A 30-second Super Bowl ad costs $8 million. That’s $267,000 per second, roughly the median U.S. home price for every tick of the clock. Super Bowl LX drew 124.9 million average viewers with a peak of 137.8 million, the highest peak audience in American television history. The NFL accounted for 84 of the top 100 most-watched U.S. telecasts in 2025. The Oscars, by comparison, managed 19.7 million.

Ro (that’s the name of the direct-to-patient telehealth company) CEO Zachariah Reitano, writing from direct experience as a 2026 Super Bowl advertiser, published a detailed cost breakdown based on his own spending and interviews with 10+ brands. The picture that emerges is considerably more expensive than the headline number. Production runs $1–4 million for studio, crew, and post-production before any famous face enters the frame. Celebrity endorsement talent adds $1–5 million, with the current A-list sweet spot at $3–5 million according to WME agent Tim Curtis. Then comes the companion buy: for every 30-second slot, advertisers are generally required to commit to spending an equivalent amount on other programs broadcast by the same network. For NBC’s 2026 Super Bowl, that meant additional inventory across the Winter Olympics and NBA All-Star Game, adding another $7–10 million to the tab.

Total committed spend: $16–23 million for a single 30-second spot. CFO.com’s Jason Hershman brackets the full range at $15–50 million depending on ambition.

For companies already spending nine figures annually on marketing, the framing of a Super Bowl ad as a “portfolio bet with capped downside” applies to virtually any marketing investment at that scale. It’s whether that $10 million generates more value here than in the other places you’ve been spending $10 million. The observation is reductive but directionally useful: the special-ness of the Super Bowl needs to be demonstrated in the data, not assumed from the vibes. But then on the other hand, as Matt Levin puts it, it’s comparably cheap:

One thing that the ads made me think about is how cheap Super Bowl advertising is, for an AI company. A Super Bowl spot costs something like $10 million for airtime plus another few million to produce, for a total at the high end of maybe $20 or $30 million, or roughly the cost of paying one employee for one month at a leading AI lab. Mark Zuckerberg carries around $30 million in his wallet in case he runs into an OpenAI engineer at Starbucks. The cost of creating a cutting-edge AI model — in compute and researcher pay — is astronomical in a way that makes the cost of any advertising, even Super Bowl advertising, look like nothing.

But let’s look at the data.

The CPM looks reasonable. Everything else is complicated.

At $8 million reaching roughly 125 million viewers, the Super Bowl’s effective CPM lands around $63–65 per thousand impressions. Standard primetime TV runs $20–30. Streaming TV sits at $15–35. TikTok charges $5–10. Digiday calculated that for the same $8 million media buy, an advertiser could purchase 1.6 billion TikTok impressions, 267 million Google search impressions, or a primetime network TV spot every night for four months.

But CPM comparisons are misleading here because they treat all impressions as equivalent. They aren’t. The Super Bowl is the last true monoculture event in American media, and the only advertising environment where the ads are the product. People rewatch them, rank them, discuss them at work Monday morning. The Today Show airs them as content. EDO, a TV outcomes measurement company, found that a single Super Bowl ad generates the same brand-search engagement as 1,056 primetime ads.

There is academic evidence on Super Bowl ad ROI

The most rigorous study comes from Wesley Hartmann at Stanford GSB and Daniel Klapper at Humboldt University, published in Marketing Science. Using Nielsen data across 55 media markets and six years of Super Bowls, they exploited exogenous variation in viewership (specifically, ratings spikes caused by local team participation) to estimate causal effects. Their results: Budweiser earned an extra $96 million from Super Bowl advertising, a 172% return on investment. Budweiser’s short-run sales revenue ran 15.75% higher per household than competitors in the weeks following the game.

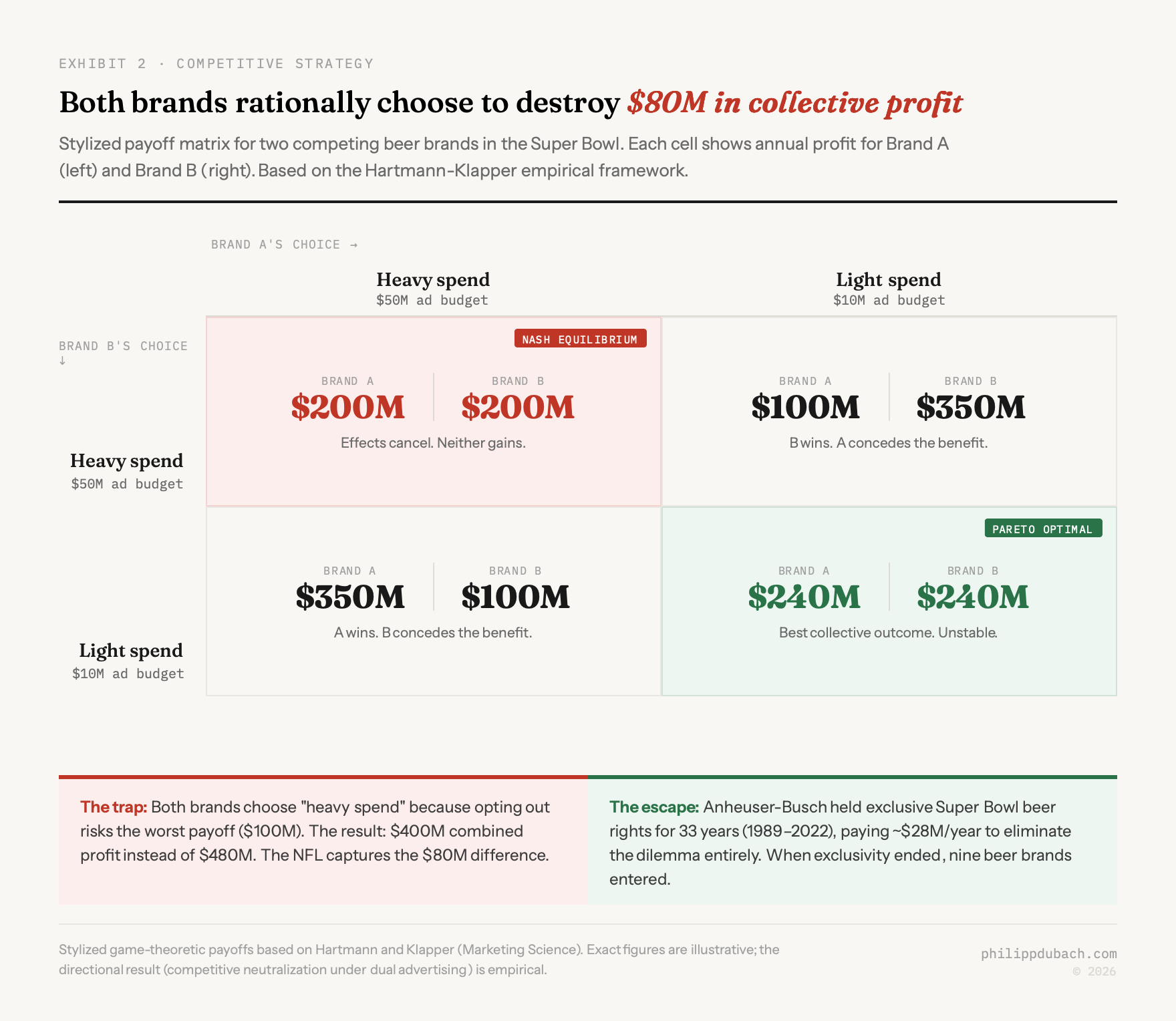

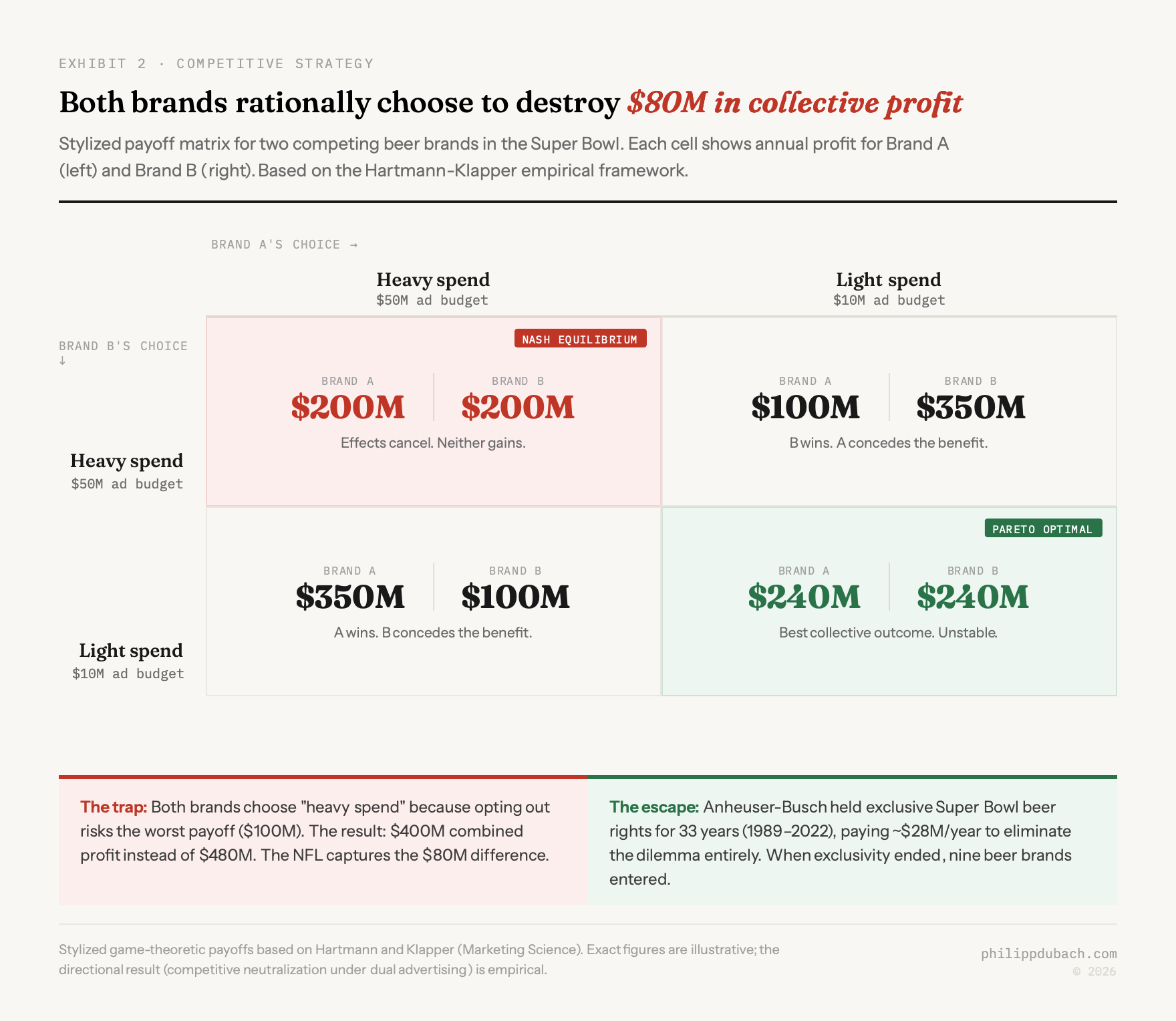

But Hartmann and Klapper’s most important finding on ad effectiveness is that when two brands in the same product category both advertise, neither gains incremental profit. The effects cancel out. Coca-Cola and Pepsi have both advertised annually in the Super Bowl for years. The researchers found no statistically significant volume increase for Coca-Cola regardless of whether it advertised, and the direction of the coefficients, if anything, suggested a negative relationship. The entire soda category’s Super Bowl spending appears to be a value-destroying exercise that neither side can unilaterally exit.

This is a textbook prisoner’s dilemma. Game theory applied to advertising predicts exactly this outcome: if Bud Light and Coors Light both spend $50 million on ads, they each profit $200 million. If both spend only $10 million, they each profit $240 million. Both rationally choose $50 million.

Anheuser-Busch understood this and paid to avoid it. The company held exclusive beer advertising rights for 33 consecutive years (1989–2022), spending $278 million over a decade partly to prevent competitive neutralization. When exclusivity ended in 2023, the Super Bowl immediately featured nine beer ads from multiple brands. Budweiser’s ROI almost certainly declined.

Stock price studies paint a muddier picture. An MDPI Sustainability study examining 272 ads from 142 firms (2010–2019) found positive cumulative abnormal returns of 2.35% over 10 days post-game. Bridgewise, covering 2021–2024, found the opposite: a portfolio of Super Bowl advertisers underperformed the S&P 500 by 9.2% after six months, with only 25% of individual advertisers outperforming. Kantar’s analysis reports an average ROI of $4.60 per dollar spent, a figure broadly consistent with their multi-year tracking. A Georgia Southern study by Eastman and Iyer found that USA Today Ad Meter likeability scores, the industry’s most-cited metric for judging Super Bowl ads, had no significant relationship with financial effectiveness.

Attribution is difficult

I always wondered how well attribution works. It seems mostly guesswork to me. The evidence suggests this is more right than wrong, though “guesswork” understates the sophistication of modern marketing attribution tools while overstating their accuracy. A 2024 Ascend2 survey found that only 29% of marketers are “extremely confident” in their attribution accuracy. More than a third of CMOs do not fully trust their own marketing data. The structural problems are formidable: privacy signal loss from GDPR, CCPA, and iOS opt-outs has degraded observable data. Cross-device fragmentation means customers touch 3–5+ devices before converting. Platform self-reporting creates systematic overcounting, with Google, Meta, and Amazon each claiming credit for the same sale.

For Super Bowl ads specifically, the attribution challenge is amplified by confounding. Brands run concurrent promotions, digital retargeting campaigns, influencer activations, and PR blitzes. Many release ads days before the game. Academic research suggests pricing relative to competition has 20–25x greater impact on sales than total advertising across all channels, which means a coincidental price change during Super Bowl week can wash out the advertising signal entirely.

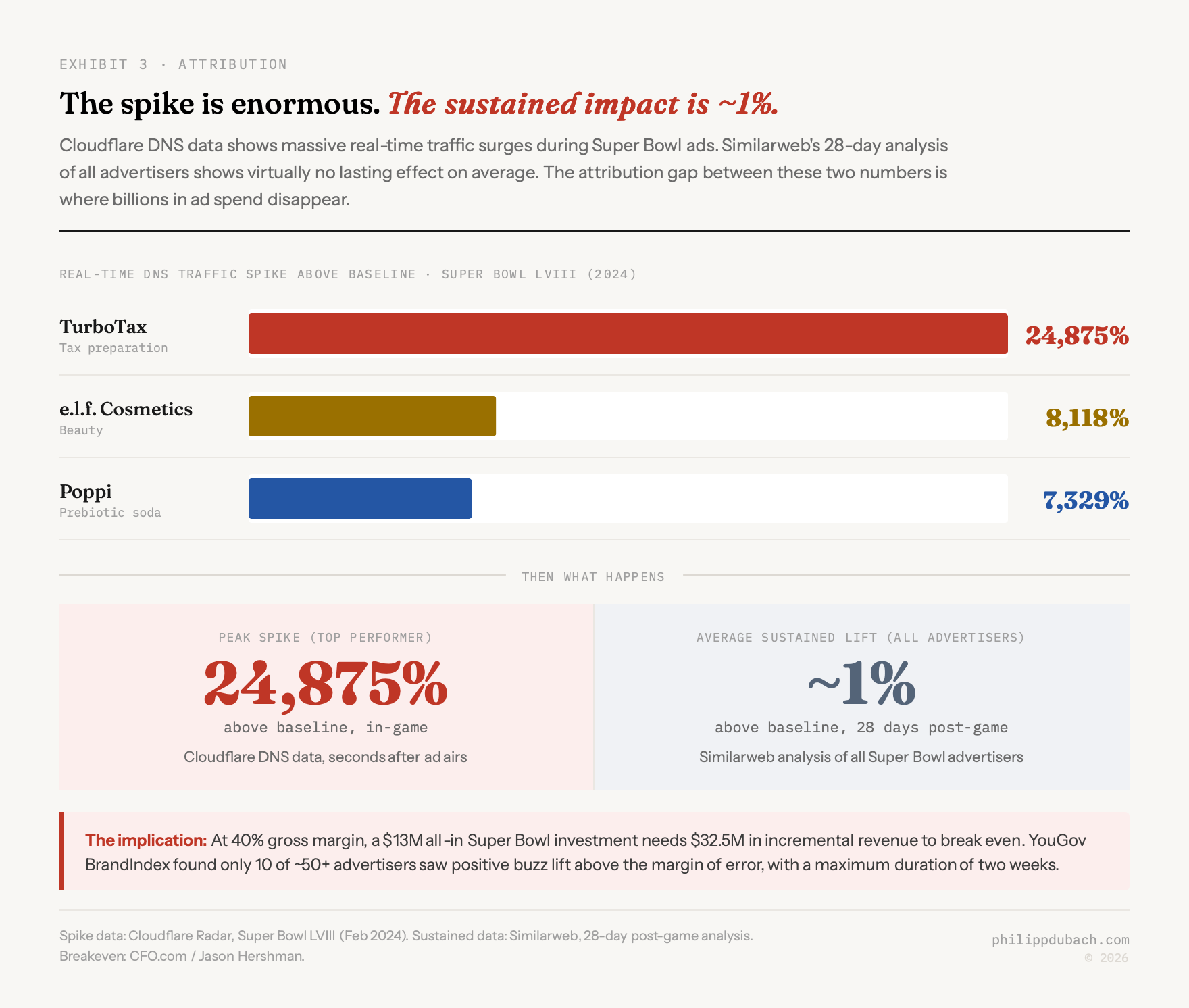

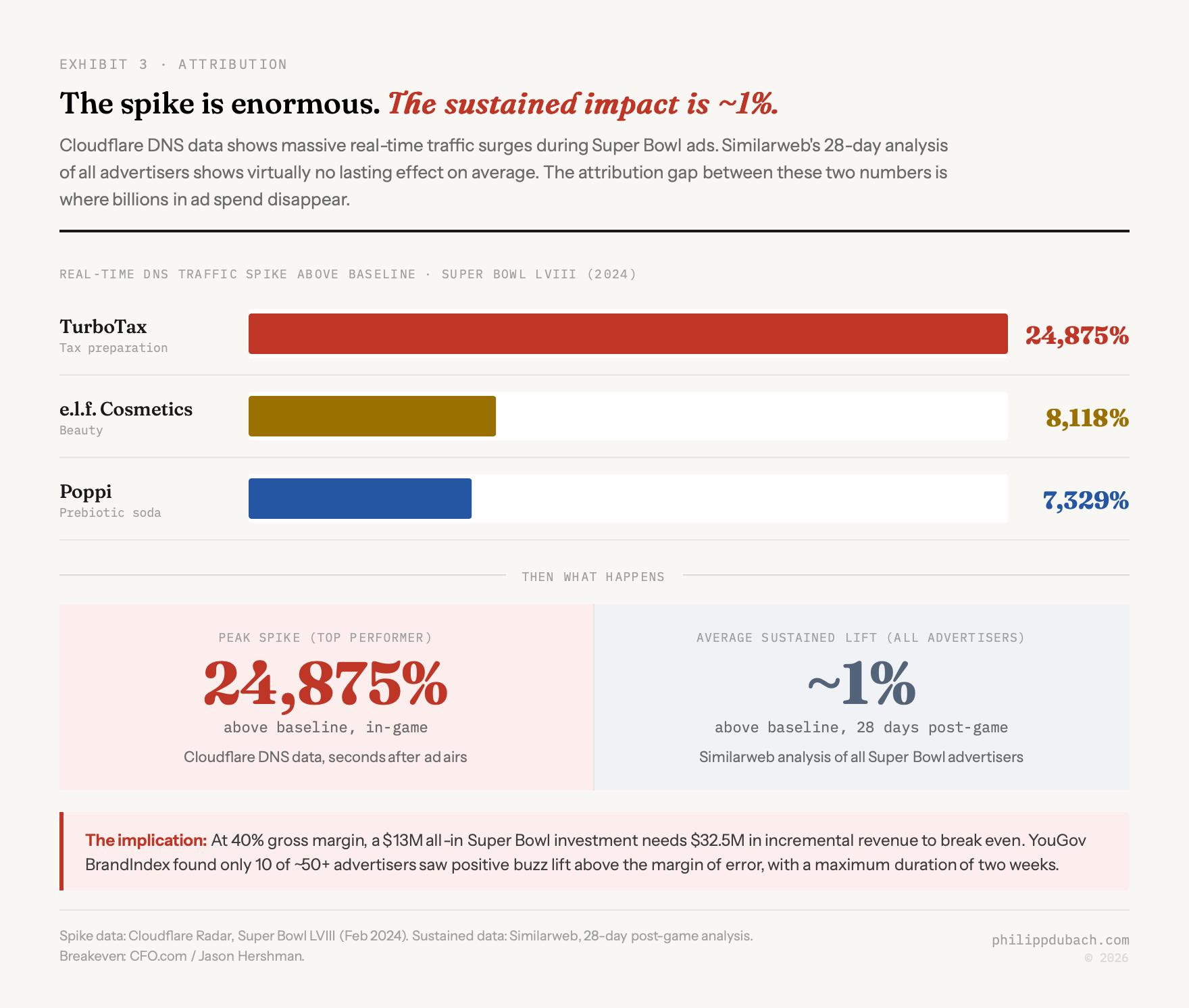

Cloudflare’s DNS data showed TurboTax saw a 24,875% traffic increase above baseline after its 2024 Super Bowl ad. e.l.f. Cosmetics saw 8,118%. Poppi saw 7,329%. But a Similarweb analysis of 28-day post-game traffic found an average increase of only ~1% across all advertisers. The spike is enormous and ephemeral. YouGov BrandIndex found that only 10 of roughly 50+ advertisers saw positive buzz lift above the margin of error, with a maximum duration of two weeks.

CFO.com’s Hershman offered the most useful framing for anyone trying to evaluate this honestly: marketing will come back with impressions, social mentions, and “earned media value,” which he described as Wall Street’s least favorite made-up metric. The only meaningful number is incremental contribution profit. At 40% gross margin, a $13 million all-in Super Bowl investment needs $32.5 million in incremental revenue just to break even on pure acquisition economics.

The NFL’s advertising pricing machine

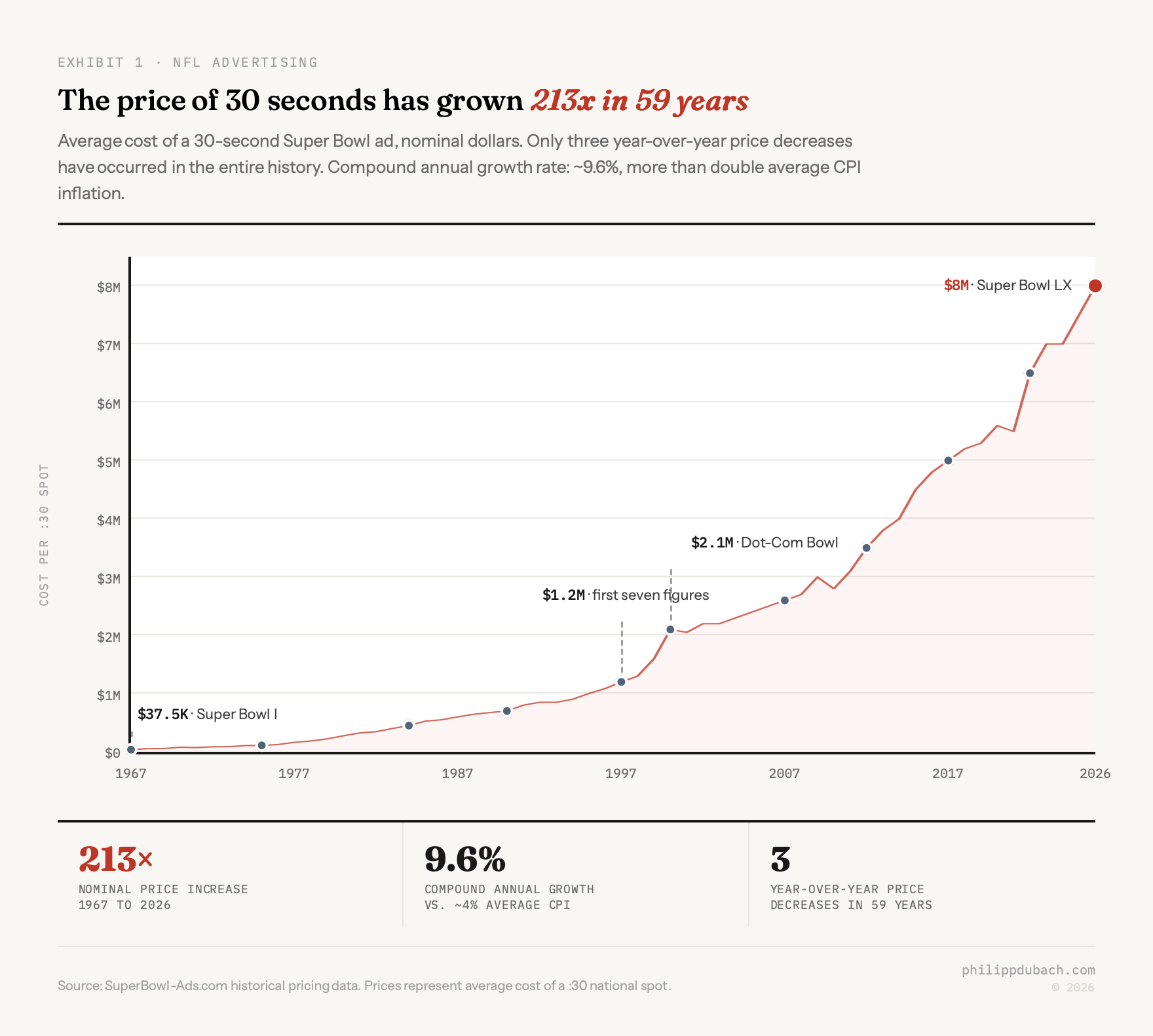

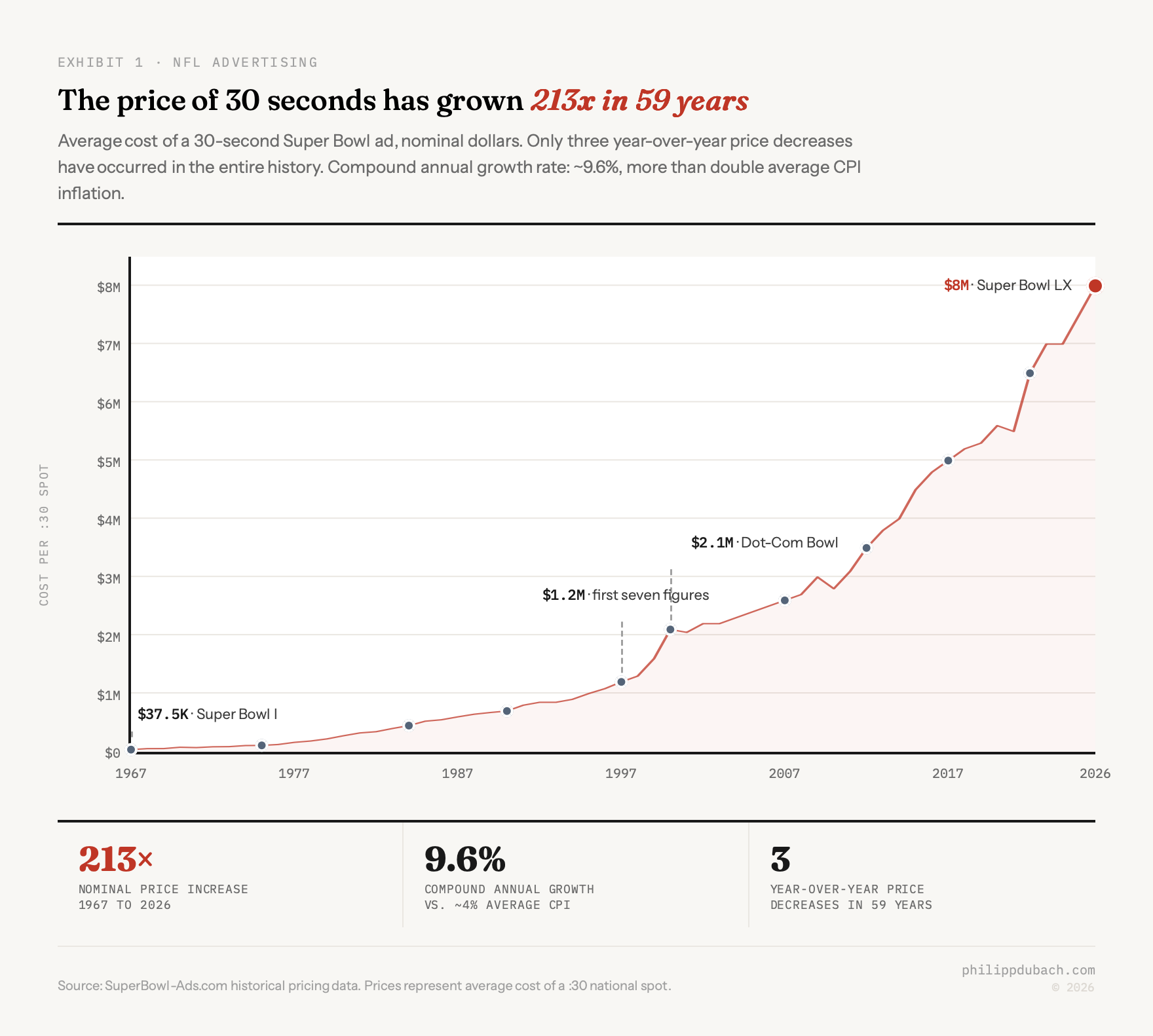

The NFL doesn’t just sell advertising inventory. It operates the most effective price-discrimination machine in American media. Super Bowl ad prices have increased from $37,500 in 1967 to $8 million in 2026, a 213x nominal increase and roughly 22–23x in real terms. The compound annual growth rate of approximately 9.6% is more than double average CPI inflation over the same period. Only three year-over-year price decreases have occurred in the entire 60-year history.

The NFL’s leverage comes from a structural scarcity that it actively maintains. Super Bowl ad inventory sells out months in advance. NBC sold out its 2026 inventory before the NFL season even started, with some companies paying $10 million or more due to what NBCUniversal’s Mike Marshall called “the marketplace demand.” Fox reported $800+ million in gross ad revenue from Super Bowl LIX in 2025, a record that industry analysts expect to become a billion dollars within two to three years. The mandatory companion buys force advertisers into additional network inventory they might not otherwise purchase, extracting surplus beyond the headline slot price.

Viewership has cooperated. The Super Bowl drew 51.2 million viewers in 1967 and 127.7 million in 2025. Streaming hasn’t fragmented the audience; it’s expanded it. Tubi alone delivered 13.6 million streaming viewers for Super Bowl LIX, a 94% increase over Fox’s previous Super Bowl. AdImpact data showed streaming at 49% of total viewership, up from 41.5% in 2024. The audience skews younger on streaming: Tubi’s Super Bowl audience was 38% more likely to be 18–34 than the overall game audience, which is exactly the demographic advertisers pay premiums to reach.

The result is a market where the seller has near-monopoly pricing power, the buyers face a prisoner’s dilemma that prevents collective resistance, and the audience keeps growing. The NFL has essentially created a Veblen good in advertising: the price itself signals legitimacy, which makes the price self-sustaining. The 2000 “Dot-Com Bowl” saw 14+ internet companies advertise, using the Super Bowl as a credibility play. At least eight went bust within a decade. The 2022 “Crypto Bowl” featured Coinbase, FTX, Crypto.com, and eToro spending a collective $54 million. FTX collapsed into bankruptcy within nine months. The pattern repeats because the mechanism works: bubble industries pay the premium precisely because appearing in the Super Bowl signals they belong among established brands. That this signal is often false doesn’t reduce its price.

The cases that define the genre

Apple’s “1984” ad cost approximately $750,000–$900,000 to produce plus $800,000 in airtime, roughly $4 million in today’s dollars. Apple’s board hated it and ordered the time sold back. Steve Jobs intervened. The ad generated $155 million in Macintosh sales within three months. Apple sold 250,000 Macs in the first year against a 30,000-unit break-even target. It sits in the Smithsonian.

Coinbase’s 2022 QR code ad cost $14 million for 60 seconds of a bouncing QR code on a black screen. The landing page received 20+ million hits in one minute, crashing the app. Downloads surged 309% week-over-week. The ad won the Clio “Super Clio” and finished dead last in USA Today’s Ad Meter consumer rankings simultaneously. Then the crypto market collapsed, Coinbase laid off 18% of staff, and the massive awareness evaporated. A reminder that advertising cannot fix a product’s relationship to reality.

GoDaddy advertised in every Super Bowl from 2005 to 2015, deliberately courting controversy with provocative ads. Their first appearance generated a 378% website traffic spike and 51.4% share of voice among all advertisers, largely because Fox pulled the second airing and created a news cycle. Today over 60% of visitors go to GoDaddy.com directly rather than through search. The company grew to 21 million customers before going public. Provocation as a launch strategy worked, until the brand matured and pivoted away.

System1 data offers a sobering counterpoint to these highlights: 21% of viewers in 2025 couldn’t recall which brand was behind the ad they’d just watched. That means roughly one in five Super Bowl ads converts millions in ad spend into brandless entertainment. The audience enjoyed the show. They just have no idea who paid for it.

What the economics of a Super Bowl ad tell us

I keep coming back to Hartmann and Klapper’s central result because it’s the one that reshapes how you think about the entire exercise. The Super Bowl ad works brilliantly as an investment, but only when the advertiser has category exclusivity. The moment a competitor shows up, the gains evaporate. What looks like an advertising problem is actually a competitive strategy problem.

Anheuser-Busch paid for exclusivity for 33 years because the company understood this. The $278 million over a decade wasn’t a media buy. It was an entry barrier. The moment that barrier fell in 2023, the category filled with nine competing brands and the collective value of Super Bowl beer advertising almost certainly declined. The NFL captured the difference.

This means the honest answer to “should you buy a Super Bowl ad?” isn’t about CPMs or brand lift or even ROI in the traditional sense. It’s about whether your competitive position allows you to capture the value or whether you’re paying for a prisoner’s dilemma that the NFL designed.

Reitano’s asymmetric upside thesis is logically sound for a company like Ro, which was advertising in a healthcare category without heavy Super Bowl competition and used the spot as a genuine brand awareness play. But the framework breaks down when applied generally. The 2026 Super Bowl featured Novo Nordisk, Ro, Hims & Hers, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Eli Lilly all running health-related ads. Northwestern’s Tim Calkins called it the “GLP-1 Super Bowl.” If the Hartmann-Klapper result holds across categories, those brands collectively spent north of $100 million on ads whose effects substantially cancelled each other out.