The pitch used to be simple: accept illiquidity, get rewarded. Lock up your capital for seven years, tolerate capital calls and J-curves, and in exchange you’d earn returns that public markets couldn’t touch. It was the defining bargain of institutional investing for two decades.

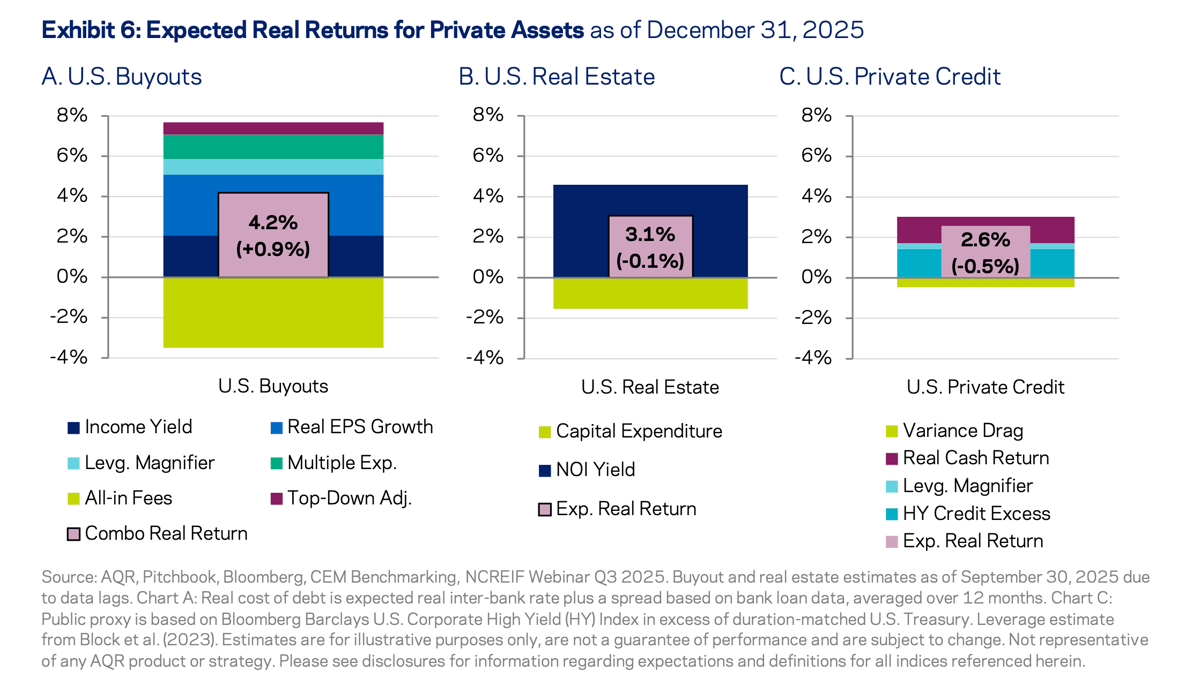

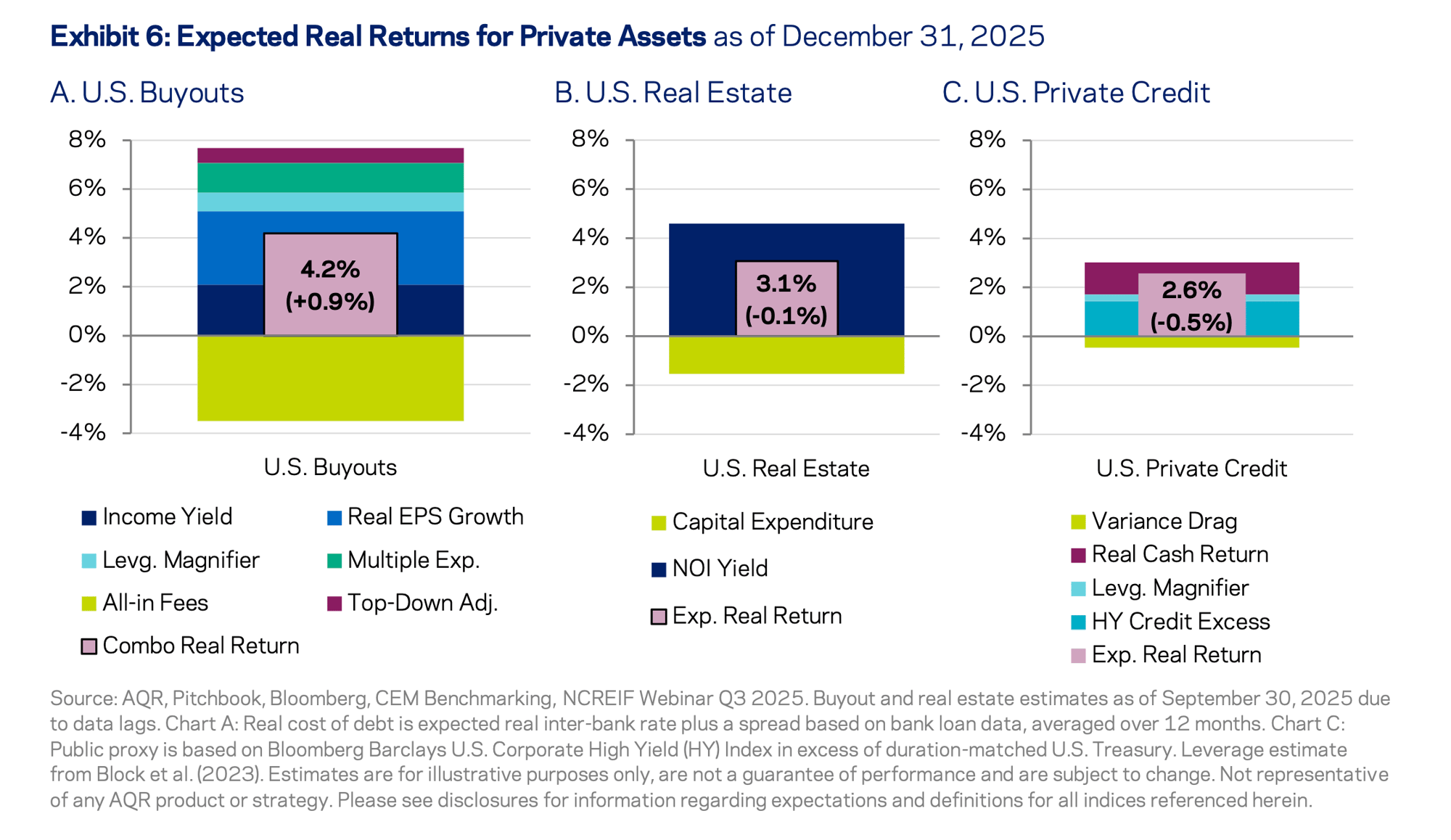

AQR’s latest capital market assumptions make for uncomfortable reading if you’re an allocator to private markets. Their expected real return for U.S. buyouts over the next 5-10 years is 4.2%. For U.S. large cap public equities, it’s 3.9%. That’s a 30 basis point premium for accepting years of lockup, unpredictable capital calls, limited transparency, and the very real risk of picking the wrong manager.

Private credit looks even worse. Expected returns dropped 0.5 percentage points year over year as spreads narrowed and base rates came down. The asset class that was supposed to be the sensible alternative to stretched equity valuations now offers less compensation than it did twelve months ago.

Private credit looks even worse. Expected returns dropped 0.5 percentage points year over year as spreads narrowed and base rates came down. The asset class that was supposed to be the sensible alternative to stretched equity valuations now offers less compensation than it did twelve months ago.

This isn’t a temporary dislocation. It’s the logical endpoint of too much capital chasing the same opportunities. When every pension fund, endowment, and sovereign wealth fund decides they need 20-30% allocation to alternatives, the returns that made alternatives attractive get arbitraged away. The money didn’t find alpha. It became beta (with a lockup).

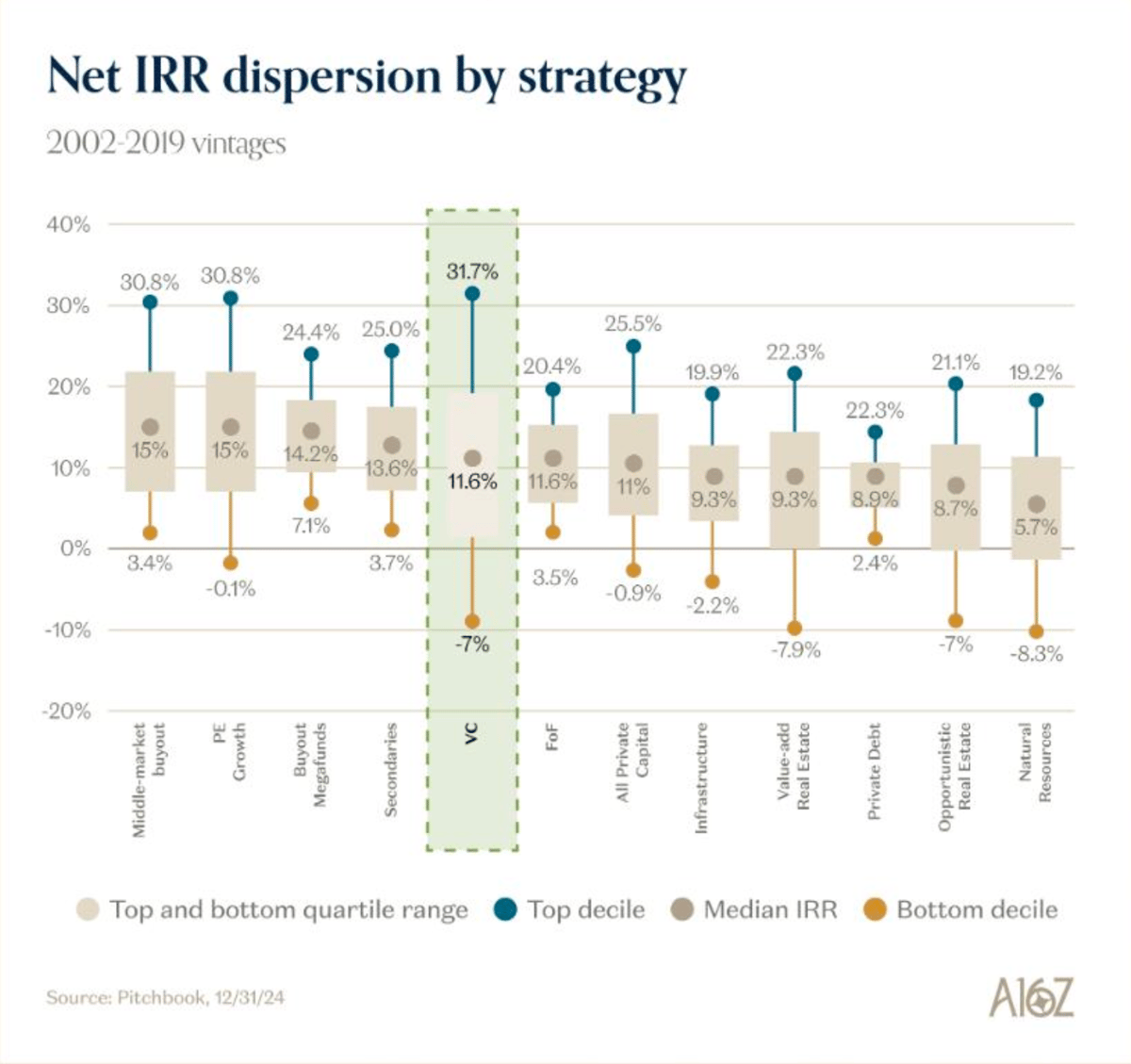

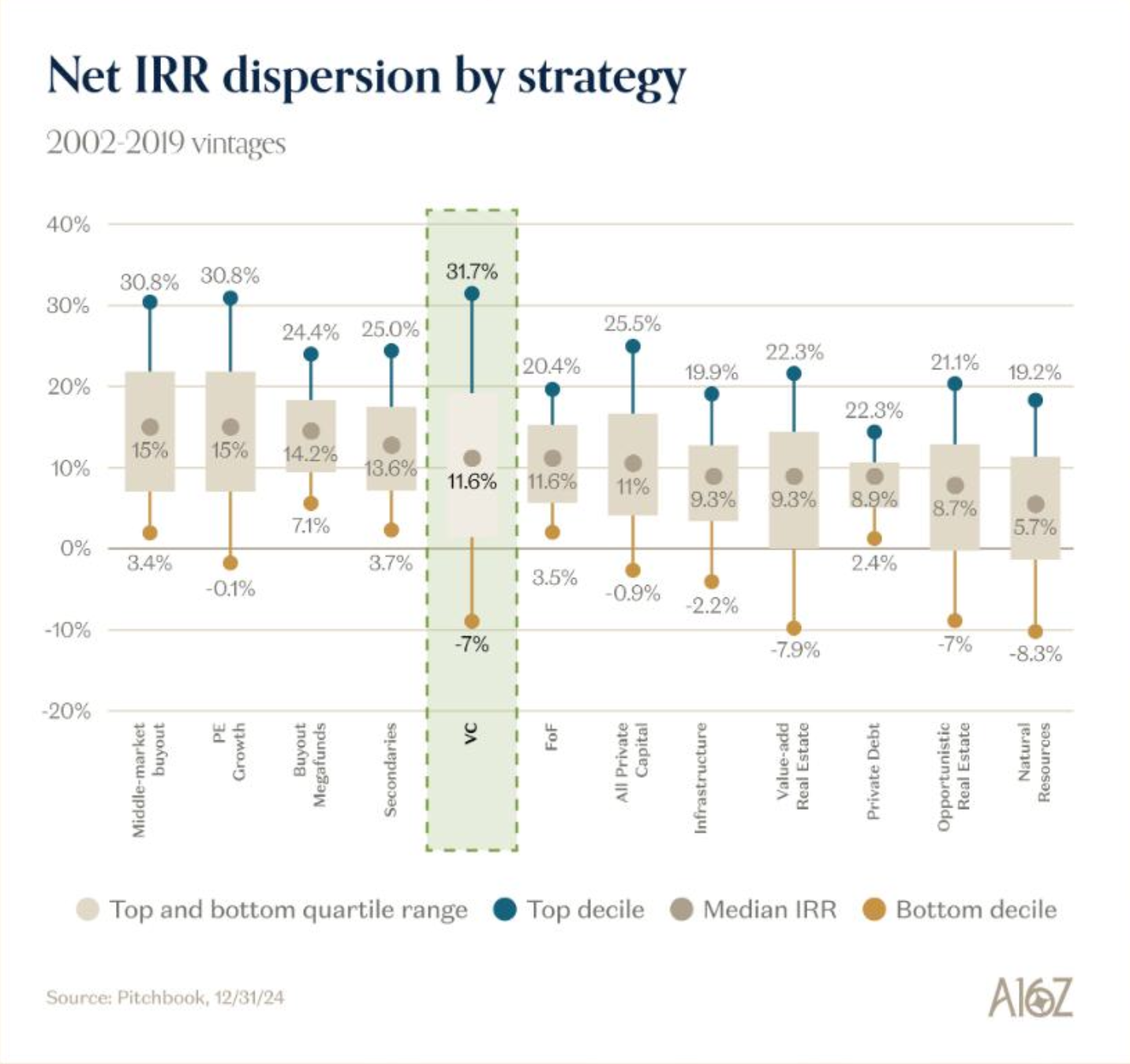

I read more reports and the a16z State of the Markets 2026 isn’t less interesting. The dispersion numbers tell an interesting story. In venture capital, top decile managers generate 31.7% IRR while bottom decile managers return negative 7%. The spread between winners and losers is enormous. But that spread is precisely why average returns have compressed. Access to top-tier funds has always been limited, and everyone else is fighting over what’s left.

AQR’s framework suggests something that few allocators want to hear: the illiquidity premium might be negative for most investors. If you’re not in the top quartile of manager selection, you’re accepting lockup risk for returns you could approximate in public markets with better liquidity and lower fees.

AQR’s framework suggests something that few allocators want to hear: the illiquidity premium might be negative for most investors. If you’re not in the top quartile of manager selection, you’re accepting lockup risk for returns you could approximate in public markets with better liquidity and lower fees.

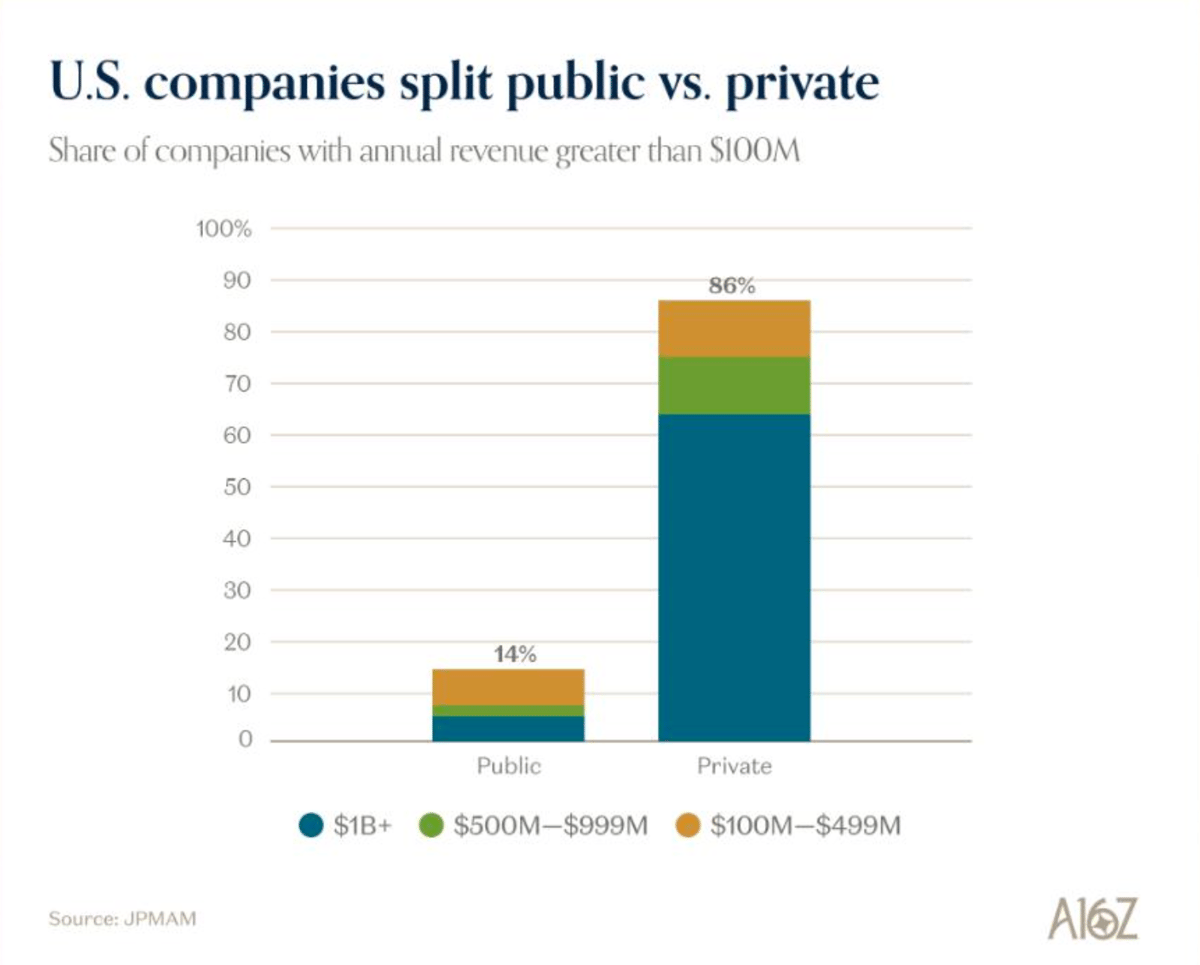

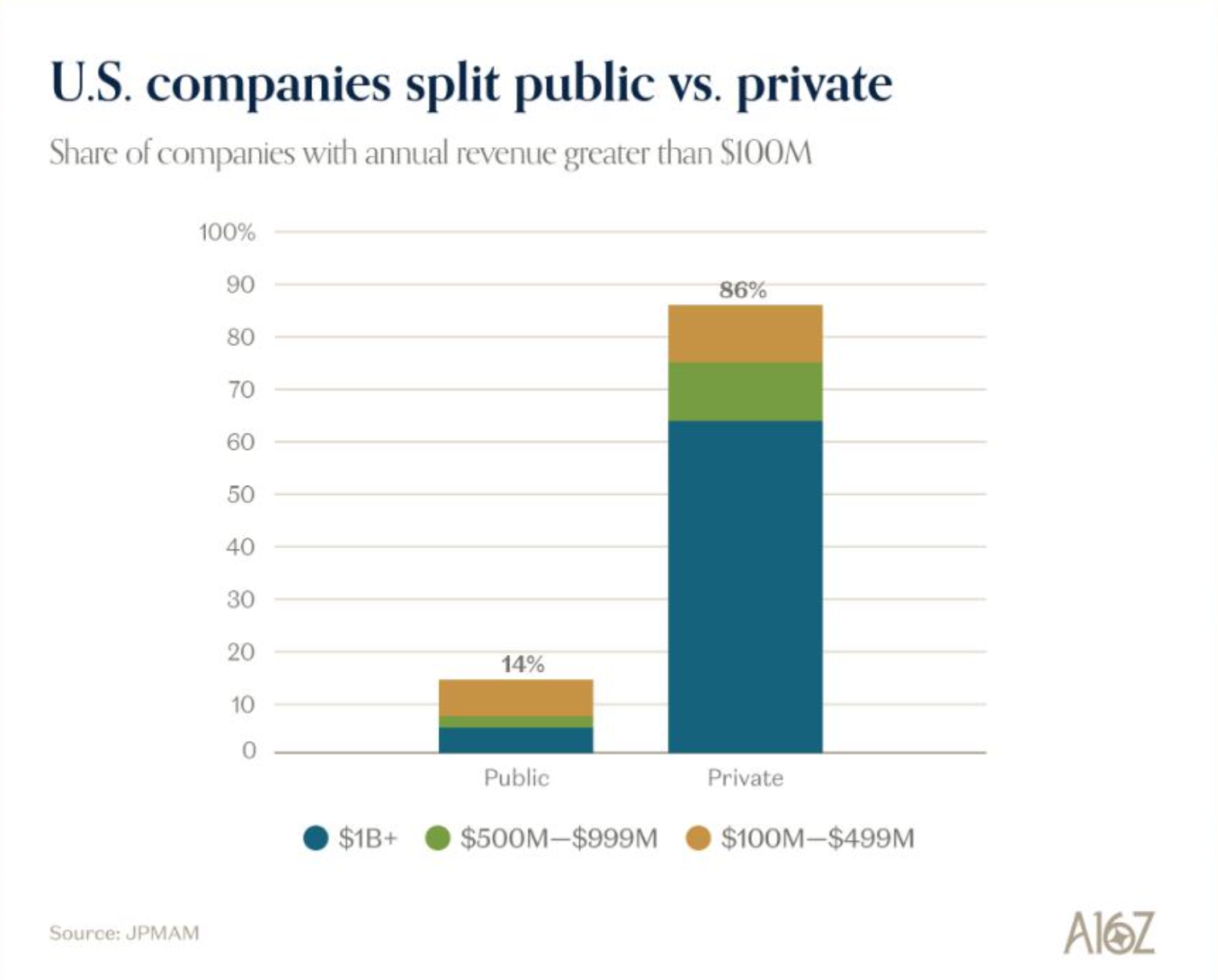

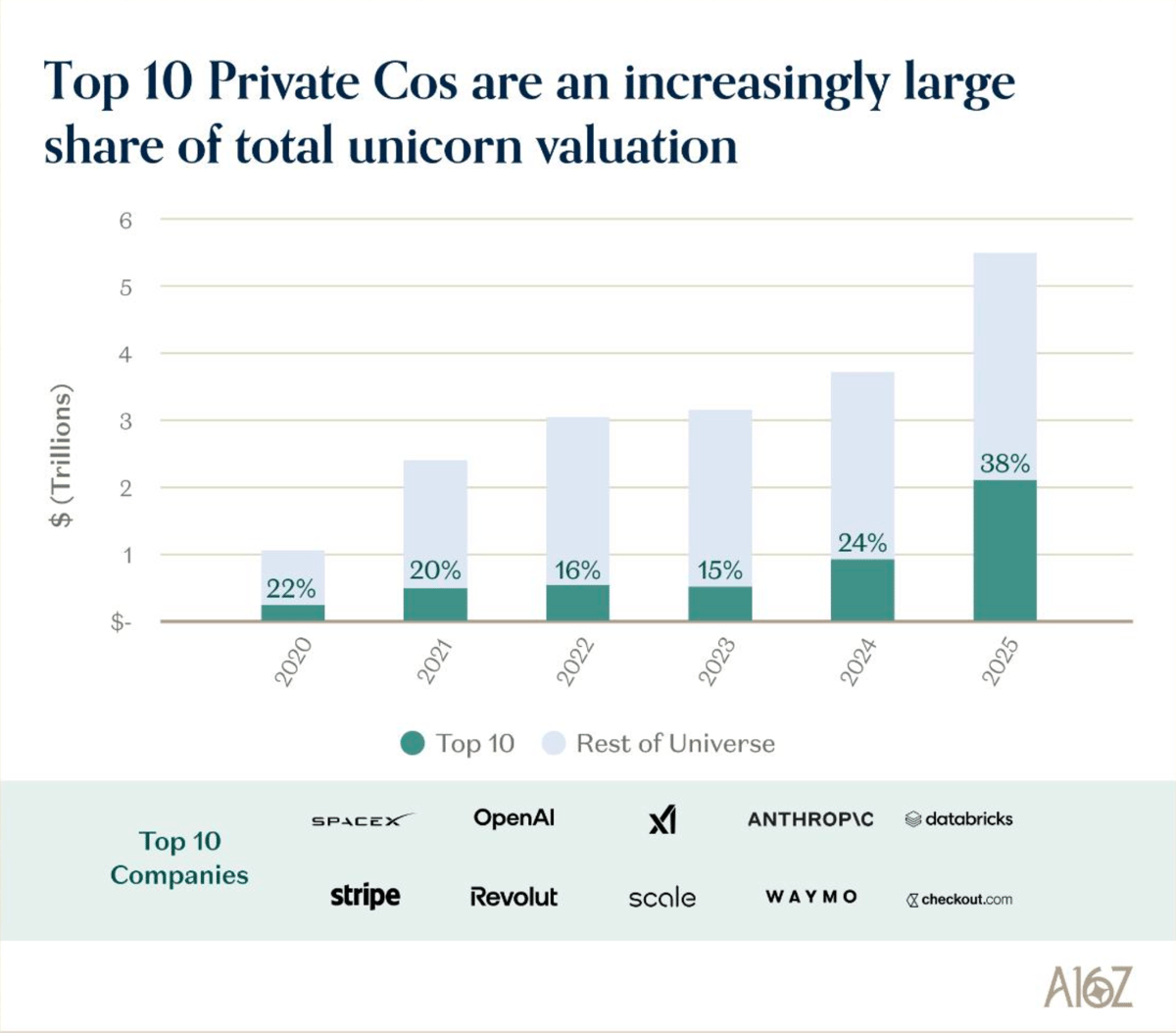

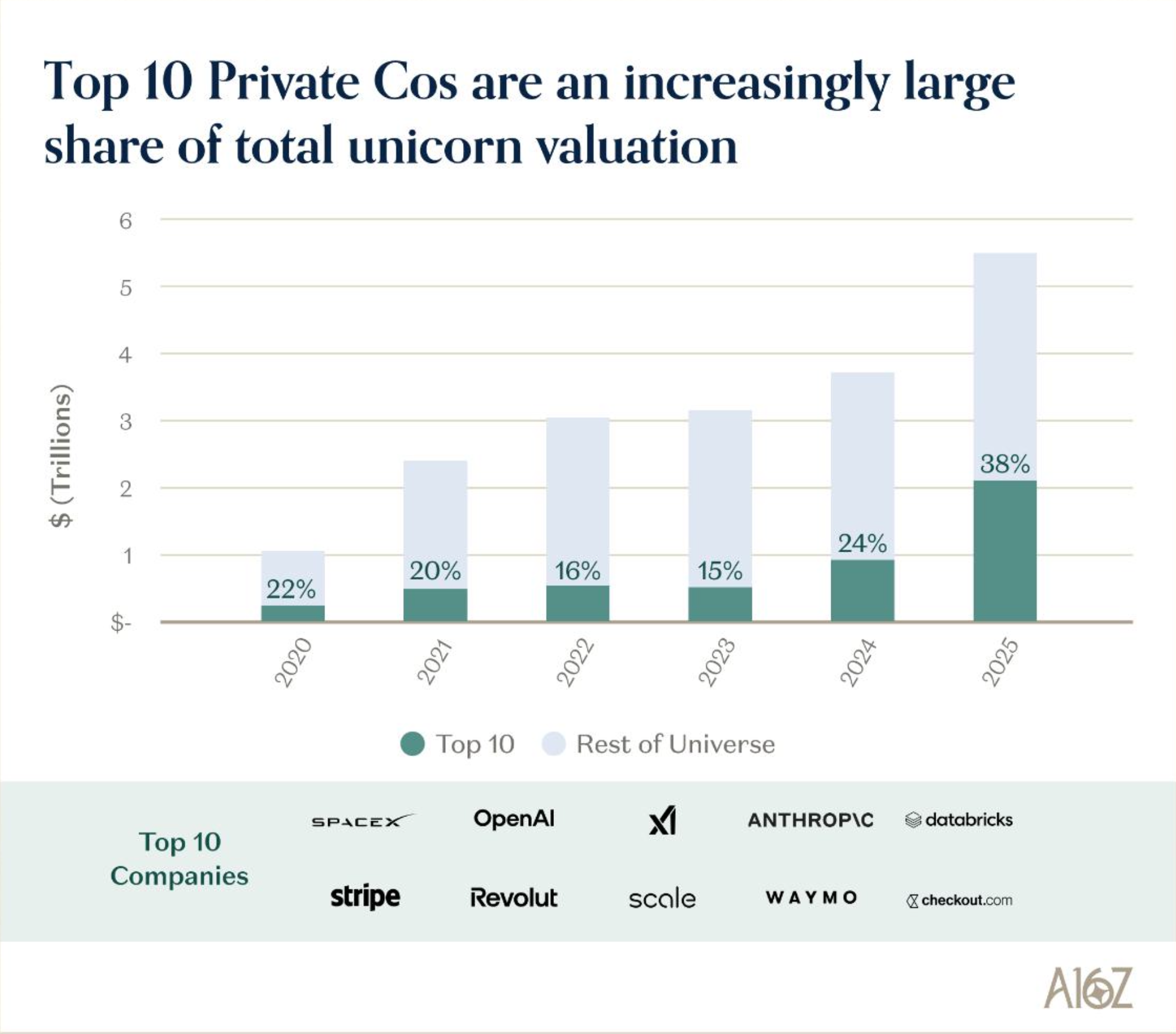

The counterargument, and it’s a reasonable one, is that private markets offer exposure to companies you simply can’t access in public markets anymore. This part is true. 87% of U.S. companies with more than $100 million in revenue are now private. The top 10 private companies represent 38% of total unicorn valuation, and that share has nearly doubled since 2020. SpaceX, OpenAI, Anthropic, Databricks, Stripe: these are category-defining businesses, and they’re not on any exchange.

But access isn’t the same as returns. You can have exposure to the most exciting companies in the world and still underperform a boring index fund if you pay too much or pick the wrong vintage. The S&P 500 minimum market cap eligibility has tripled since 2019 to $22.7 billion. Companies are staying private longer, which means more value creation happens before public investors get a chance. It also means private investors are paying up for that privilege.

But access isn’t the same as returns. You can have exposure to the most exciting companies in the world and still underperform a boring index fund if you pay too much or pick the wrong vintage. The S&P 500 minimum market cap eligibility has tripled since 2019 to $22.7 billion. Companies are staying private longer, which means more value creation happens before public investors get a chance. It also means private investors are paying up for that privilege.

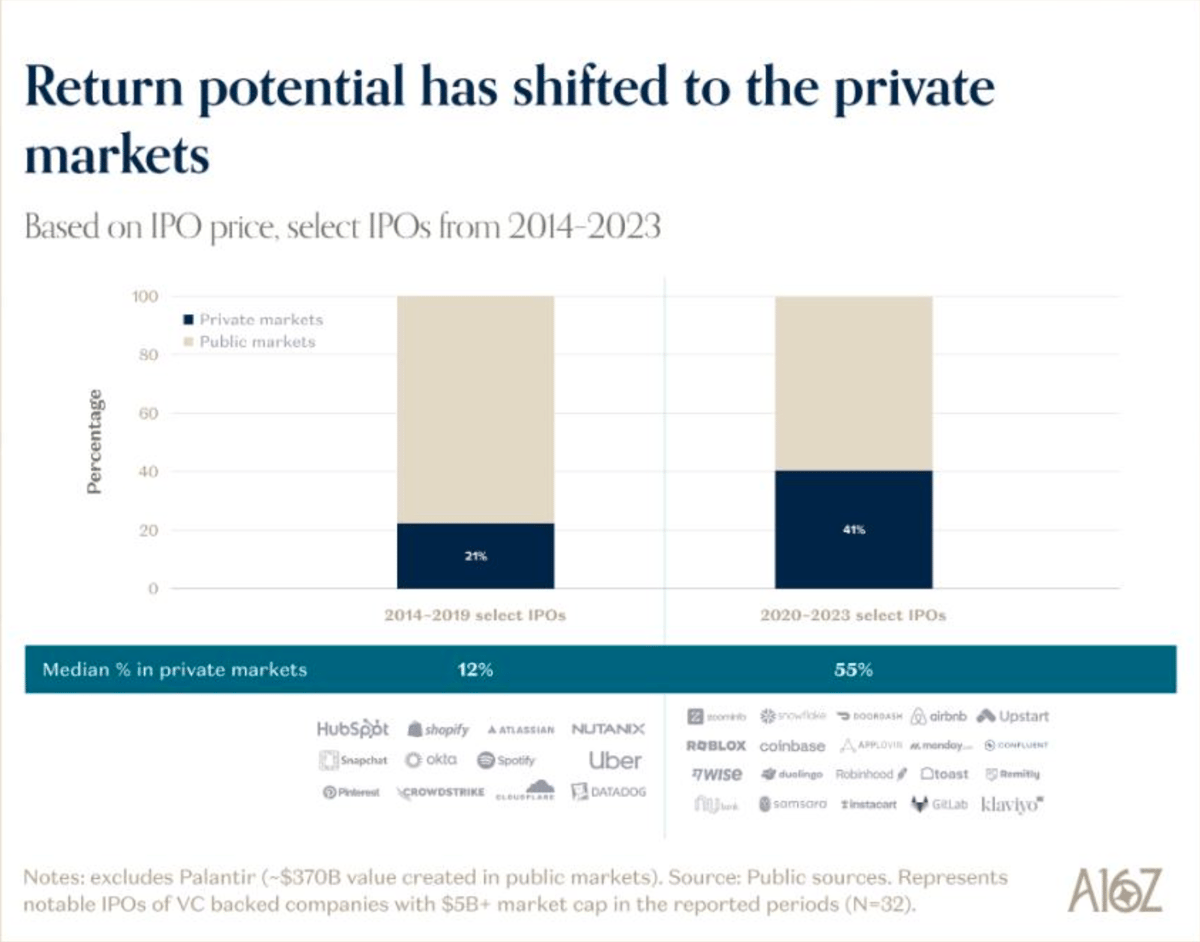

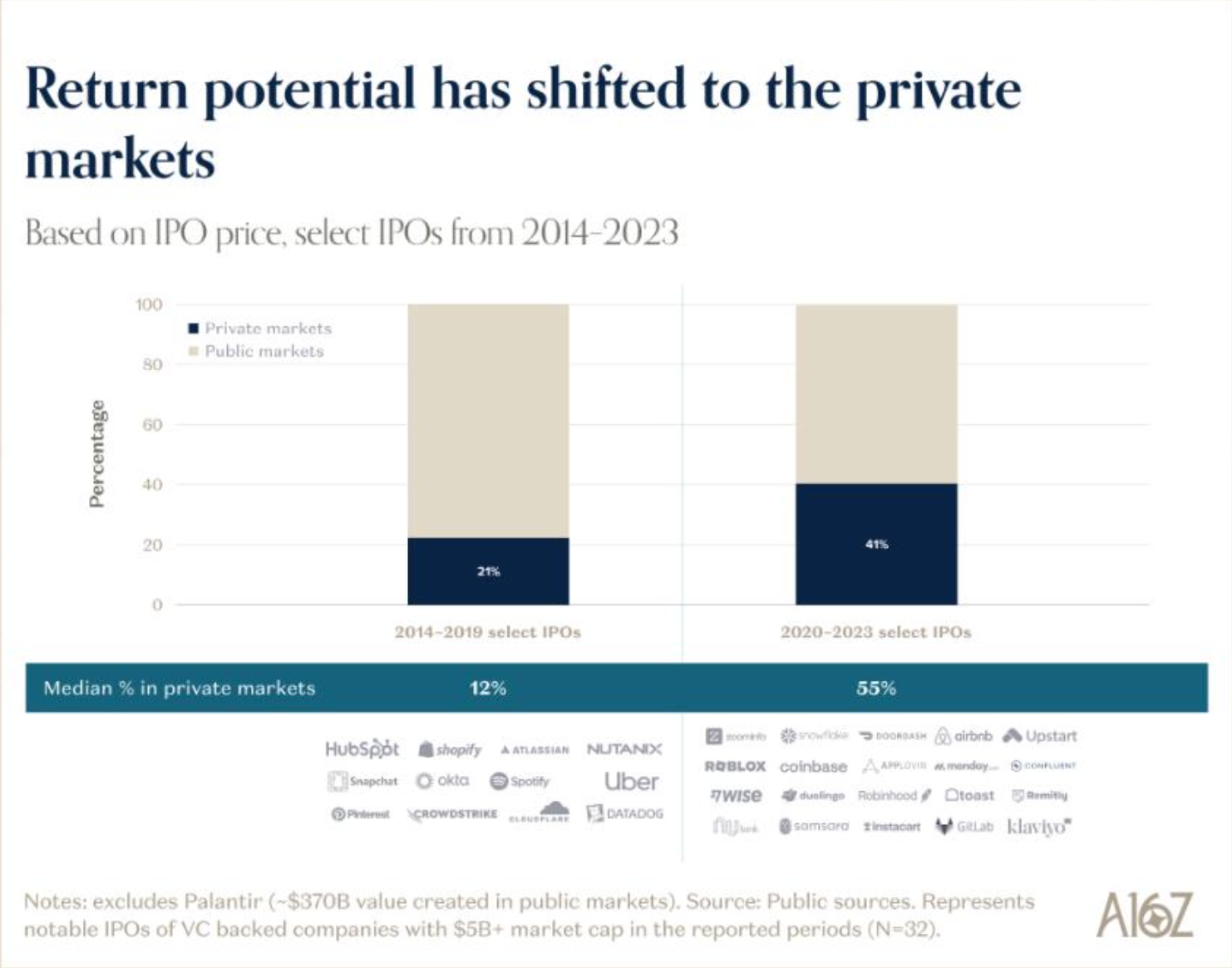

Value creation has moved earlier in the company lifecycle. For IPOs between 2014-2019, only 12% of median value was created in private markets. For 2020-2023 IPOs, that number jumped to 55%. If you want to capture returns from the next generation of important companies, you probably need private market exposure.

The question really is what you’re paying for it.At 4.2% expected returns versus 3.9% for public equities, you’re paying in liquidity and flexibility for almost nothing in expected return. The premium that justified the allocation model has been competed away. If you’re in the top 5% of venture funds earning 60%+ IRR, none of this applies. For everyone else, the world has moved on.

The question really is what you’re paying for it.At 4.2% expected returns versus 3.9% for public equities, you’re paying in liquidity and flexibility for almost nothing in expected return. The premium that justified the allocation model has been competed away. If you’re in the top 5% of venture funds earning 60%+ IRR, none of this applies. For everyone else, the world has moved on.