Something strange is happening in the food industry. New US dietary guidelines call for more protein and less sugar. Greggs, the UK bakery chain, just warned of “flatlining profits” in the food-to-go market. Food companies are racing to overhaul their brands, ditching artificial dyes and packing protein into products. Earnings calls across the sector blame “inflation” and “subdued consumer confidence.” Nobody mentions the elephant in the room: GLP-1 medications.

New research from Cornell finally puts numbers to what the food industry doesn’t want to discuss. Using transaction data from 150,000 households linked to survey responses on medication adoption, Sylvia Hristakeva, Jūra Liaukonytė, and Leo Feler tracked exactly how Ozempic and Wegovy users change their spending. The results deserve attention from anyone holding food stocks.

The headline: households with a GLP-1 user cut grocery spending by 5.3% within six months. For high-income households, that figure jumps to 8.2%. Fast food takes an even harder hit, with spending at limited-service restaurants falling 8.0%. These aren’t people switching brands or trading down. They’re simply eating less.

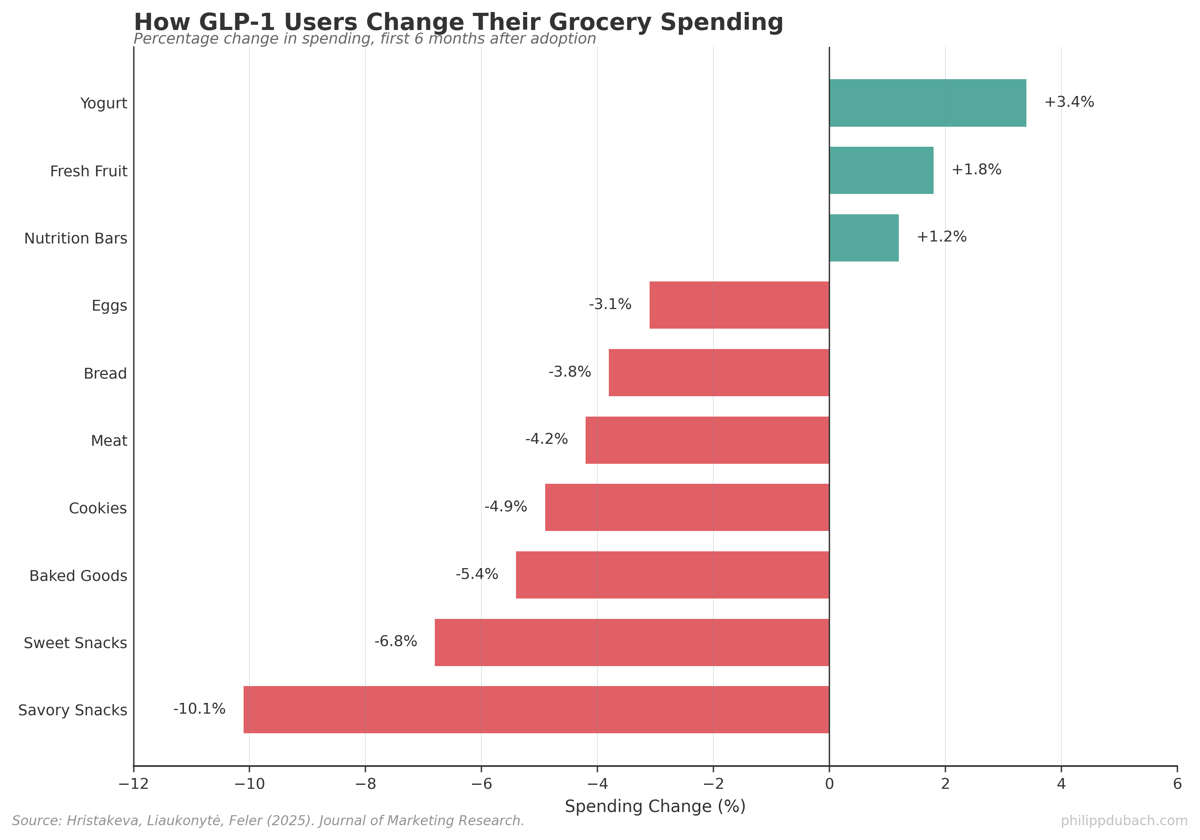

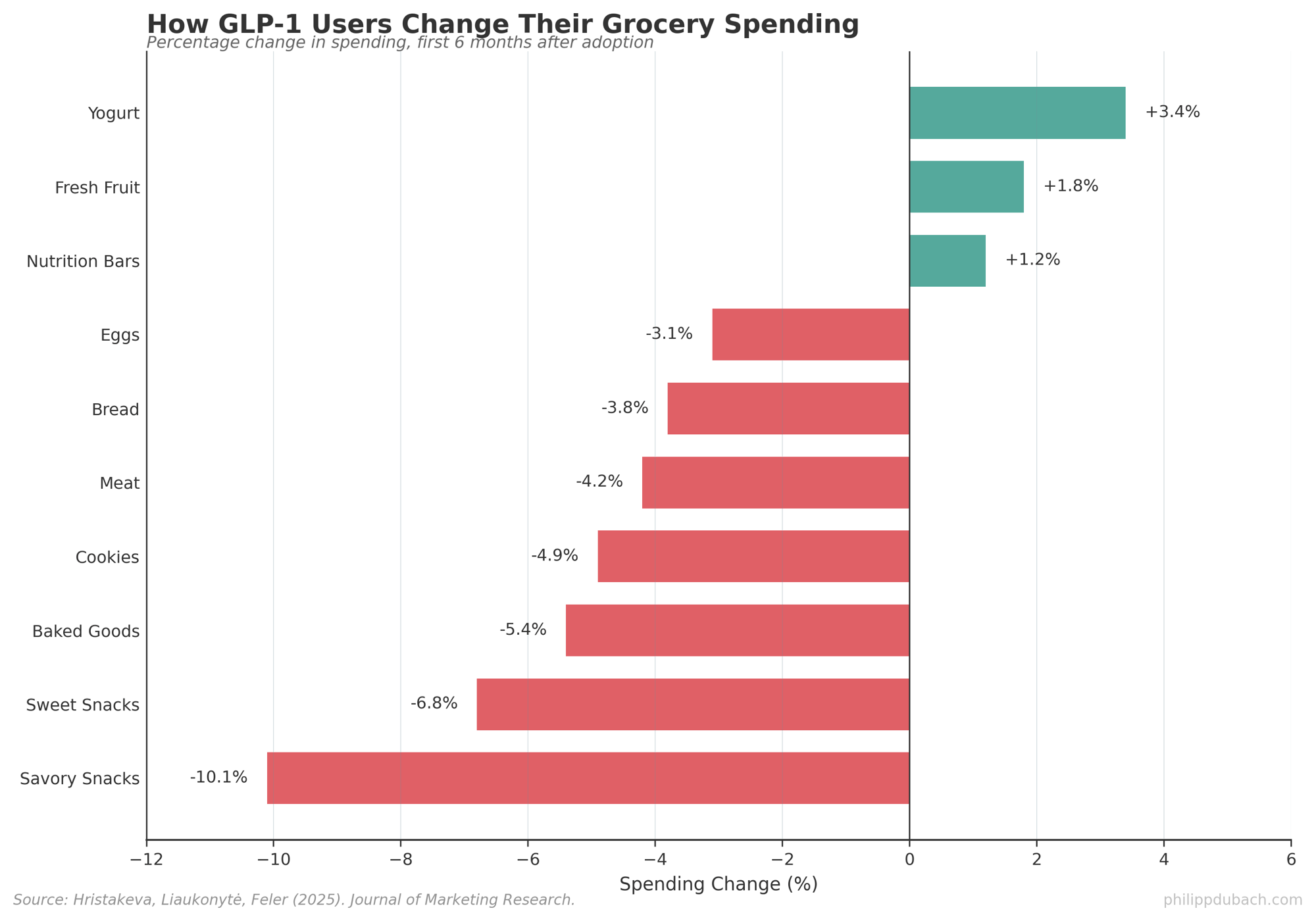

The category-level data tells the real story. Savory snacks see the largest decline at 10.1%. Sweets, baked goods, cookies, all down. Even staples like meat, eggs, and bread decline. In the entire grocery basket, only one category shows a statistically significant increase: yogurt. Fresh fruit and nutrition bars trend up slightly, but yogurt is the lone winner with statistical confidence.

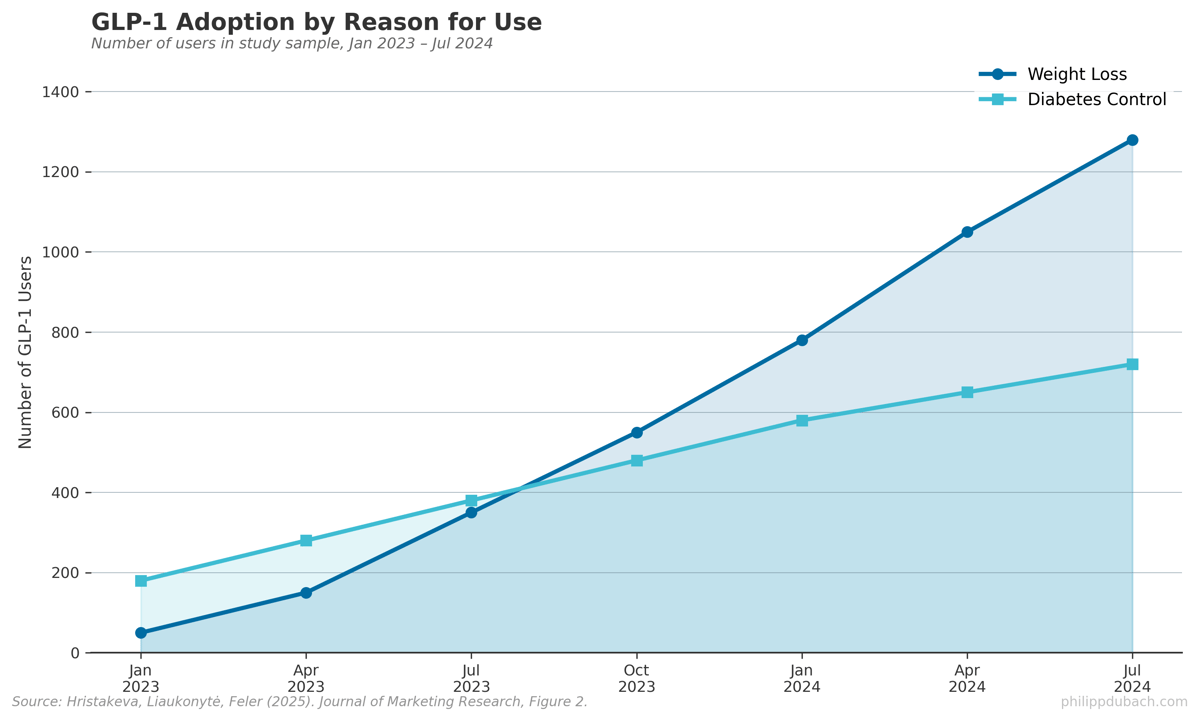

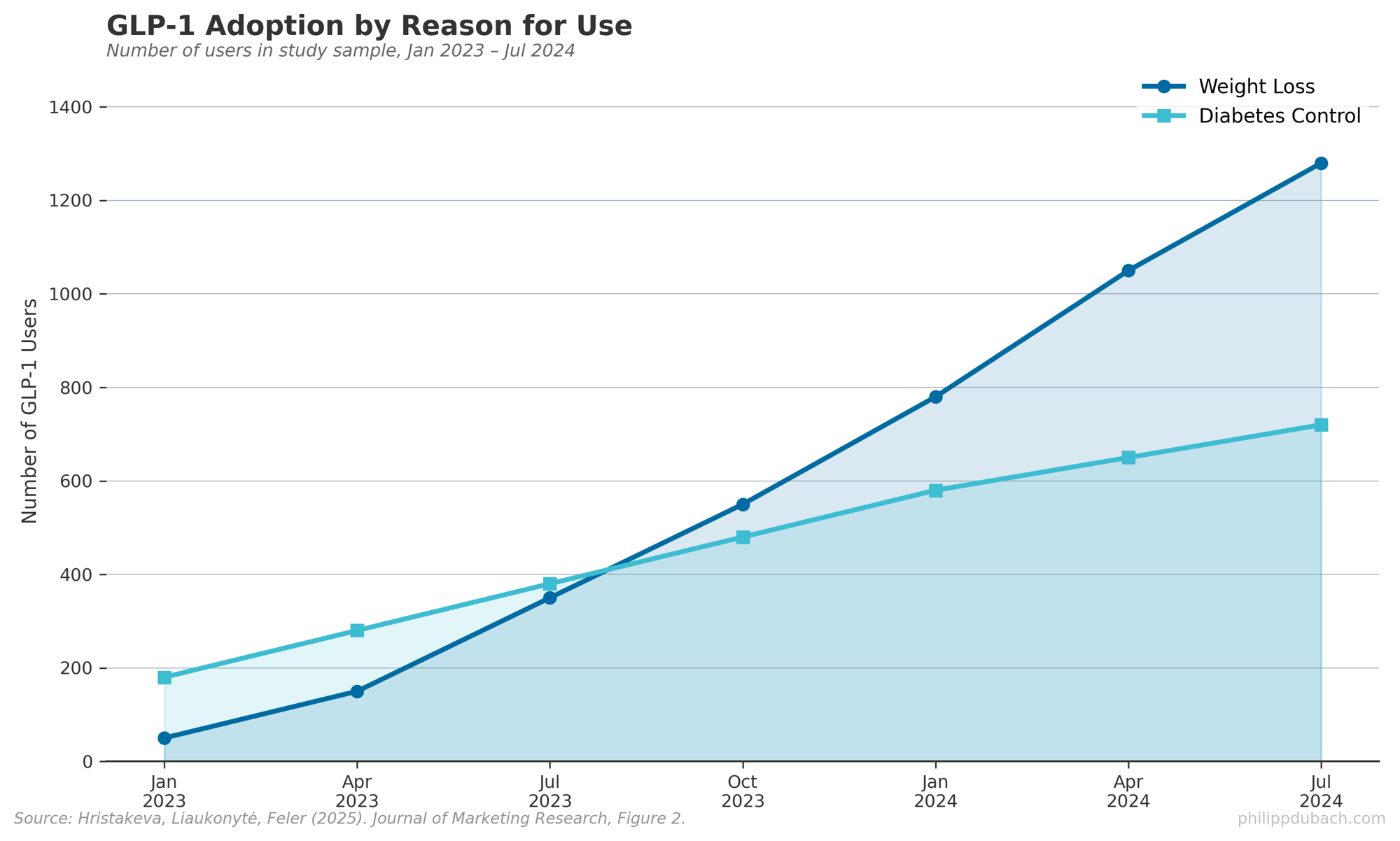

As of July 2024, 16.3% of U.S. households have at least one GLP-1 user. The adoption curve is steepening. Nearly half of adopters report taking the medication specifically for weight loss rather than diabetes management. These weight-loss users tend to be younger, higher income, and more willing to pay out of pocket. They’re also the most profitable customers for fast food chains, the ones who don’t flinch at price increases.

As of July 2024, 16.3% of U.S. households have at least one GLP-1 user. The adoption curve is steepening. Nearly half of adopters report taking the medication specifically for weight loss rather than diabetes management. These weight-loss users tend to be younger, higher income, and more willing to pay out of pocket. They’re also the most profitable customers for fast food chains, the ones who don’t flinch at price increases.

This creates what the researchers call a “double whammy” for the food industry. Companies are losing their highest-margin customers to a biological shift in appetite while being left with a more price-sensitive demographic that actually does respond to inflation. When McDonald’s CEO Chris Kempczinski talks about losing lower-income customers to home cooking, he’s describing the wrong problem.

The research also suggests why food executives might be keeping quiet. About 34% of GLP-1 users discontinue within the sample period. When they stop, their spending doesn’t just return to baseline. It becomes less healthy. Candy and chocolate purchases rise 11.4% above pre-adoption levels after stopping the medication.

The research also suggests why food executives might be keeping quiet. About 34% of GLP-1 users discontinue within the sample period. When they stop, their spending doesn’t just return to baseline. It becomes less healthy. Candy and chocolate purchases rise 11.4% above pre-adoption levels after stopping the medication.

If you’re running a snack company, the math might look survivable: lose customers to Ozempic for a year, then welcome them back once they quit. The drugs suppress appetite biologically; they don’t teach new habits. When the biology reverts, so does the behavior.

Scott Galloway has called the food industry an “obesity index” and predicted a “tsunami of shareholder destruction.” The Cornell data suggests he’s directionally right but possibly too aggressive on timing. The industry has a built-in buffer: medication discontinuation. The question is whether that buffer lasts as drugs get cheaper, side effects improve, and insurance coverage expands.

The deeper issue is about the persistence of dietary change. Previous studies found that even major life events, a diabetes diagnosis, job loss, childbirth, produce only modest and short-lived changes in diet. Information campaigns and price nudges have mixed results at best. GLP-1 medications work differently because they alter the biological reward system directly. Users describe the experience as “silencing food noise,” a constant background hum of cravings that simply disappears.

But this biological dependence cuts both ways. The changes don’t stick without the drug. Stopping medication means losing both the appetite suppression and whatever habits might have formed during treatment. The Cornell team notes that “GLP-1s could complement existing nutritional interventions” but cautions that “their broader public health relevance ultimately depends on sustained adherence.”

For investors, the practical question is positioning. Companies selling hyperpalatable, calorie-dense products face structural headwinds. Companies selling protein-rich, nutrient-dense foods in smaller portions have tailwinds. The data shows users shifting toward yogurt, fresh fruit, and nutrition bars. Package sizes may need to shrink. Marketing strategies may need to pivot from “craveable” to “satisfying.”

The next few quarters of earnings calls will be interesting. At some point, an analyst will ask the GLP-1 question directly. The honest answer from management would be: we don’t know the full impact yet, but 16% of households having a user, 8% declines in fast food spending, and the fastest-growing prescription category in the country is not something we can ignore.