Bitcoin’s security model rests on one assumption: attacking the network costs more than any attacker could gain. A 2024 paper by Farokhnia and Goharshady does the math on this assumption and finds it wanting.

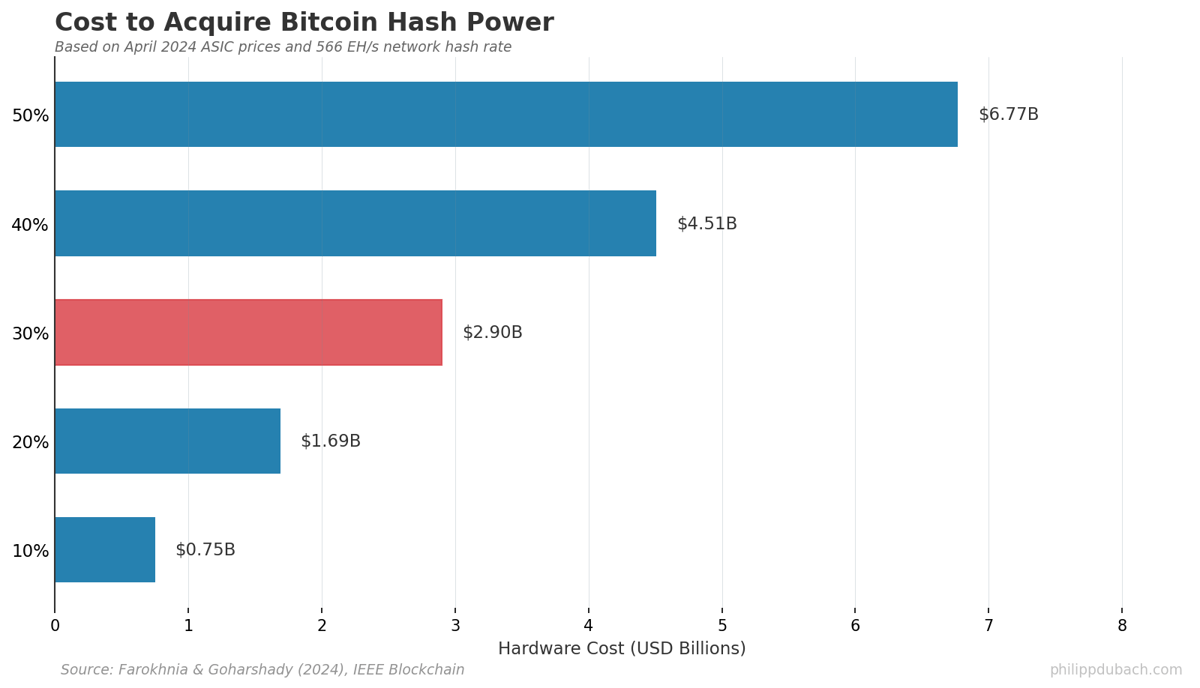

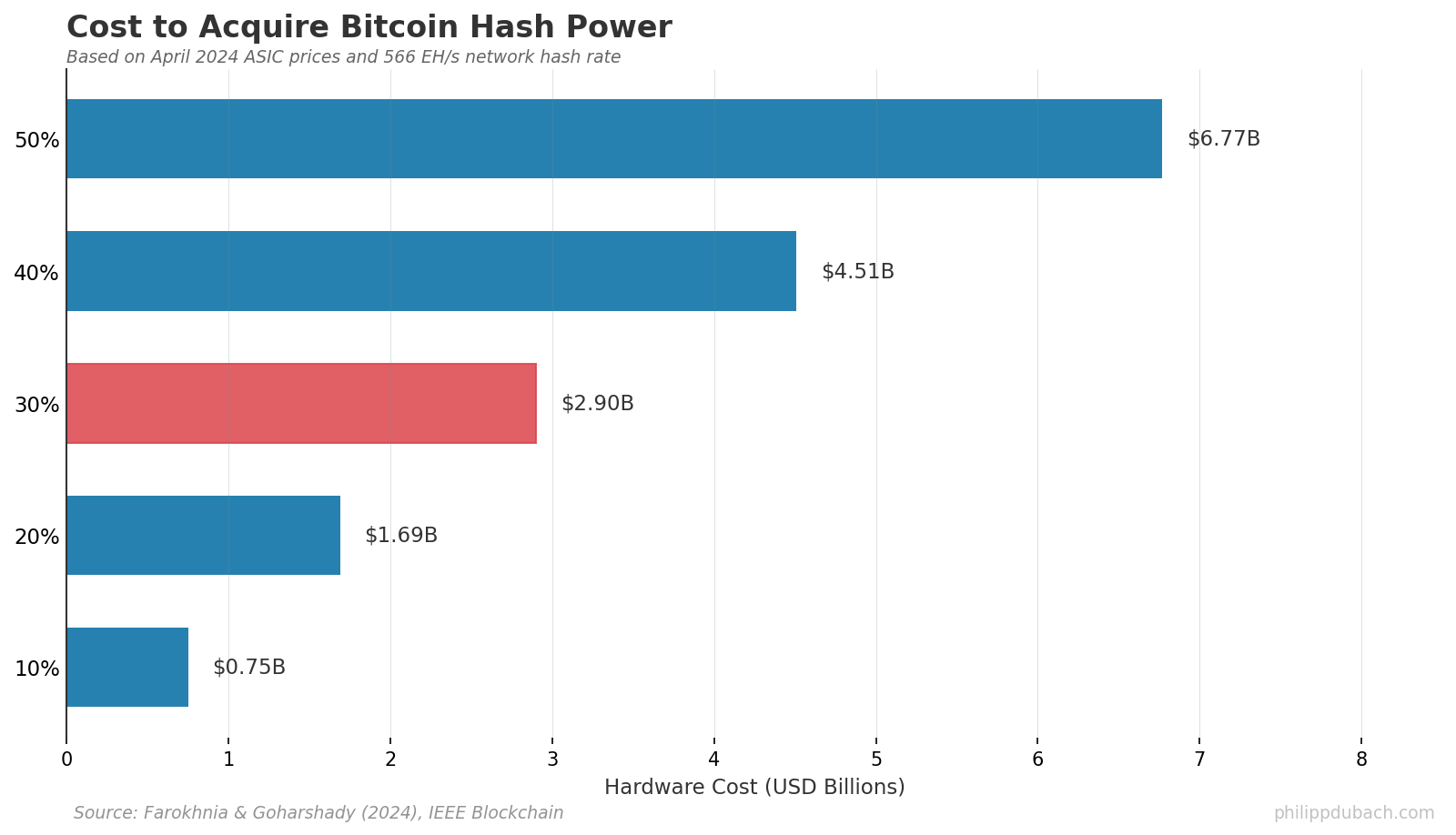

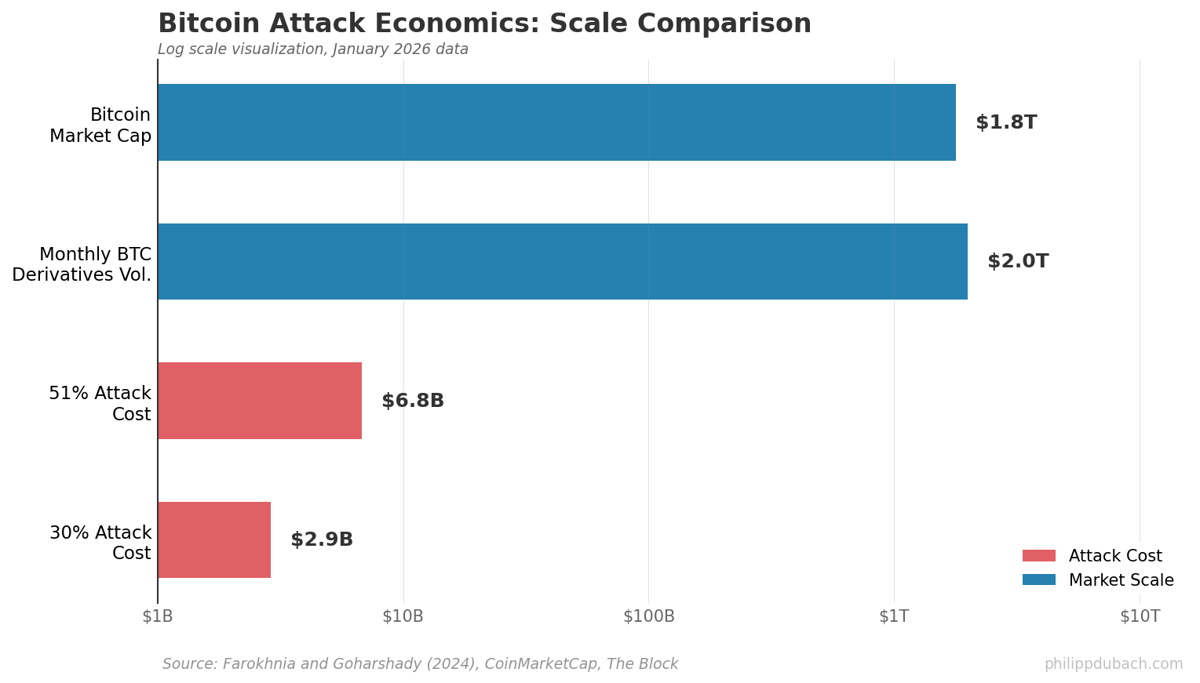

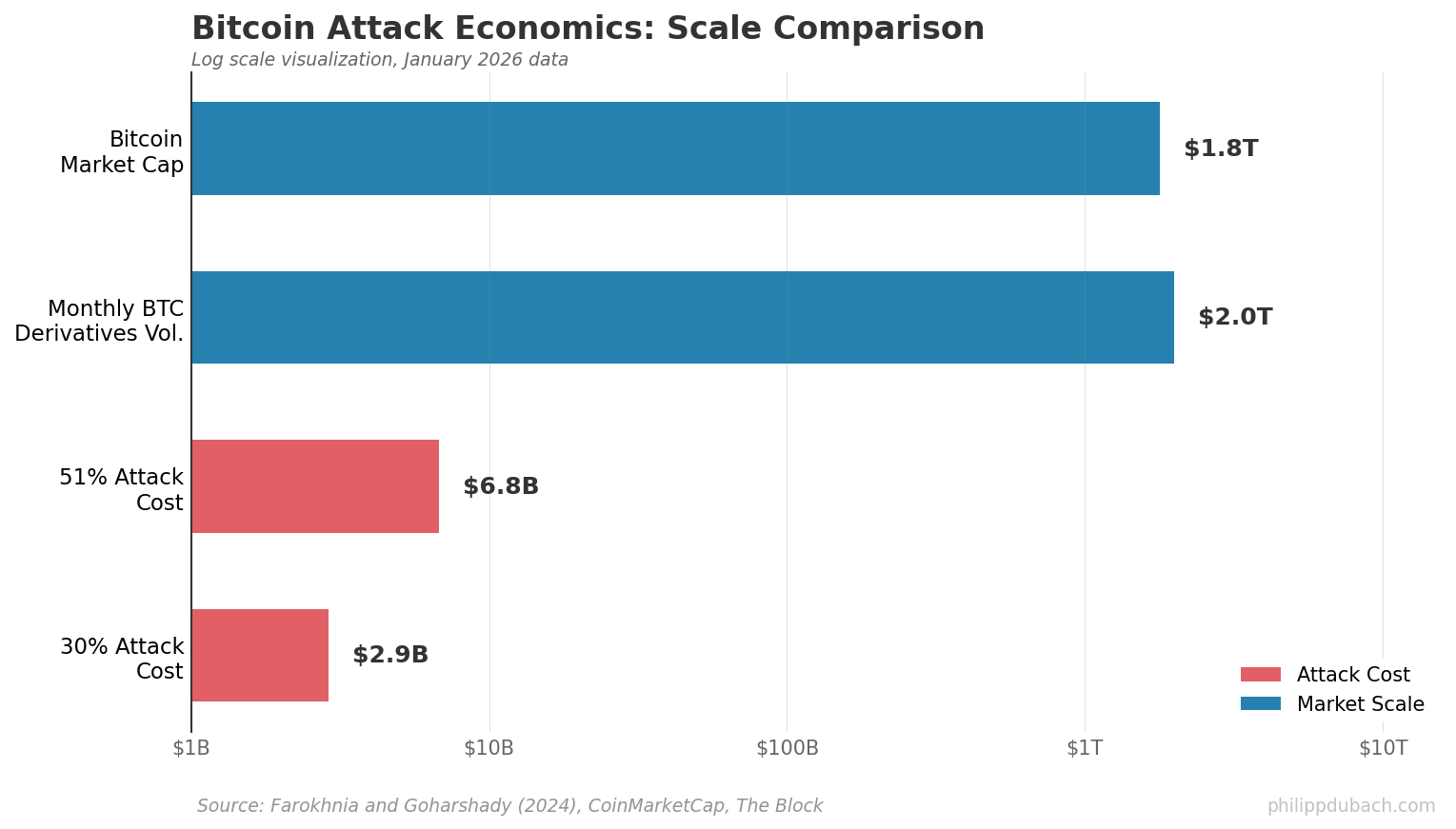

For roughly $6.77 billion in hardware, an attacker could control over 50% of Bitcoin’s hash rate. With 30% of hash power, success probability exceeds 95% within 34 days at a cost of about $2.9 billion.

These are large absolute numbers, but relatively small: Bitcoin’s $1.78 trillion market cap and the monthly derivatives volume that now regularly exceeds $2 trillion on unregulated exchanges alone. The attack pays for itself if you short Bitcoin before crashing its price.

The paper challenges three assumptions the crypto community has treated as fact. (1) That you need 51% of hash power to attack successfully. Not true. With 30%, you have high probability of reverting six blocks, enough to shatter the six-confirmation finality standard most practitioners rely on. (2) Acquiring majority hash power is prohibitively expensive. It is expensive but represents less than 0.5% of Bitcoin’s market cap. (3) miners have no incentive to attack since they depend on BTC-denominated rewards. This ignores derivatives entirely.

The paper challenges three assumptions the crypto community has treated as fact. (1) That you need 51% of hash power to attack successfully. Not true. With 30%, you have high probability of reverting six blocks, enough to shatter the six-confirmation finality standard most practitioners rely on. (2) Acquiring majority hash power is prohibitively expensive. It is expensive but represents less than 0.5% of Bitcoin’s market cap. (3) miners have no incentive to attack since they depend on BTC-denominated rewards. This ignores derivatives entirely.

In simple terms an attack would work like this: An attacker acquires put options or other shorting instruments on Bitcoin. They then use their hash power to mine secretly, building an alternative chain. When their chain exceeds the public chain in length, they publish it. The network switches to the longer chain. Transactions in the replaced blocks get reverted. Price crashes. The short position prints money.

David Rosenthal, writing on his blog, offers a detailed skeptic’s view of whether this attack is actually feasible. His analysis is worth reading because he identifies practical obstacles the paper’s theoretical framework glosses over. Acquiring 43% of the pre-attack hash rate means buying roughly two years of Bitmain’s production capacity beyond what’s needed to replace obsolete equipment. The purchase would be noticed. Power requirements approach 9.5 gigawatts, roughly double what Meta’s planned Louisiana 5GW data center will need by 2030. That power doesn’t (yet) exist in deployable form.

The short position presents its own problems. Patrick McKenzie’s explainer on perpetual futures describes how crypto derivatives actually work: frequent settlements, margin requirements, liquidation risk. A leveraged short held for 34 days has high probability of getting liquidated before the attack succeeds, given Bitcoin’s volatility. In nine of twelve months in 2025, an initial 10X leveraged short would have been liquidated within the month. Even if the attack succeeds, the resulting crash would likely trigger automatic deleveraging, reducing winnings precisely when they should be largest.

An insider attack looks more plausible on paper. A large mining pool already controls the hash rate. The October 2025 liquidation event on crypto exchanges saw $19 billion in forced liquidations. This demonstrates both the volatility of the market and its capacity to absorb large directional moves. But an insider who stops contributing to the public chain for weeks becomes visible. The hash rate is public data. A 30% drop would trigger immediate investigation.

The paper’s contribution, in my opinion, is making explicit what the derivatives market implies: Bitcoin’s security depends not just on proof-of-work economics but on the assumption that attackers cannot profit from price crashes. That assumption gets weaker as the derivatives market grows. Monthly Bitcoin futures volume on unregulated exchanges has exceeded $2 trillion in recent months. The paper’s calculations used April 2024 data. Since then, Bitcoin’s hash rate has roughly doubled to around 1,100 EH/s, increasing attack costs proportionally. But derivatives volumes have grown too.

The next halving arrives in April 2028. Mining rewards drop to 1.5625 BTC per block. Miners whose equipment is fully depreciated might view an attack as an exit strategy, particularly if they can monetize it through derivatives. Some large miners are already pivoting to AI data center hosting, suggesting they see diminishing returns from mining alone. Core Scientific plans to exit Bitcoin mining entirely by 2028.

The next halving arrives in April 2028. Mining rewards drop to 1.5625 BTC per block. Miners whose equipment is fully depreciated might view an attack as an exit strategy, particularly if they can monetize it through derivatives. Some large miners are already pivoting to AI data center hosting, suggesting they see diminishing returns from mining alone. Core Scientific plans to exit Bitcoin mining entirely by 2028.

What actually prevents this attack? Probably the practical difficulties Rosenthal identifies rather than any fundamental economic barrier. The market should price these risks but appears not to. Bitcoin trades as if 51% attacks are theoretical rather than economically viable. That may remain true as long as practical obstacles hold.