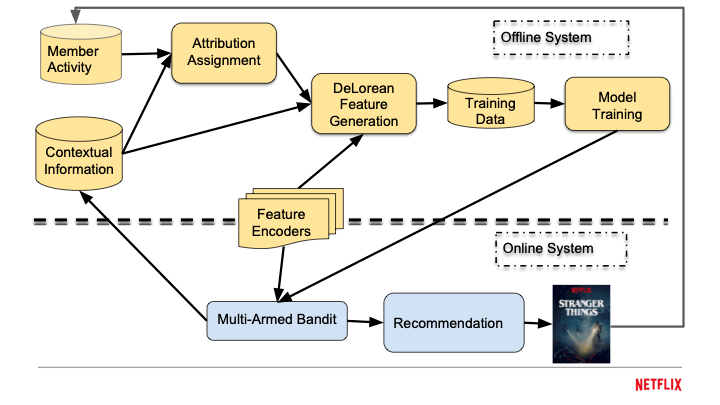

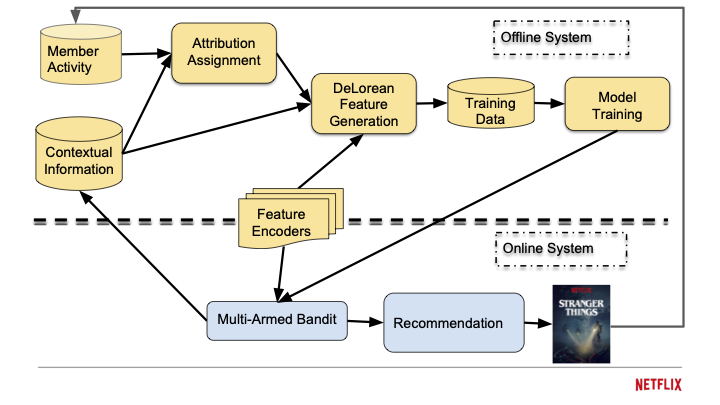

Netflix runs this optimization across three computation layers. Offline systems crunch terabytes of viewing history to train the models, a process that takes hours and happens on a schedule. Nearline systems update user embeddings seconds after a click, keeping the recommendations fresh without the cost of full retraining. Online systems respond to each page load in milliseconds, combining the precomputed signals with real-time context. The architecture is a latency-cost tradeoff: deep analysis happens in batch, while the user-facing layer stays fast.

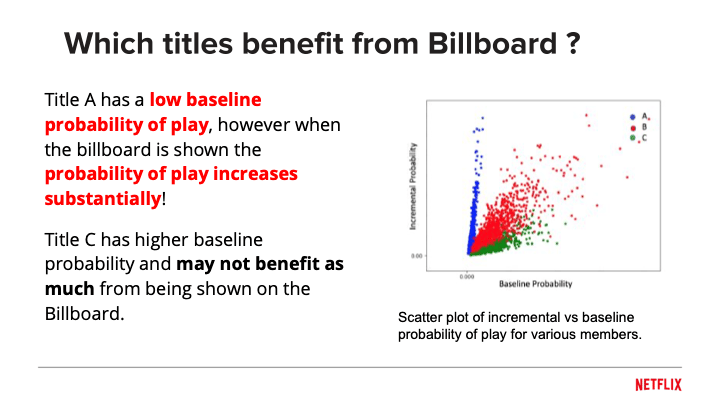

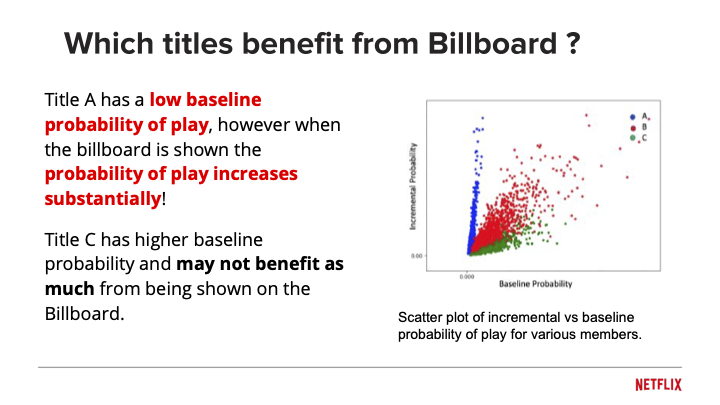

What Netflix learned from a decade of experimentation is counterintuitive. The goal is not to recommend what users will definitely watch, but what they would not have found on their own. They call this “incrementality.” A greedy algorithm that always surfaces the highest-probability titles just confirms what users already knew. A better approach is to measure the causal effect of the recommendation: how much does showing this thumbnail increase the probability of a play compared to not showing it? Some titles have low baseline interest but high incrementality. Those are the ones worth featuring.

What Netflix learned from a decade of experimentation is counterintuitive. The goal is not to recommend what users will definitely watch, but what they would not have found on their own. They call this “incrementality.” A greedy algorithm that always surfaces the highest-probability titles just confirms what users already knew. A better approach is to measure the causal effect of the recommendation: how much does showing this thumbnail increase the probability of a play compared to not showing it? Some titles have low baseline interest but high incrementality. Those are the ones worth featuring.

Spotify takes a different approach to the same problem. Their “AI DJ” feature uses what engineers internally call the “agentic router.” When you ask for “music for a rainy reading session in 1990s Seattle,” the router decides whether to invoke the expensive LLM reasoning layer or just fall back to keyword matching. Complex queries get the big model; simple ones get the fast path. This router is the economic governor of the entire system.

Spotify takes a different approach to the same problem. Their “AI DJ” feature uses what engineers internally call the “agentic router.” When you ask for “music for a rainy reading session in 1990s Seattle,” the router decides whether to invoke the expensive LLM reasoning layer or just fall back to keyword matching. Complex queries get the big model; simple ones get the fast path. This router is the economic governor of the entire system.

Not everyone is convinced the algorithms are making us better off. My own analysis of social media success prediction found that sophisticated language models often just memorize temporal patterns rather than learning what actually makes content good. They learn the news cycle, not the news.

The risk is that we build systems technically brilliant but experientially hollow, engineering away the serendipity that made discovery meaningful in the first place. The recommender is becoming a curator, and the curator is becoming an agent. The open question for 2026 is whether we want to be the curators of our own lives, or merely consumers of an optimized feed.

Slides courtesy of “A Multi-Armed Bandit Framework for Recommendations at Netflix” by Jaya Kawale, Netflix.