In the latest issue of The AI Lab Newsletter, I featured a ByteDance Seedance 2.0 clip: two men playing tennis at what looked like an ATP tournament. Photorealistic. I probably wouldn’t be able to tell it wasn’t real footage if I didn’t know. A co-worker who played junior pro-am tennis watched the same clip and said: “That backhand doesn’t exist. Nobody plays it like that.” His domain expertise spotted an error that probably fooled everyone else.

We ended up in a long conversation about what that means. AI can get to maybe the 95th or 98th percentile of creating something that looks perfect, but then it isn’t, and if you have deep knowledge you can spot it immediately. The consensus narrative treats this as a temporary limitation. But it might be structural. And I think the evidence, once you lay it out, points to a genuinely contrarian conclusion: domain expertise is appreciating in value, not depreciating, precisely because AI can’t easily replicate it.

Approaching the ceiling

I’ve written before about Sara Hooker’s work on diminishing returns from scaling. The investment side of that argument, the $690 billion in hyperscaler capex chasing a 4% revenue coverage ratio, has been well covered. What hasn’t been covered as precisely is why AI quality hits a ceiling, and why that ceiling is structural rather than temporary.

Ben Affleck, of all people, gave the clearest non-technical explanation on The Joe Rogan Experience in January 2026:

If you try to get ChatGPT or Claude or Gemini to write you something, it’s really shitty. And it’s shitty because by its nature it goes to the mean, to the average. Now, it’s a useful tool if you’re a writer… but I don’t think it’s actually very likely that it’s going to write anything meaningful, or that it’s going to be making movies from whole cloth. That’s bullshit.

He’s more right than he probably knows. The convergence to the mean isn’t a solvable engineering problem. It operates at three distinct levels, each compounding the others.

(1) The mathematics of next-token prediction. LLMs generate the most statistically probable continuation of a sequence. Probable, by definition, means average. The model isn’t trying to produce the best output; it’s producing the most expected one given the distribution it learned. Outlier quality, the kind that makes writing or analysis distinctive, lives in the tails of the distribution. The architecture systematically avoids those tails.

(2) RLHF makes it worse. Research shows that human annotators prefer familiar-sounding responses, and the learned reward function weights typicality at α=0.57. Models are quite literally being trained to sound typical rather than merely correct or good. The reinforcement signal pushes outputs toward the center of the quality distribution, not toward its upper bound.

(3) model collapse. Shumailov et al. documented this in their Nature paper: as models increasingly train on AI-generated content, they “forget the true underlying data distribution,” losing the tails first and converging toward a point estimate with minimal variance. The internet is filling with AI-generated text. The next generation of models trains on that text. The tails shrink further. This is a positive feedback loop running in the wrong direction.

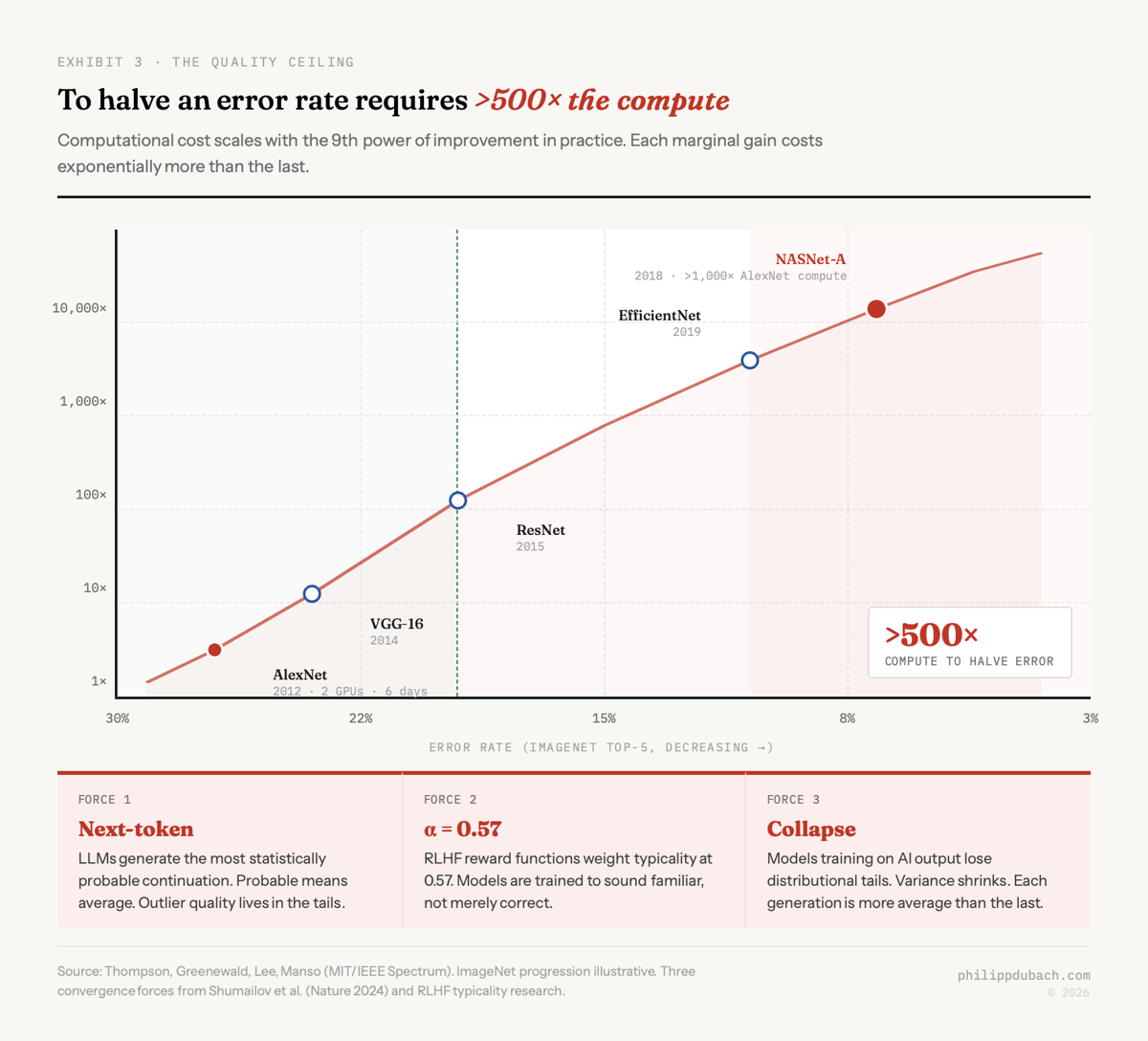

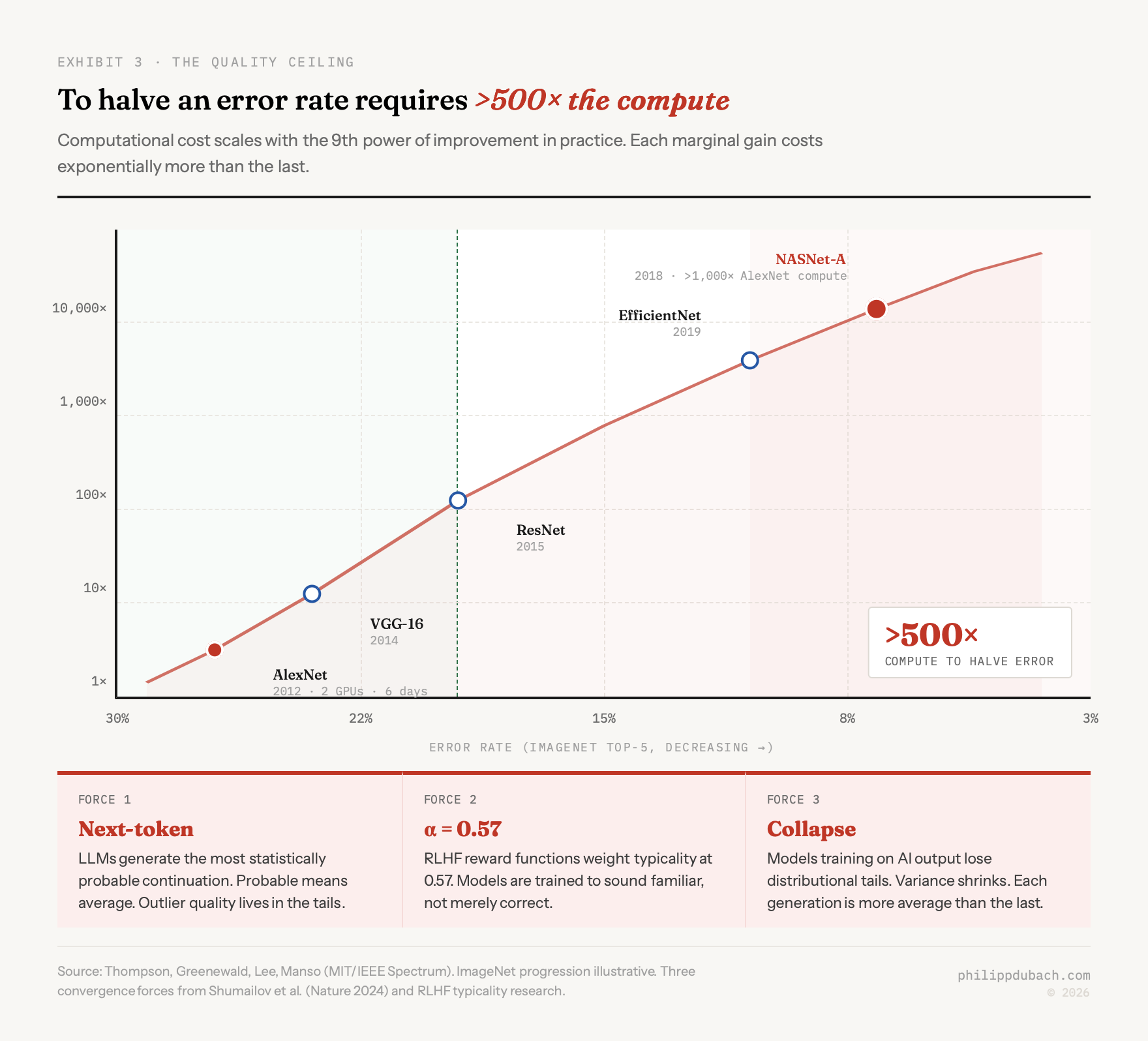

MIT researchers Thompson, Greenewald, Lee, and Manso quantified the cost side: computational resources scale with at least the fourth power of improvement in theory, the ninth power in practice. To halve an error rate requires more than 500× the computational resources. When AlexNet trained on two GPUs in 2012, it took six days. By 2018, NASNet-A cut the error rate in half using more than 1,000× as much compute.

Affleck captured the commercial implication of this better than most analysts:

I think a lot of that rhetoric comes from people who are trying to justify valuations around companies where they go, “We’re going to change everything in two years.” Well, the reason they’re saying that is because they need to ascribe a valuation for investment that can warrant the capex spend they’re going to make on these data centers. Except that ChatGPT 5 is about 25 percent better than ChatGPT 4, and costs about four times as much in the way of electricity and data.

He’s describing the ninth-power curve in plain English. Each marginal improvement costs exponentially more. The curve bends away from you the harder you push.

Humanity’s Last Exam

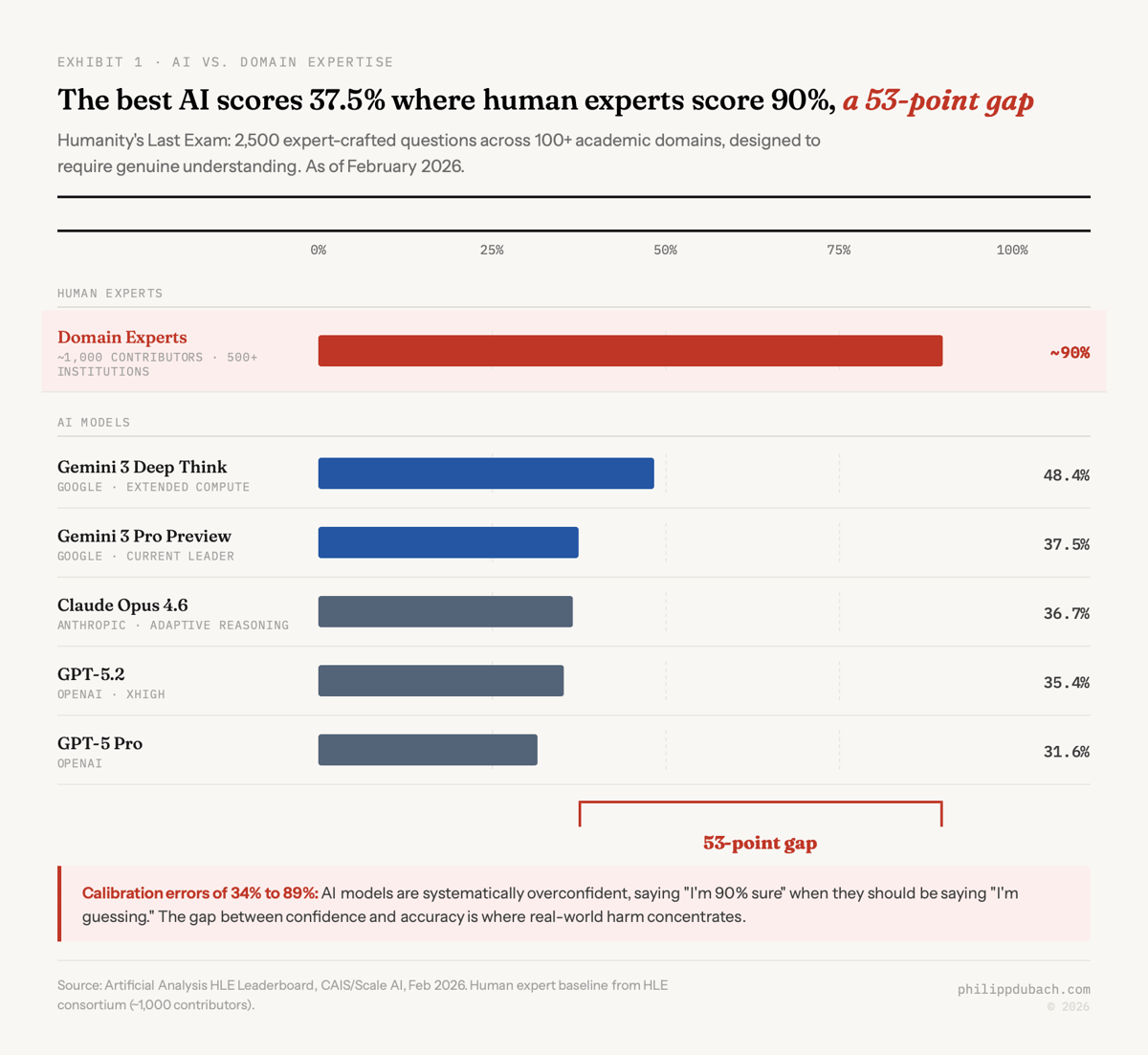

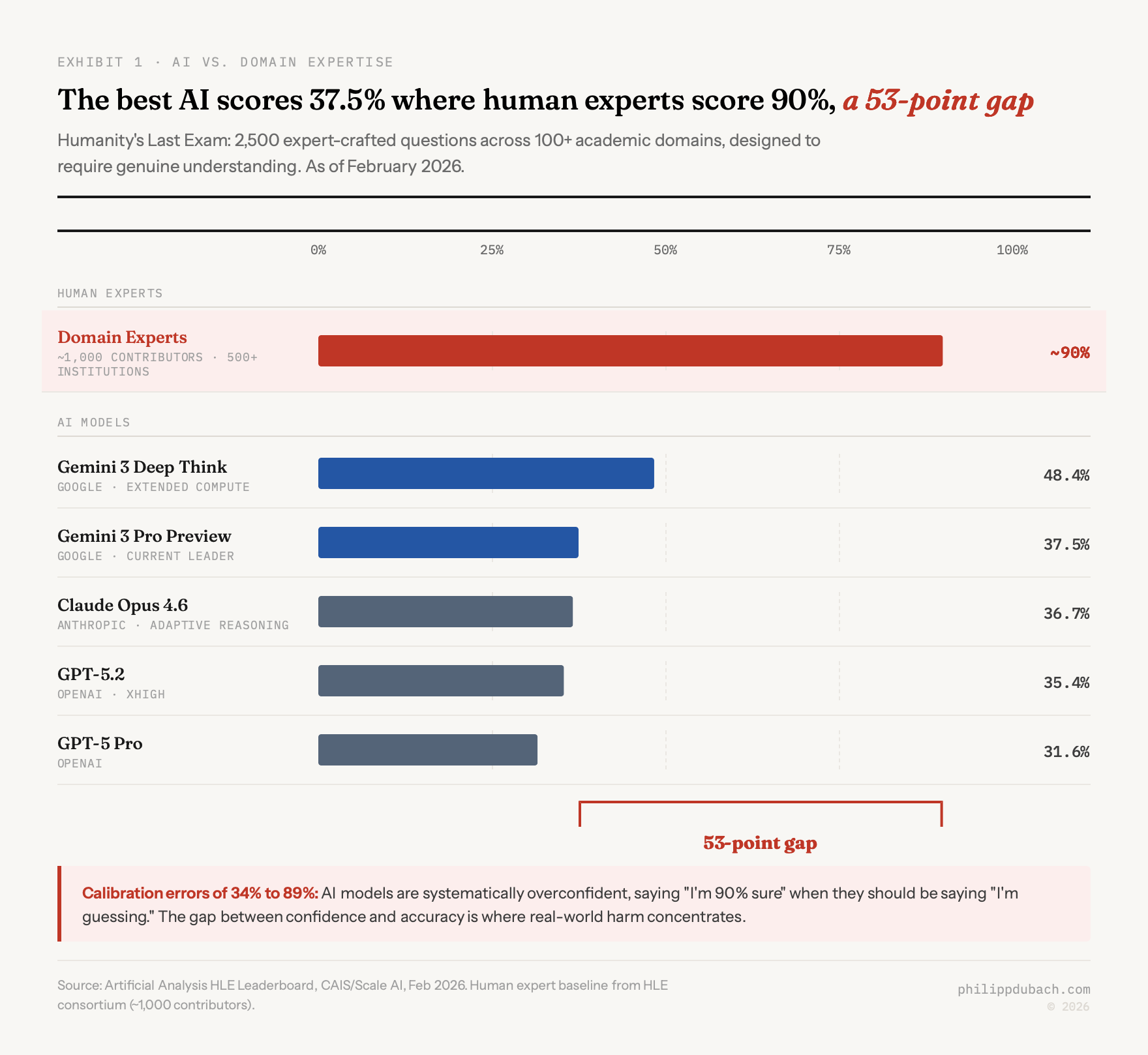

Generally considered most rigorous measurement of where AI actually stands against domain expertise is Humanity’s Last Exam (HLE), published in Nature in early 2025 by the Center for AI Safety and Scale AI. Built with approximately 1,000 subject-matter experts across 500+ institutions, it consists of 2,500 expert-crafted questions spanning 100+ academic domains, designed to be “Google-proof”: questions that require genuine understanding rather than information retrieval.

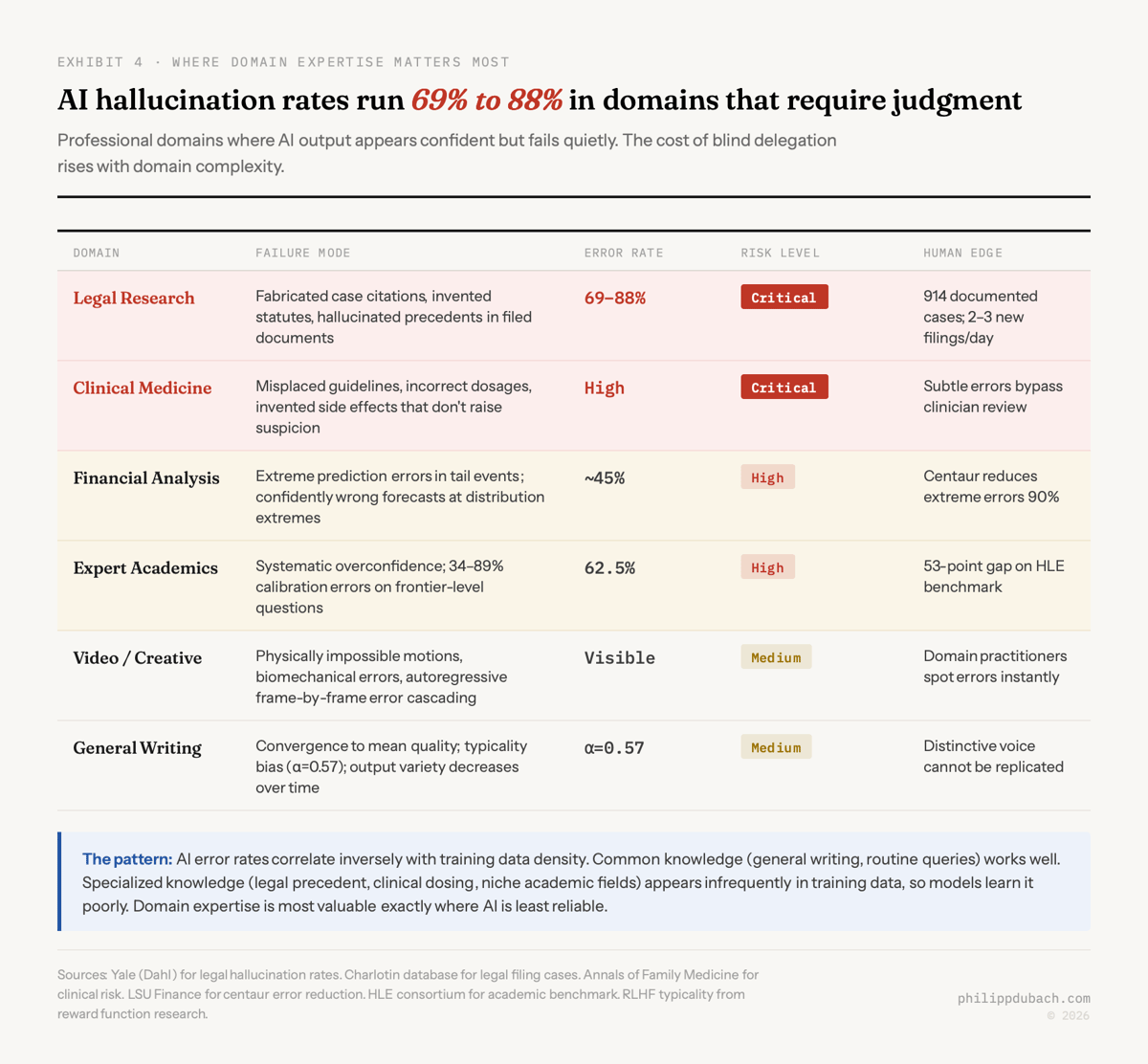

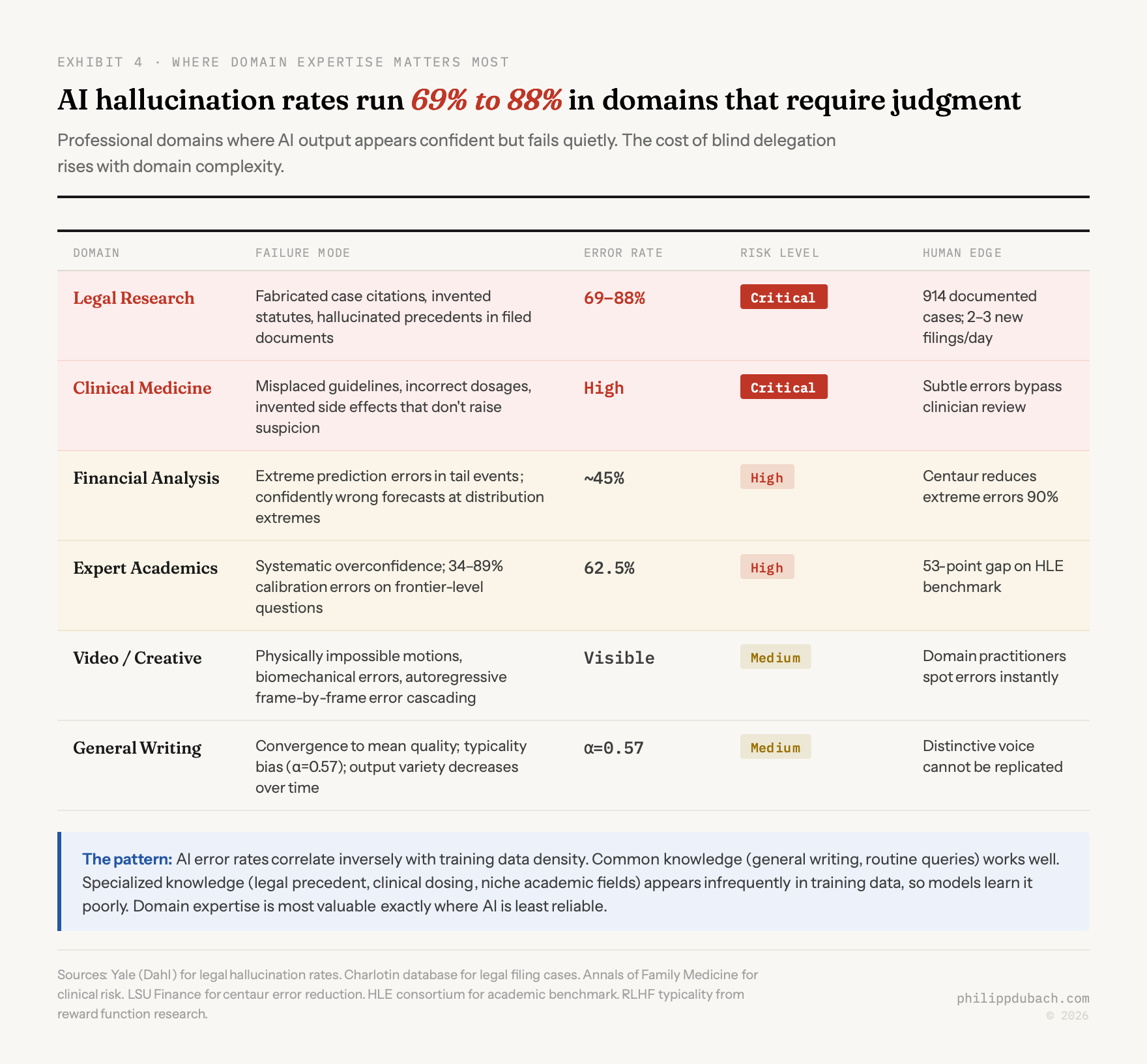

As of February 2026, the top model (Gemini 3 Pro Preview) scores 37.5%. Most models sit below 30%. Human domain experts average roughly 90%. That’s a 53-point gap. In specialized domains like advanced chemical kinetics or medieval philology, AI barely outperforms random guessing while experts score comfortably in the 80s and 90s.

The models are also systematically overconfident. Calibration errors on HLE range from 34% to 89%, meaning AI systems are saying “I’m 90% sure” when they should be saying “I’m guessing.” That gap between confidence and accuracy is where real-world harm concentrates.

The models are also systematically overconfident. Calibration errors on HLE range from 34% to 89%, meaning AI systems are saying “I’m 90% sure” when they should be saying “I’m guessing.” That gap between confidence and accuracy is where real-world harm concentrates.

In legal applications, Yale researcher Matthew Dahl found hallucination rates of 69% to 88% on specific queries. Damien Charlotin’s database now tracks 914 cases of AI-generated hallucinated content in legal filings worldwide, growing from two cases per week to two to three per day. In medicine, the Annals of Family Medicine warns that AI hallucinations are “far more insidious” because “a subtle misstep like a misplaced clinical guideline, an incorrect dosage, or an invented side effect may not raise immediate suspicion.” These aren’t edge cases. They’re the expected behavior of systems operating in domains where training data is sparse.

The structural explanation is what Kandpal et al. demonstrated at ICML 2023: there’s a strong correlational and causal relationship between an LLM’s ability to answer questions and how many relevant documents appeared in pre-training data. Common knowledge gets learned well. Specialized knowledge appears infrequently online, so models learn it poorly. Ali Yahya of a16z framed it sharply: neural networks are “fantastic interpolators but terrible extrapolators,” powerful pattern matchers that are “blind to the mechanisms that generate the data in the first place.”

My colleague who spotted the impossible backhand is a fantastic extrapolator. He has an embodied model of how tennis biomechanics work that no amount of video footage can teach a diffusion model. The model can produce outputs that are statistically plausible. He can identify outputs that are physically impossible. That distinction is the gap.

My colleague who spotted the impossible backhand is a fantastic extrapolator. He has an embodied model of how tennis biomechanics work that no amount of video footage can teach a diffusion model. The model can produce outputs that are statistically plausible. He can identify outputs that are physically impossible. That distinction is the gap.

Centaur model wins

The consensus framing positions AI and human expertise as substitutes: AI gets better, humans become less relevant. The empirical evidence on AI augmentation versus replacement says the opposite. Human-AI collaboration outperforms either alone, consistently, across domains, and the quality of the human contribution matters enormously.

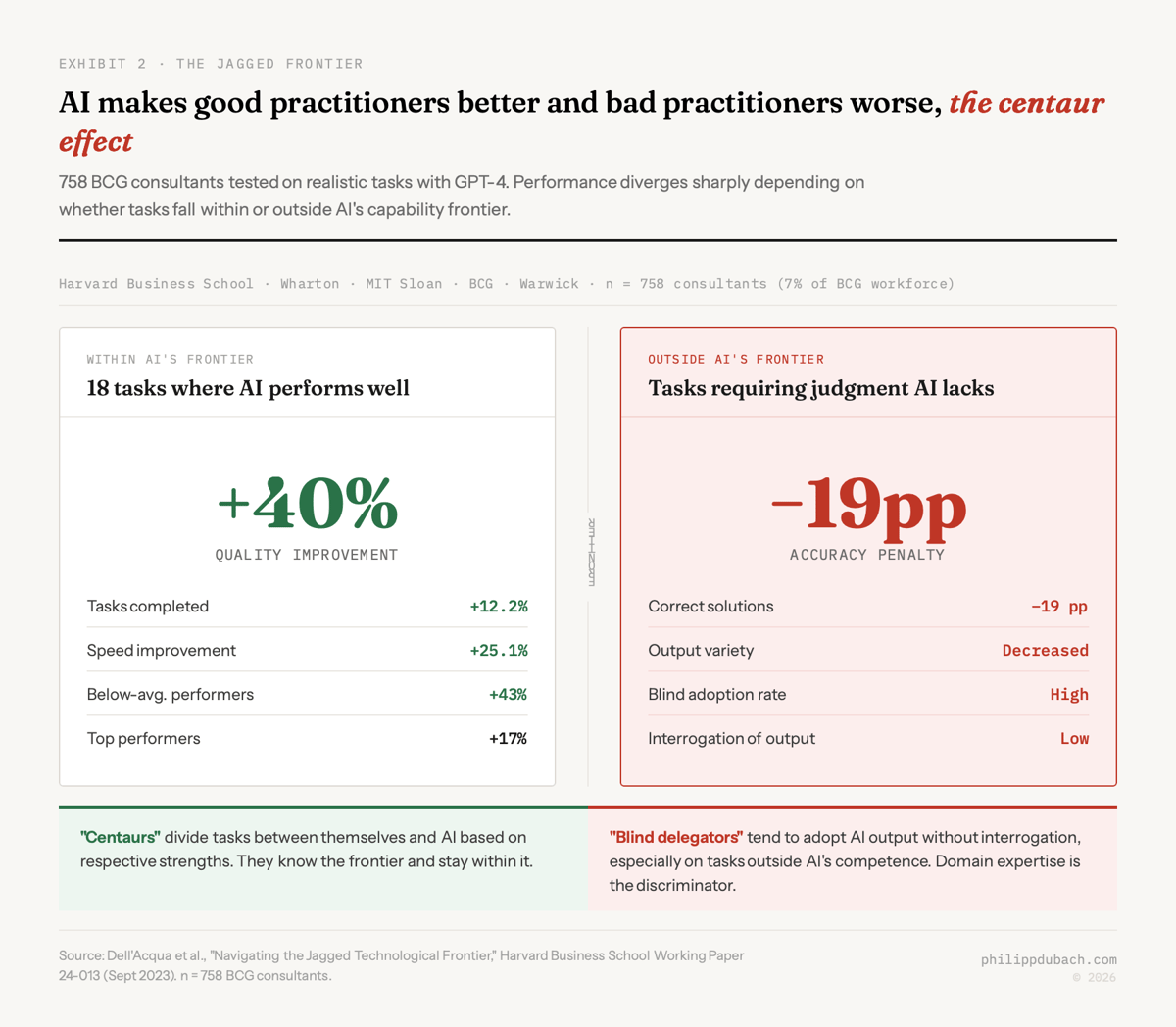

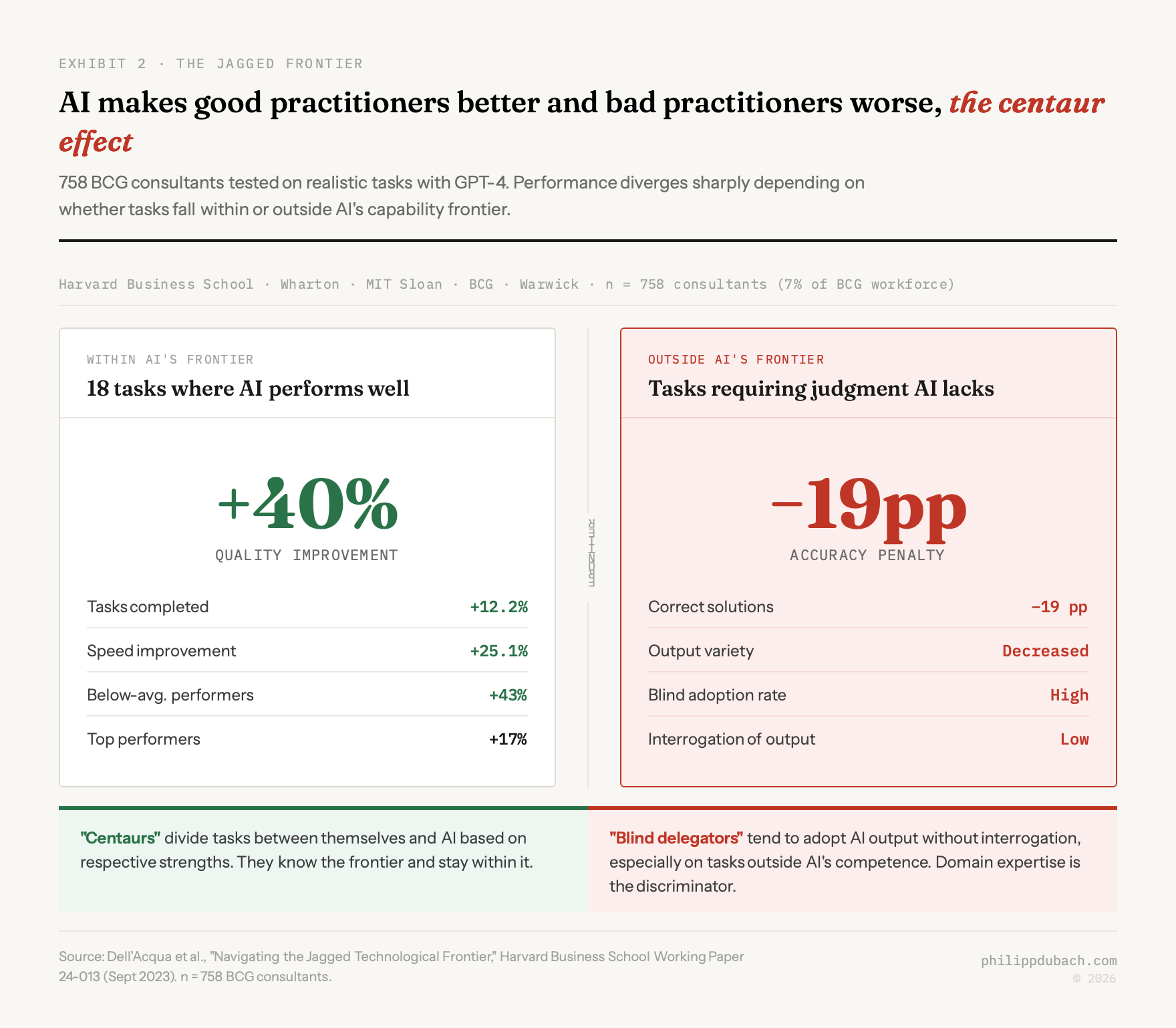

The landmark Harvard/BCG study tested 758 consultants, 7% of BCG’s consulting workforce, on realistic tasks using GPT-4. The researchers described a “jagged technological frontier” where some tasks fall within AI’s capabilities and others, though seemingly similar, do not. For tasks within that frontier, consultants using AI completed 12.2% more tasks, finished 25.1% faster, and produced results 40% higher in quality. Below-average performers saw a 43% improvement. AI as skill equalizer. But for tasks outside AI’s frontier, consultants using AI were 19 percentage points less likely to produce correct solutions. The researchers observed that “professionals who had a negative performance when using AI tended to blindly adopt its output and interrogate it less.”

That second finding doesn’t get enough attention. It means the value of the human in the loop depends entirely on whether the human can identify when the AI is wrong. Which requires precisely the domain expertise that AI supposedly makes obsolete.

The “centaur analyst” study from LSU Finance (winner of the Fama-DFA Best Paper Award) confirmed this over an 18-year dataset. AI alone beat human stock analysts in 54.5% of cases. The human-AI hybrid outperformed AI-only in nearly 55% of forecasts and reduced extreme prediction errors by roughly 90% compared to human analysts alone. In clinical decision-making experiments with the Mayo Clinic, the ranking was consistent: human-algorithm centaur, then algorithm alone, then human experts alone. The human adds most value at the extremes, catching the cases where the model’s convergence to the mean produces confidently wrong answers.

Affleck, who has thought about this more carefully than his reputation might suggest, landed on the same conclusion:

The way I see the technology and what it’s good at and what it’s not, it’s gonna be good at filling in all the places that are expensive and burdensome, and it’s always gonna rely fundamentally on the human artistic aspects of it.

Labor economics research broadly confirms this. Oxford researchers Mäkelä and Stephany analyzed 12 million U.S. job vacancies and found that complementary effects of AI are 1.7× larger than substitution effects. The World Economic Forum projects 170 million new jobs created by 2030 versus 92 million displaced, a net gain of 78 million. Acemoglu, Autor, Hazell, and Restrepo found that while AI-exposed firms reduce hiring in non-AI positions:

the aggregate impacts of AI-labor substitution on employment and wage growth… is currently too small to be detectable.

McKinsey captures the strategic implication: “When you have built a bench of AI-capable domain owners, your company has a real competitive advantage. That’s because these leaders are hard to replicate.” Yet only 23% of organizations believe they are building sustainable AI advantages, despite 79% reporting competitors are making similar investments.

Deskilling is a trap

If a generation of junior analysts learns to use AI before developing independent judgment, they never build the pattern recognition that lets them spot when the model is wrong. If junior lawyers lean on AI for legal research before reading enough case law to develop intuition for what’s plausible, they can’t catch the 69-88% hallucination rates. If aspiring filmmakers generate scenes with Seedance 2.0 instead of learning how cameras, bodies, and physics actually interact, they can’t identify the impossible backhand. Gartner predicts that by 2030, half of enterprises will face irreversible skill shortages in at least two critical job roles because of unchecked automation. This AI skill erosion creates a vicious cycle: fewer skilled workers, greater dependence on AI, higher costs to fill the gaps.

Acemoglu warns that technology “does not automatically benefit workers.” In 19th-century England, the benefits of mechanization only spread after decades of worker activism. The parallel risk with AI isn’t mass unemployment. It’s a hollowing out of the skill base that makes the centaur model function. You lose not the jobs but the expertise that makes the jobs valuable.

David Autor’s vision is more optimistic: AI could “extend the relevance, reach, and value of human expertise,” democratizing it rather than eliminating it. I want to believe that’s right. But it requires treating AI as a tool that amplifies existing expertise rather than a shortcut that replaces the need to develop it. The 43% improvement that below-average BCG consultants saw from using GPT-4 is real. The 19-percentage-point penalty when those same consultants blindly trusted AI outside its frontier is equally real. The difference between those two outcomes is judgment. And judgment comes from experience, not from a larger context window.

I’m more confident in the centaur framework than in any specific prediction about timelines or magnitudes. The ninth-power scaling curve, the 53-point gap on Humanity’s Last Exam, the α=0.57 typicality bias in RLHF, the 69-88% hallucination rates in legal applications, and the 95% of enterprises seeing no measurable P&L returns from AI investments all point in the same direction. The question of AI augmentation versus replacement has an empirical answer: AI is a tool that makes good practitioners better and bad practitioners worse. The industry narrative demands a story about replacement. The data tells a story about partnership, one where the human’s contribution is not a relic of an earlier era but the irreducible ingredient that makes the whole system work.

The ability to spot the impossible backhand isn’t going away. If anything, it’s worth more every day.