The defensible asset in enterprise AI is not the model. It’s the organizational world model.

Every major compute era decomposes into specialized layers with different winners at each level. Cloud split into IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS. The modern data stack split into ingestion, warehousing, transformation, and BI. Each time, specialists beat the generalists because the layers have fundamentally different economics: different rates of change, different capital requirements, different sources of lock-in.

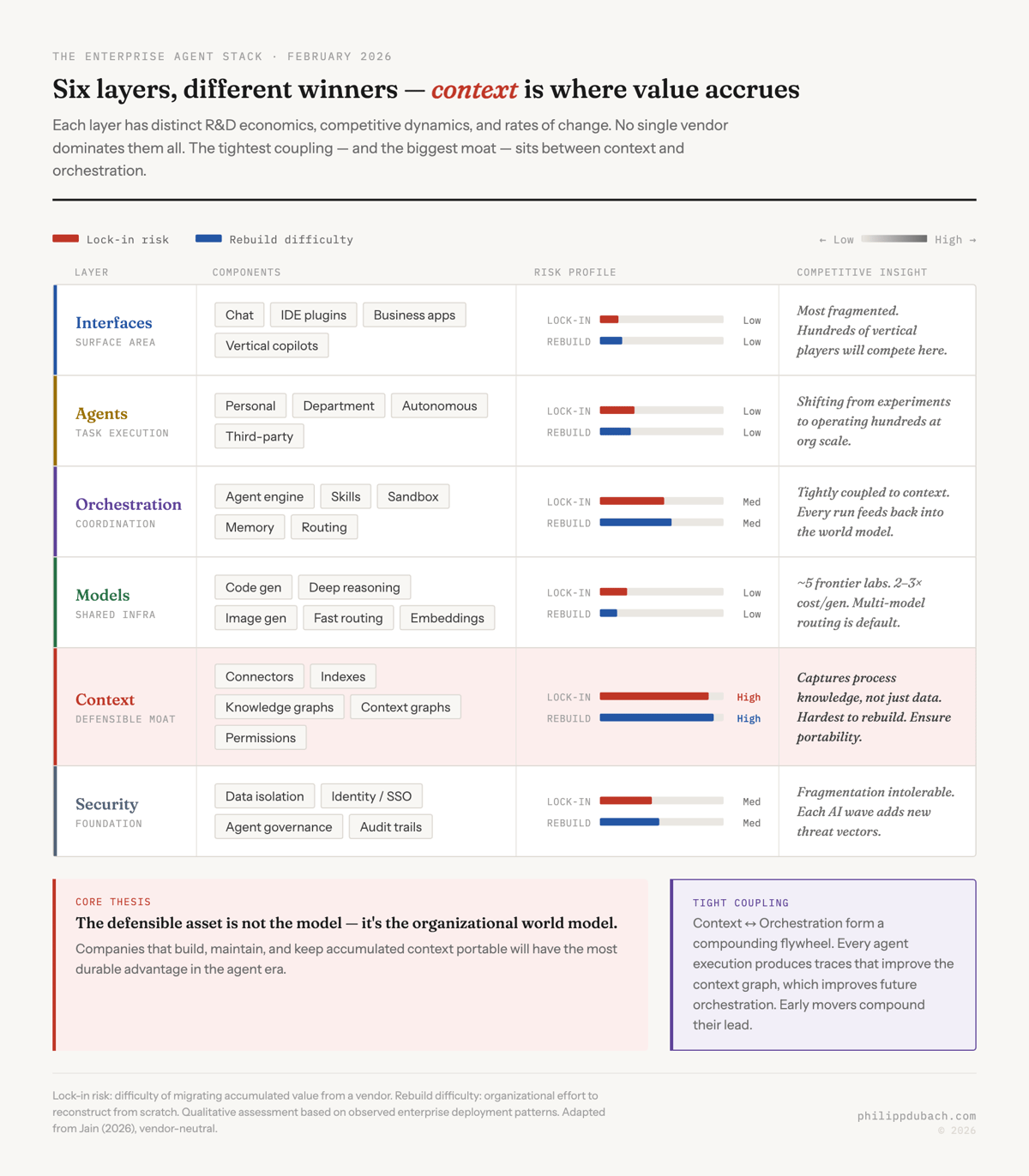

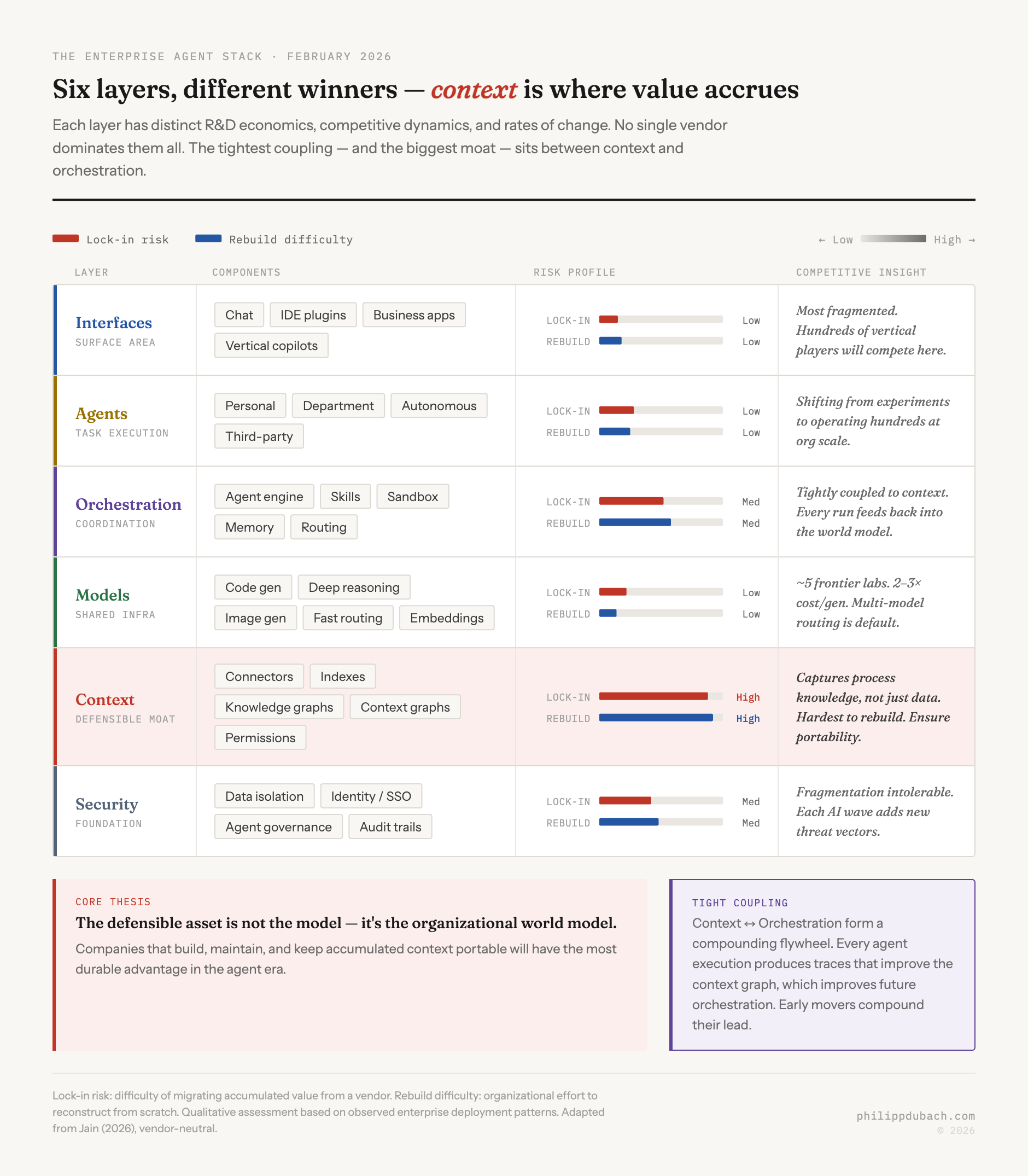

The enterprise AI agent stack is doing the same thing right now. Arvind Jain, the CEO of Glean, recently published a structural analysis of the emerging enterprise agent architecture that crystallized something I’d been thinking about. His framing describes a stack decomposing into six layers (security, context, models, orchestration, agents, and interfaces) with different defensibility profiles at each level. Glean sits in the context layer so the usual positioning caveats apply, but the structural argument is sound regardless of who makes it.

I want to take it further. There are three claims embedded in this agentic AI architecture that I think are underappreciated, and together they form a thesis about where durable advantage actually accrues in enterprise AI.

I. Models are converging toward shared infrastructure

The model layer is the one most people obsess over, and it’s also the one converging fastest toward commodity economics. Training costs scale roughly 2.4x per year, with current frontier runs costing hundreds of millions and billion-dollar training runs already underway, according to Anthropic’s Dario Amodei. Only a handful of organizations on Earth can operate at this scale: OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic, Meta, and a few others including xAI and Mistral. This is textbook capital-intensive infrastructure, structurally identical to semiconductor fabs or cloud hyperscalers. The logical conclusion: foundation models become shared utilities, not enterprise moats.

The industry has already internalized this. 37% of enterprises now use five or more models in production, up from 29% the prior year. Different tasks demand different models: Claude for code and tool use, GPT for extended reasoning, Gemini Flash for low-latency routing, specialized models for image generation and embeddings. Betting your enterprise stack on a single model provider is the new version of single-cloud risk. Open standards like Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol, now hosted by the Linux Foundation with 97 million monthly SDK downloads, and Google’s Agent-to-Agent protocol are making this multi-model enterprise AI architecture practical.

If models are infrastructure, the differentiation question moves up the stack. And that’s where it gets interesting.

II. The enterprise AI context layer has two depths, and most people only see the first

This is the part of the thesis I find most intellectually compelling, and where I think the conventional understanding falls short.

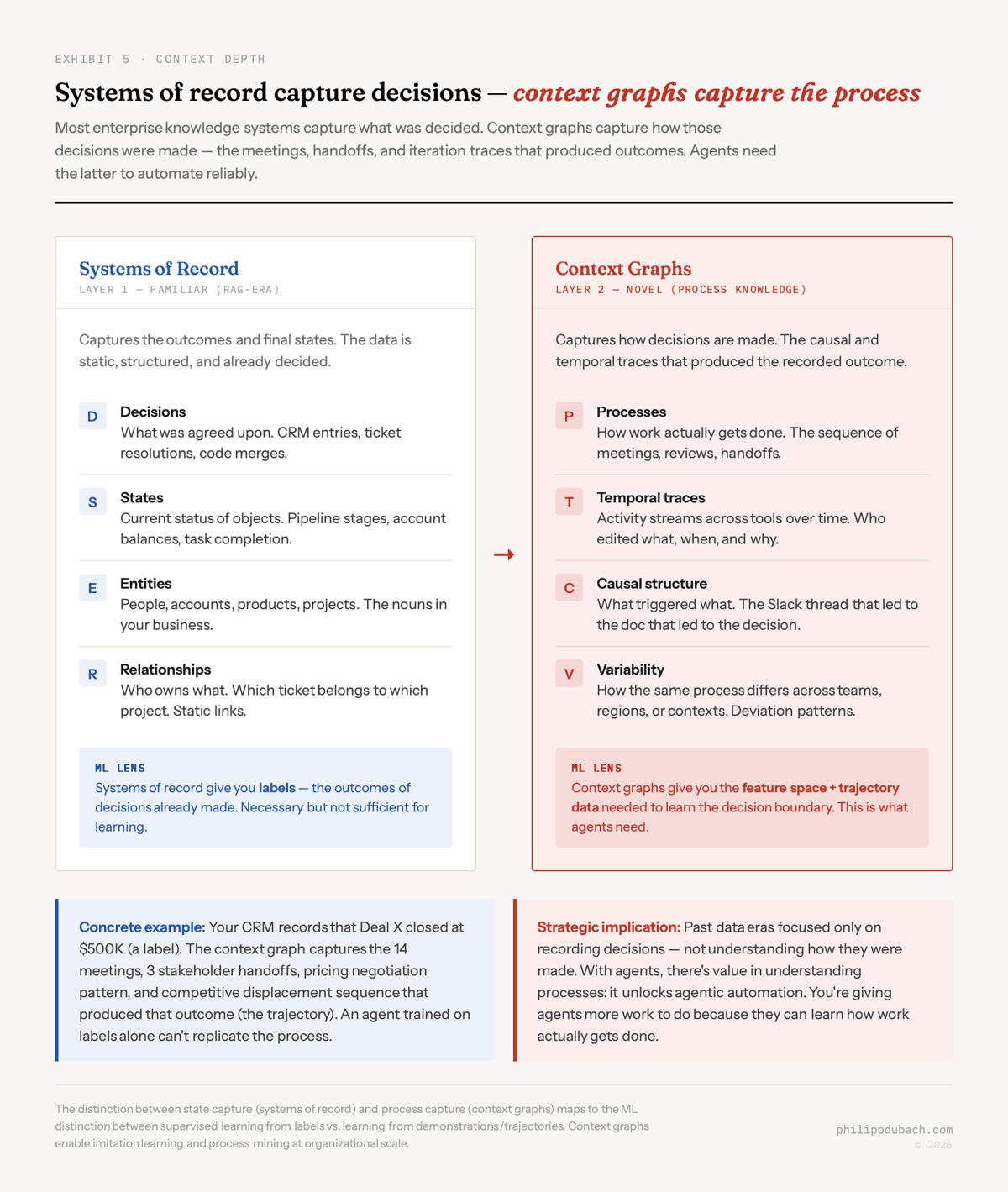

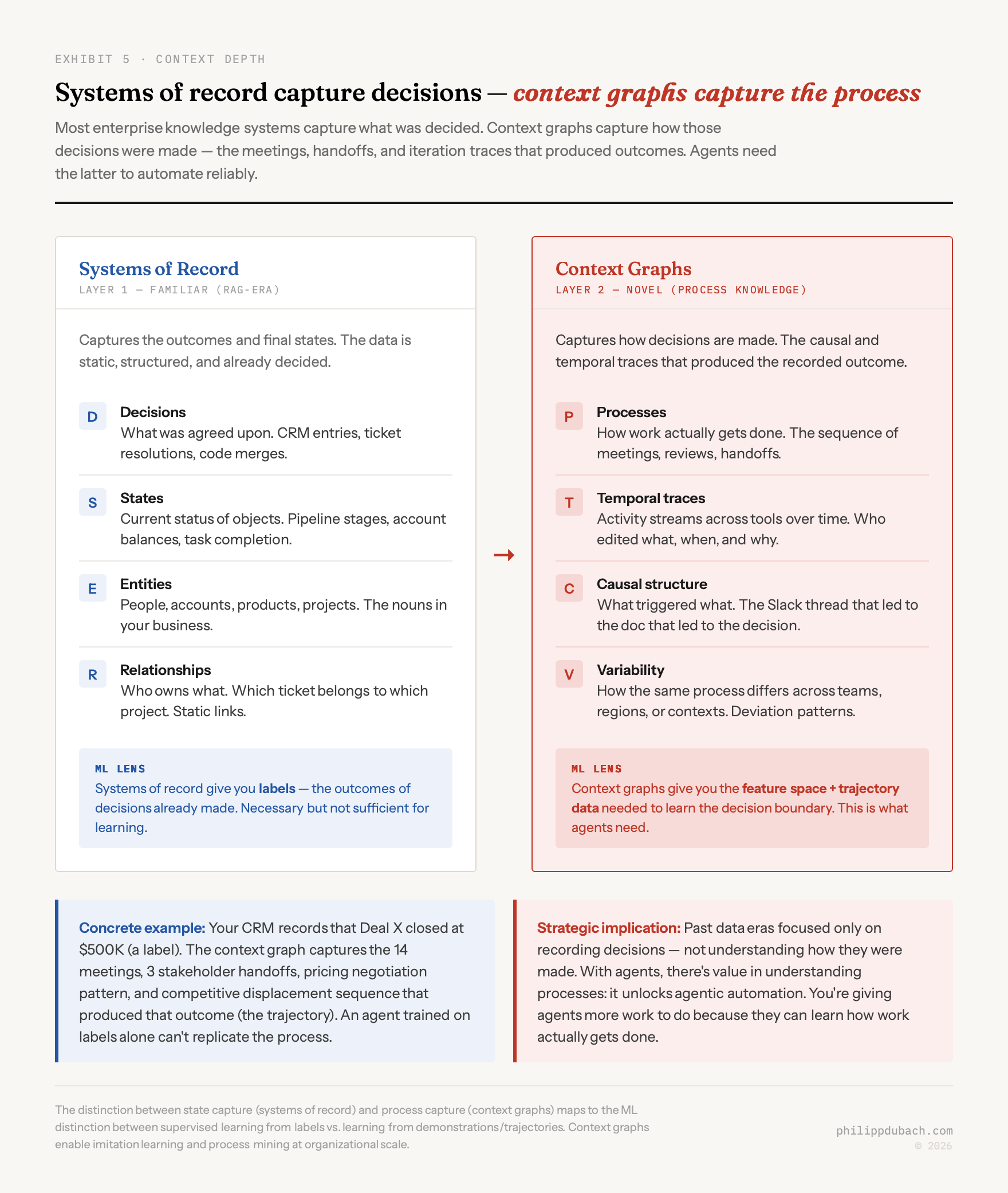

Most enterprise AI efforts operate at what I’d call Layer 1 context: connecting data sources, indexing content, enforcing permissions, retrieving relevant documents. This is the RAG-era problem set: familiar, well-understood, and increasingly commoditized. Virtually every enterprise AI platform offers connectors, vector stores, and retrieval pipelines. It matters, but it’s not where defensibility lives.

Layer 2 is where the thesis gets genuinely novel: process-level understanding. Most enterprise knowledge systems capture decisions. What ends up in the CRM, the ticketing system, the ERP. But they don’t capture how those decisions were made: the meetings, Slack threads, document iterations, handoffs, and informal coordination that produced the recorded outcome.

Through a machine learning lens, the distinction is sharp: systems of record give you labels. Context graphs give you the feature space and trajectory data you’d actually need to learn the decision boundary. Consider a concrete example. Your CRM records that Deal X closed at $500K. That’s a label. The context graph captures the 14 meetings, 3 stakeholder handoffs, the pricing negotiation pattern, and the competitive displacement sequence that produced that outcome. Those are the features and the trajectory. An agent trained on labels alone can’t replicate the process that generated them.

Through a machine learning lens, the distinction is sharp: systems of record give you labels. Context graphs give you the feature space and trajectory data you’d actually need to learn the decision boundary. Consider a concrete example. Your CRM records that Deal X closed at $500K. That’s a label. The context graph captures the 14 meetings, 3 stakeholder handoffs, the pricing negotiation pattern, and the competitive displacement sequence that produced that outcome. Those are the features and the trajectory. An agent trained on labels alone can’t replicate the process that generated them.

This is why so many early enterprise AI deployments produce outputs that are technically plausible but operationally useless. The agent has access to the what but not the how. It can retrieve the right documents but can’t reconstruct the reasoning process that a human would follow. Closing that gap, building systems that capture and encode process knowledge rather than just decision records, is the highest-value problem in enterprise AI right now.

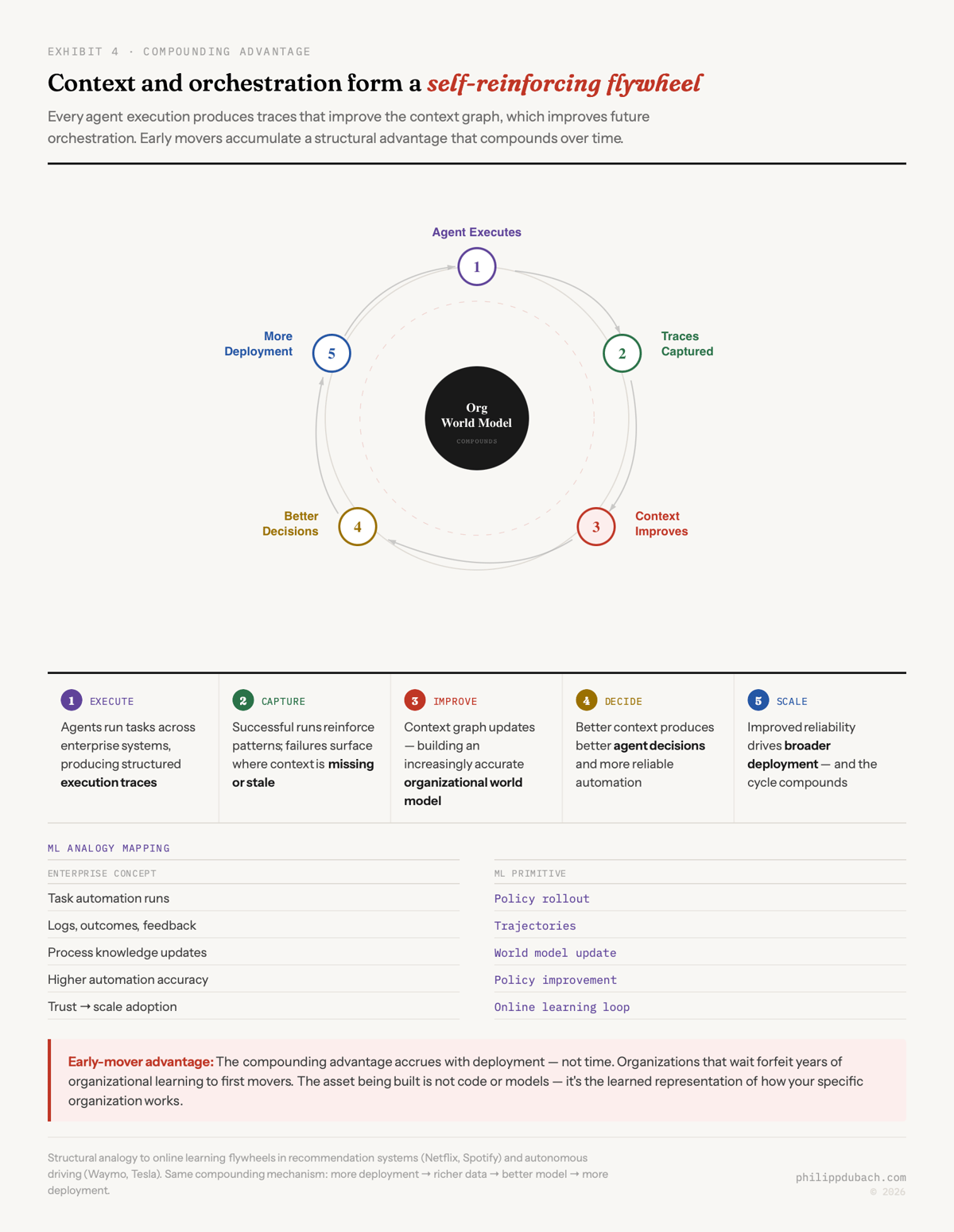

III. Context and orchestration form a compounding flywheel

There’s a reinforcement learning analogy here that I think is underappreciated. The orchestrator is the policy. The context graph is the learned world model. Agent traces are the trajectories. Every successful execution reinforces good patterns. Every failure surfaces where context is missing or stale. Over time, the system builds an increasingly accurate representation of how the organization actually operates.

And this loops back: more deployment produces richer traces, which improve the context graph, which improves agent decisions, which builds trust, which drives more deployment.

This is the same compounding mechanism that makes recommendation engines and autonomous driving systems improve with scale. Netflix gets better at recommendations because every viewing session generates training signal. Waymo gets better at driving because every mile generates edge cases. The difference here is that the asset being built isn’t a product feature. It’s an organizational world model, a learned representation of how your specific company works.

This is the same compounding mechanism that makes recommendation engines and autonomous driving systems improve with scale. Netflix gets better at recommendations because every viewing session generates training signal. Waymo gets better at driving because every mile generates edge cases. The difference here is that the asset being built isn’t a product feature. It’s an organizational world model, a learned representation of how your specific company works.

And unlike model weights, which any well-funded lab can approximate, your organization’s accumulated process knowledge is genuinely unique. No one else has your meeting patterns, your escalation sequences, your informal decision-making topology. That’s a moat.

Where this breaks, and why the agentic AI failure rate will be high

Gartner predicts 40% of enterprise applications will feature task-specific AI agents by 2026, up from less than 5% in 2025. McKinsey’s latest survey shows 23% of organizations are already scaling agentic AI, with another 39% experimenting. But Gartner also warns that over 40% of agentic AI projects will be canceled by end of 2027 due to escalating costs and unclear business value.

The gap between ambition and execution is the context problem in disguise. Without process knowledge, agents produce plausible outputs that don’t match how the organization actually works. They retrieve the right policy document but apply it without understanding the exceptions your team has developed over years. They draft the right kind of email but miss the relationship dynamics that would change the tone. The failure mode isn’t that the model is bad. It’s that the context is shallow.

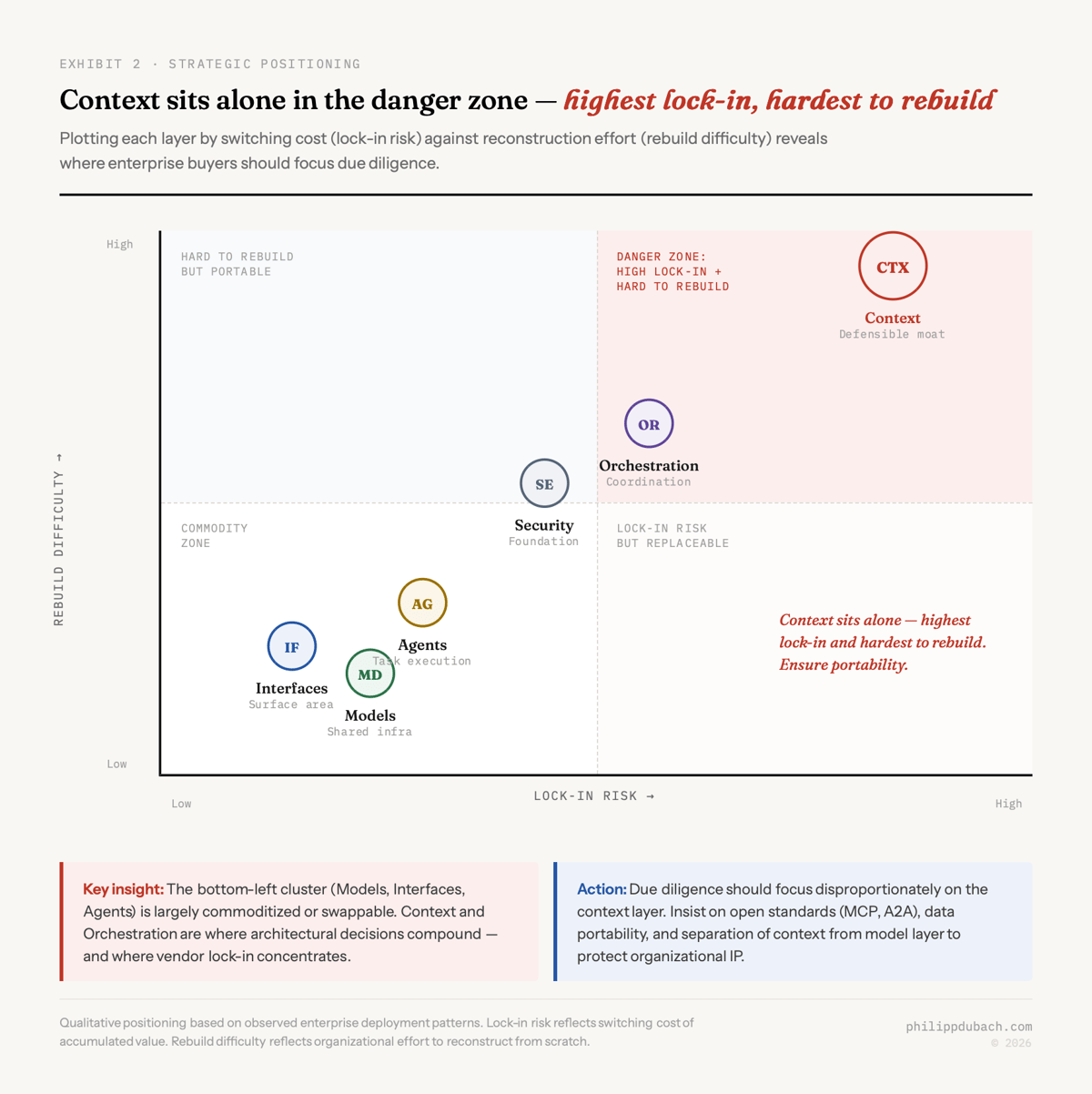

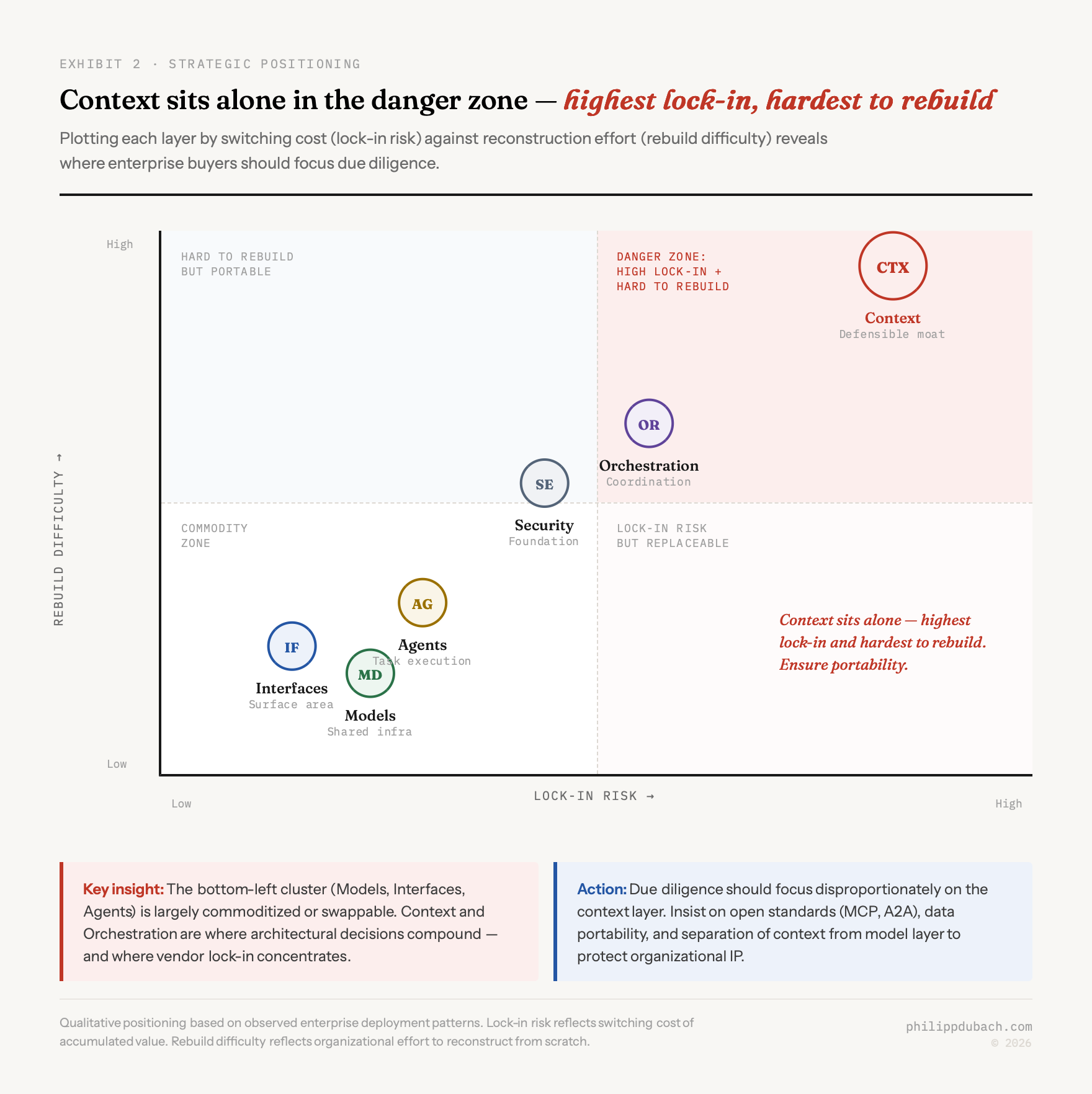

This chart tells the strategic story in one image. Models, interfaces, and agents cluster in the commodity zone: low lock-in, easy to replace. Context sits alone in the danger zone: highest lock-in risk and hardest to rebuild. That’s exactly where your due diligence should concentrate.

This chart tells the strategic story in one image. Models, interfaces, and agents cluster in the commodity zone: low lock-in, easy to replace. Context sits alone in the danger zone: highest lock-in risk and hardest to rebuild. That’s exactly where your due diligence should concentrate.

What to actually do about your agentic AI architecture

Don’t go monolithic. Each layer evolves at a different rate. Models improve quarterly, context infrastructure evolves over months, security requirements shift with regulation. Coupling them into one vendor’s all-in-one platform forces you to upgrade at the speed of the slowest-moving layer. You inherit their architectural bets, their integration timeline, their roadmap priorities. The history of enterprise software is littered with platforms that tried to own every layer and ended up mediocre at all of them.

Insist on interoperability. MCP, A2A, open connectors. If your vendor doesn’t support open standards, you’re absorbing limitations you can’t see yet. The pace of AI innovation is faster than any prior technology cycle, and you need the ability to swap in new capabilities the moment they appear without rebuilding your stack. The organizations that locked into single-vendor cloud stacks in 2015 spent years migrating out. Don’t repeat that mistake at the agent layer.

Treat context as portable IP. Your organizational world model (process knowledge, interaction history, learned workflow patterns) is the hardest-to-rebuild and most valuable asset in the stack. Ensure it is not locked to any single vendor or model provider. The right architecture separates accumulated context from the model layer so you retain your organizational IP regardless of which models or platforms you use tomorrow.

Start the flywheel early. The compounding advantage in context accrues with deployment, not with time spent evaluating. Every agent execution generates organizational learning. Companies that wait to “see how it plays out” forfeit years of compounding to first movers. This isn’t speculative. It’s the same math that governs every data flywheel business. The question isn’t whether to start. It’s whether you can afford the cost of starting late.

The stack will stratify. Specialists will outperform monoliths. Models will converge toward shared infrastructure. The defensible asset in enterprise AI is not the model. It’s the organizational world model. The organizations that start building it now, maintaining it carefully, and keeping it portable will compound their lead in the agent era. Everyone else will be buying commodity inference and wondering why their agents don’t work.