The real value of tail hedging is not in the hedge itself. It’s in what the hedge enables.

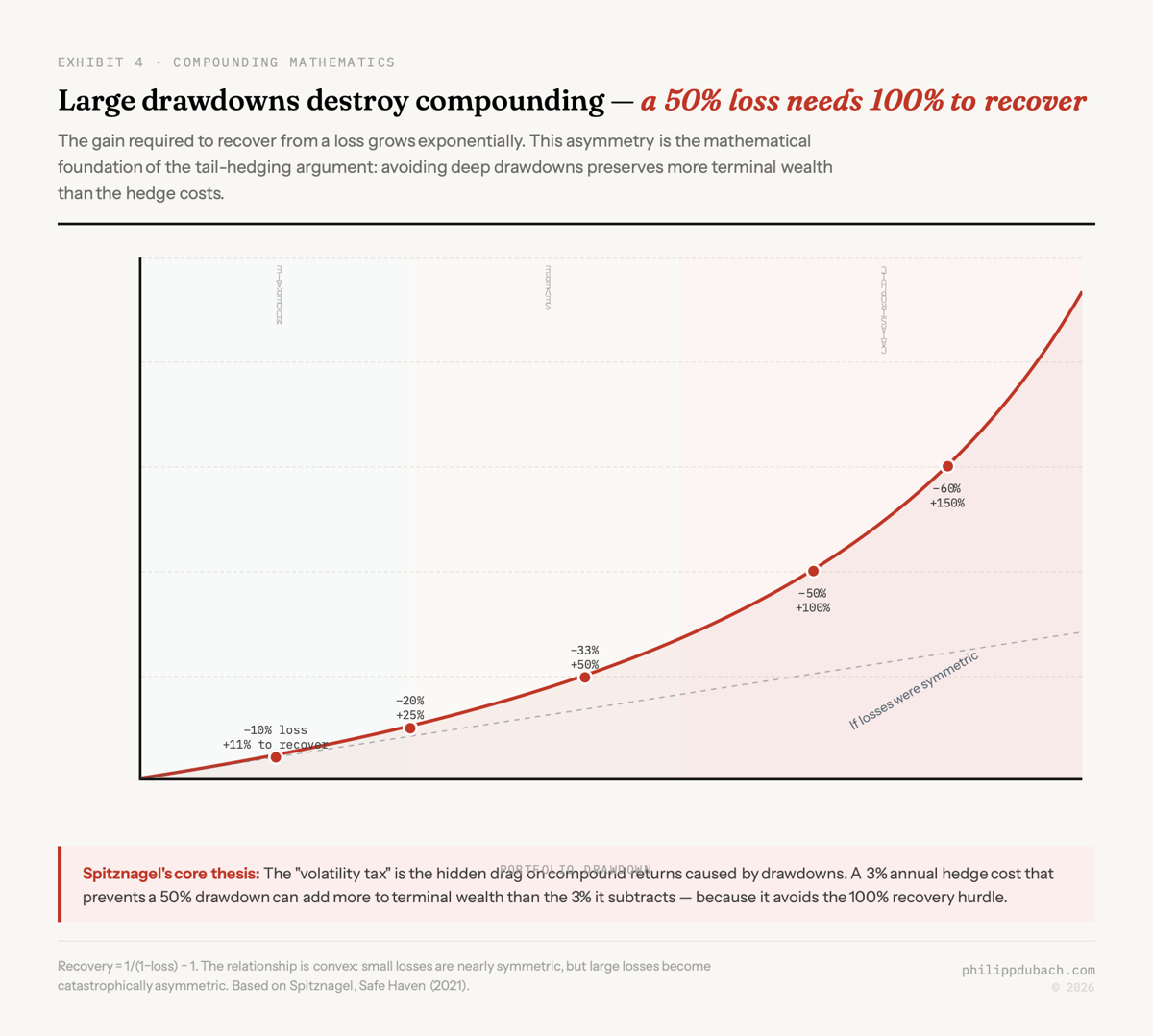

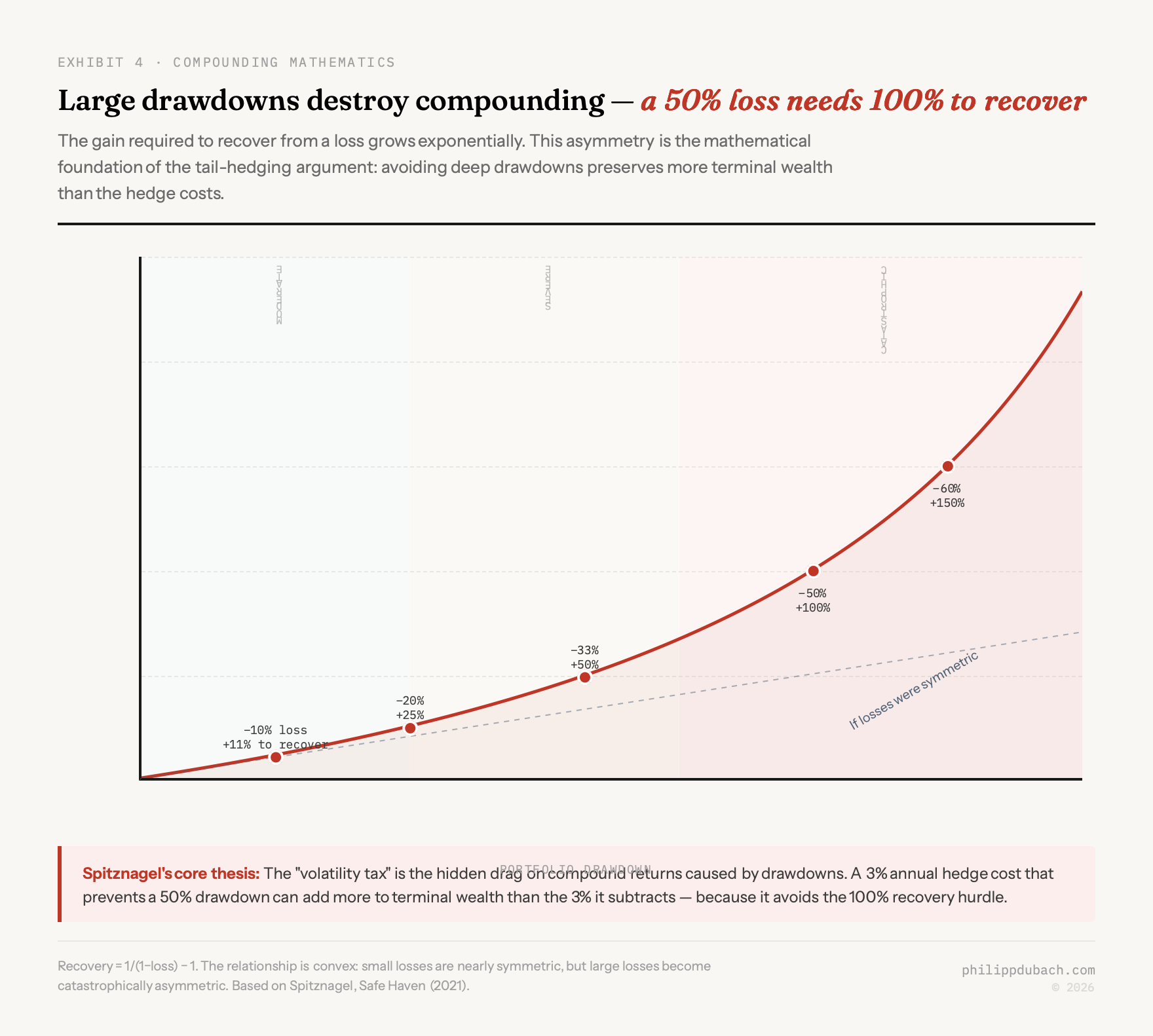

In The Variance Tax I wrote about the ½σ² formula: compound returns equal arithmetic returns minus half the variance, and because the penalty is quadratic, large drawdowns destroy wealth in ways that are hard to recover from. A portfolio that falls 50% needs 100% just to break even. That piece was about the problem. This one is about a potential solution, and about whether paying for crash protection can actually improve total returns rather than drag them.

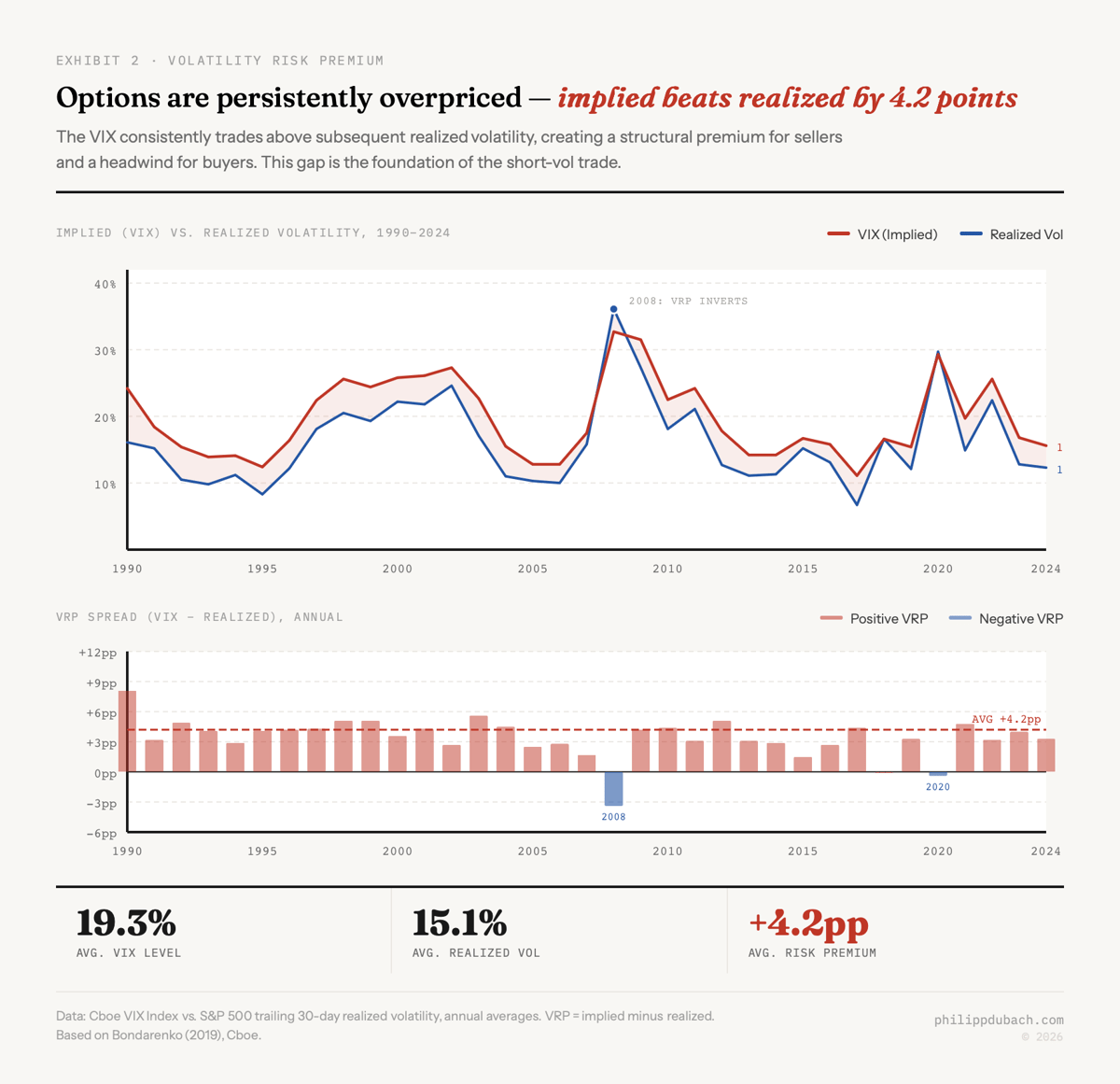

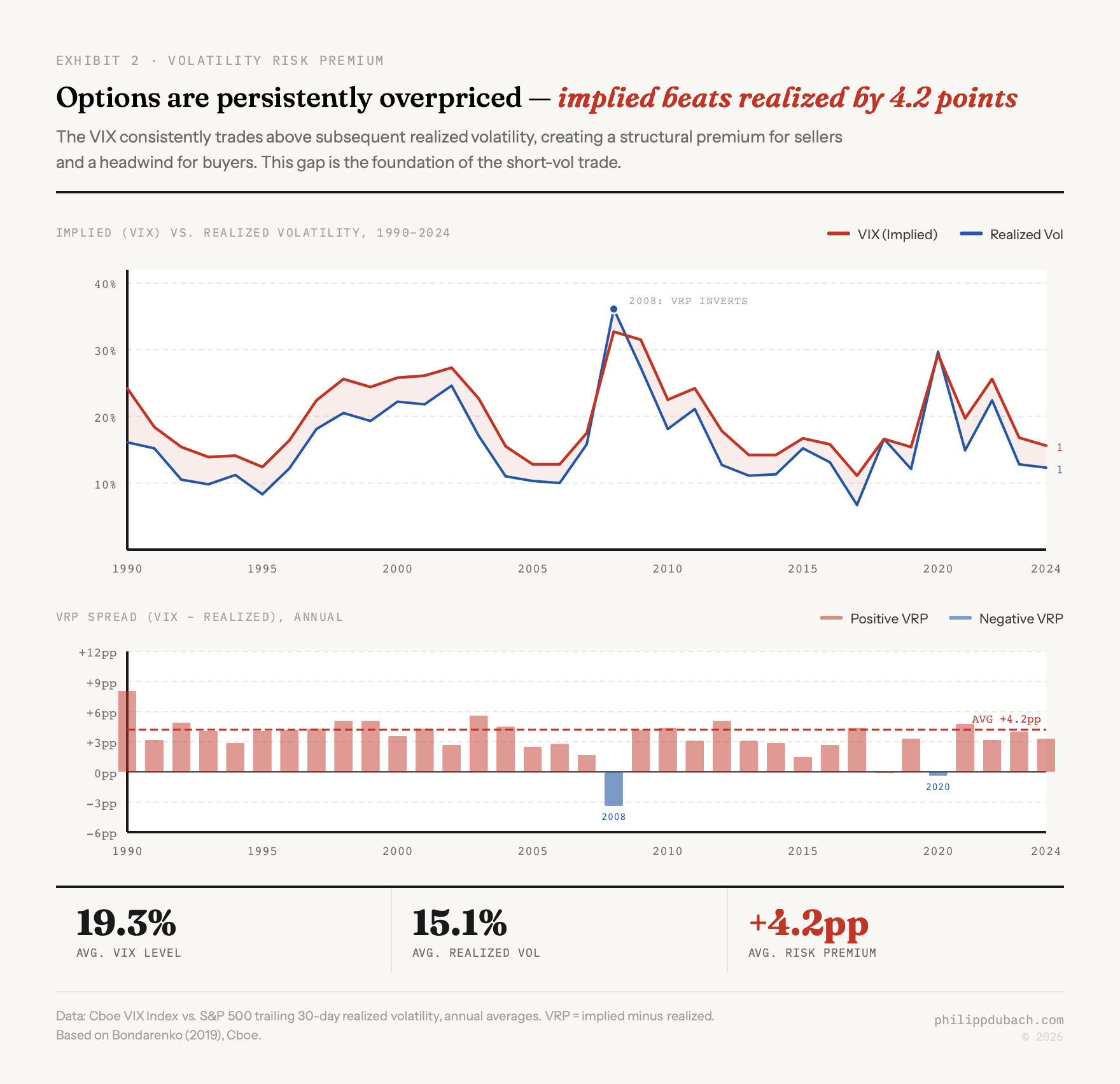

There is a chart circulating in quantitative finance circles that should not exist. It shows a strategy that buys put options on the S&P 500 and, when layered on top of a stock portfolio, improves total returns while simultaneously reducing volatility and maximum drawdown. The chart comes from Patrick Causley at One River Asset Management in a paper called “Heretical Thinking: The Long Volatility Premium” and it makes a specific claim: that long volatility, properly constructed, is not a cost center but a compensated factor that deserves to sit alongside value, momentum, and trend in institutional portfolios.

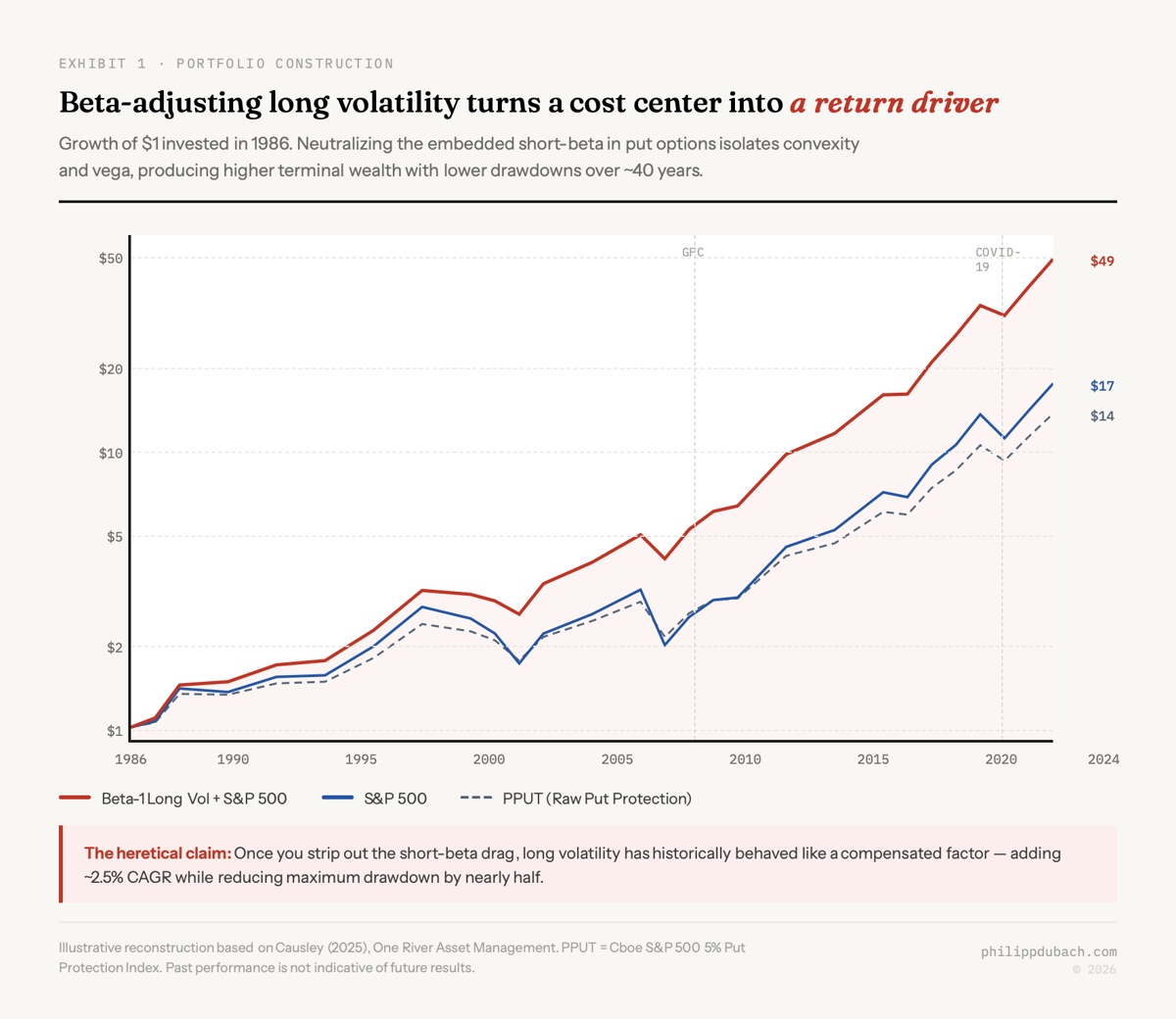

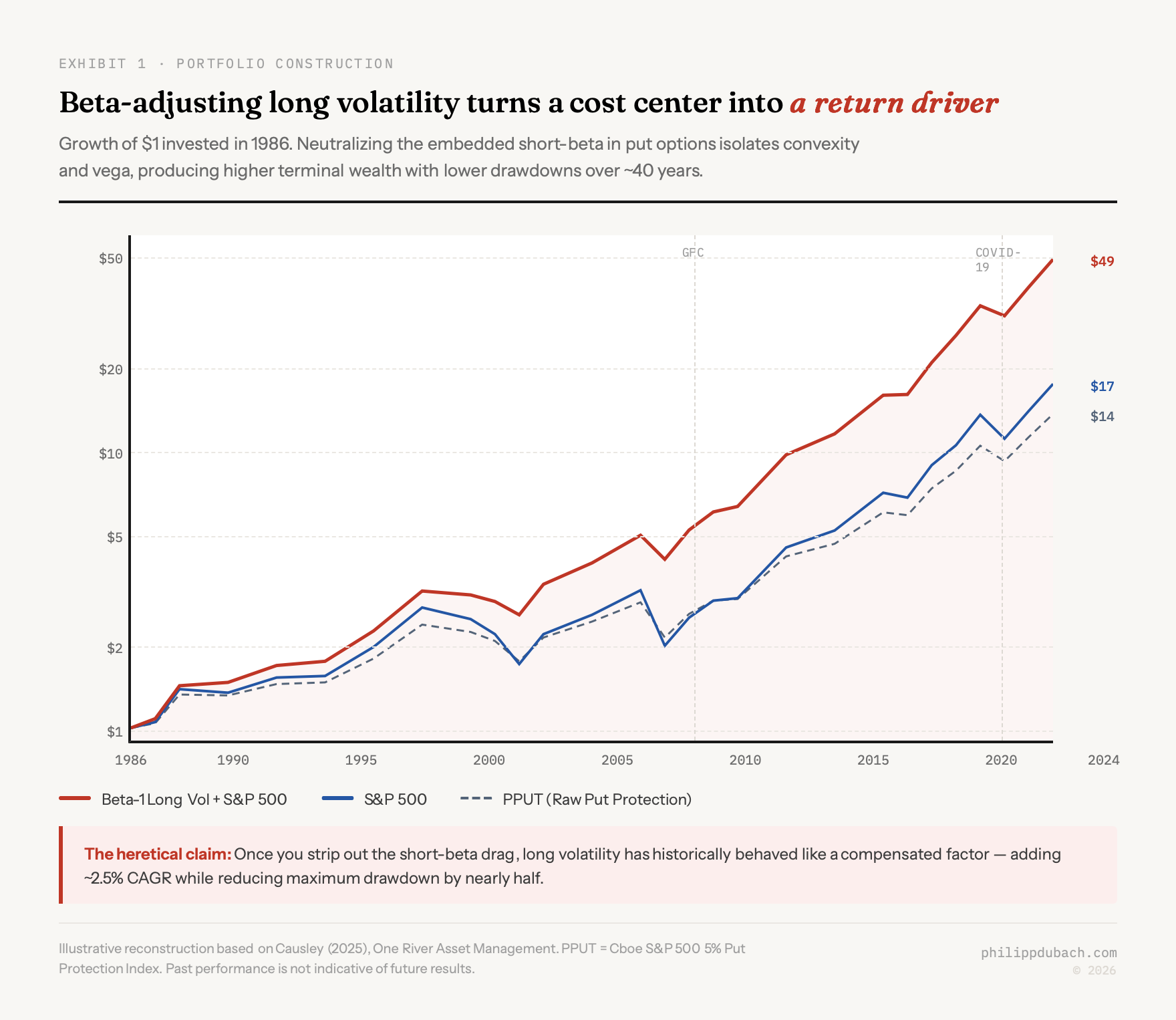

The conventional wisdom says buying puts is a losing game. The dominant empirical finding is that a volatility risk premium (VRP) exists: from 1990 to 2018, the average VIX level was 19.3% while average realized S&P 500 volatility was just 15.1%, a persistent gap of 4.2 percentage points. Options are, on average, overpriced relative to what materializes. The CBOE S&P 500 PutWrite Index, which systematically sells S&P 500 puts against cash collateral, rose 1,835% from 1986 to 2018. The CBOE 5% Put Protection Index, which buys puts as a hedge, rose only 708%. As Bondarenko (2019) documented, the PUT Index achieved 9.54% annualized versus 9.80% for the S&P 500 but with far lower volatility (9.95% vs. 14.93%), yielding a Sharpe ratio of 0.65 versus 0.33 for put buyers.

So selling options earns money. Buying them bleeds money. That is the consensus. This article is about why that framing, while technically correct, misses something important.

I. Separating beta from convexity

The key insight from the One River paper is that the raw return of a put option conflates two partially independent components, and conflating them has led to a categorical error in how most allocators think about tail hedging.

When you buy a put, your P&L is driven by delta (directional exposure to the underlying), gamma (the acceleration of that exposure as the market moves), and vega (sensitivity to implied volatility). The problem with naively holding puts is that delta embeds a massive short-beta position. Since the equity risk premium is perhaps the most robust finding in all of finance, you are fighting a powerful headwind. Your puts bleed value every day the market does not crash, and that bleed overwhelms the occasional windfall when it does.

Causley’s move is straightforward. Neutralize the short-beta by adding enough long equity exposure to offset the embedded delta. What remains is a beta-neutral “long volatility factor” that isolates gamma and vega. Stack this on top of an equity program and the historical results over approximately 40 years are striking: the beta-1 portfolio with long volatility outperformed a portfolio without it while producing lower volatility and a shallower maximum drawdown.

The persistence of this phenomenon, even with a simplistic implementation using monthly 5% OTM puts from the CBOE’s PPUT index, is what makes the paper interesting rather than dismissible. A more sophisticated execution (better strike selection, dynamic sizing, multi-tenor rolls) would likely improve results further. But the baseline already makes the case.

The persistence of this phenomenon, even with a simplistic implementation using monthly 5% OTM puts from the CBOE’s PPUT index, is what makes the paper interesting rather than dismissible. A more sophisticated execution (better strike selection, dynamic sizing, multi-tenor rolls) would likely improve results further. But the baseline already makes the case.

II. Why would a long volatility premium exist?

If markets are efficient, a beta-adjusted long volatility position should not deliver a positive premium. Three mechanisms suggest why it might.

The first is the rebalancing premium. When you hold negatively correlated assets and rebalance systematically, you extract what the literature calls a “rebalancing bonus” where the geometric return exceeds the weighted average of individual arithmetic returns. Recent work in the Investment Analysts Journal formalizes this for tail hedging specifically. A long volatility position that delivers explosive gains during crashes and modest losses during calm markets, rebalanced against equities, creates a structural tailwind. You systematically sell the hedge at high prices after crashes and buy it back cheaply during calm, monetizing mean reversion.

The second is that stock-volatility correlation intensifies dramatically during crashes. When equities fall sharply, implied volatility does not just rise proportionally, it spikes exponentially. The hedge’s payoff is largest precisely when the portfolio most needs it. This convexity, once beta-adjusted, can more than compensate for the ongoing cost of the position.

The third is a supply-demand imbalance. Institutional investors are structurally short volatility in numerous ways: through equity ownership itself, through structured products with embedded short option positions, and through strategies that implicitly sell insurance (risk parity, short vol ETFs, pension de-risking). Meanwhile, the supply of long volatility is limited by behavioral challenges. As Jody Deio of Aearon Risk Advisors explains: “People don’t have the patience to wear these exposures for any long period of time. You’re happy being basically a wasting asset. And a wasting asset is nothing that any investment committee or client meeting wants to deal with.” This behavioral gap between the demand for protection and the willingness to supply it may create a structural premium for those who can withstand the psychology.

All three mechanisms connect back to the variance tax. The ½σ² drag on compound returns means that reducing drawdown severity has a nonlinear effect on terminal wealth. By truncating left-tail outcomes, even a costly hedge can increase compound wealth through the compounding channel alone.

III. What the research actually says

The claim that long volatility is a compensated factor runs against a large body of literature documenting the short volatility premium. But the two are not necessarily contradictory. They operate at different levels of analysis.

Research from Barclays found that while the VRP has positive equity market beta, it also has excess alpha above that beta exposure. A linear regression of the VRP against S&P 500 returns found a significant positive intercept of roughly 3.48 volatility points independent of equity market direction. This suggests that both buying and selling volatility can capture distinct premia depending on how the trade is structured and what exposures are isolated.

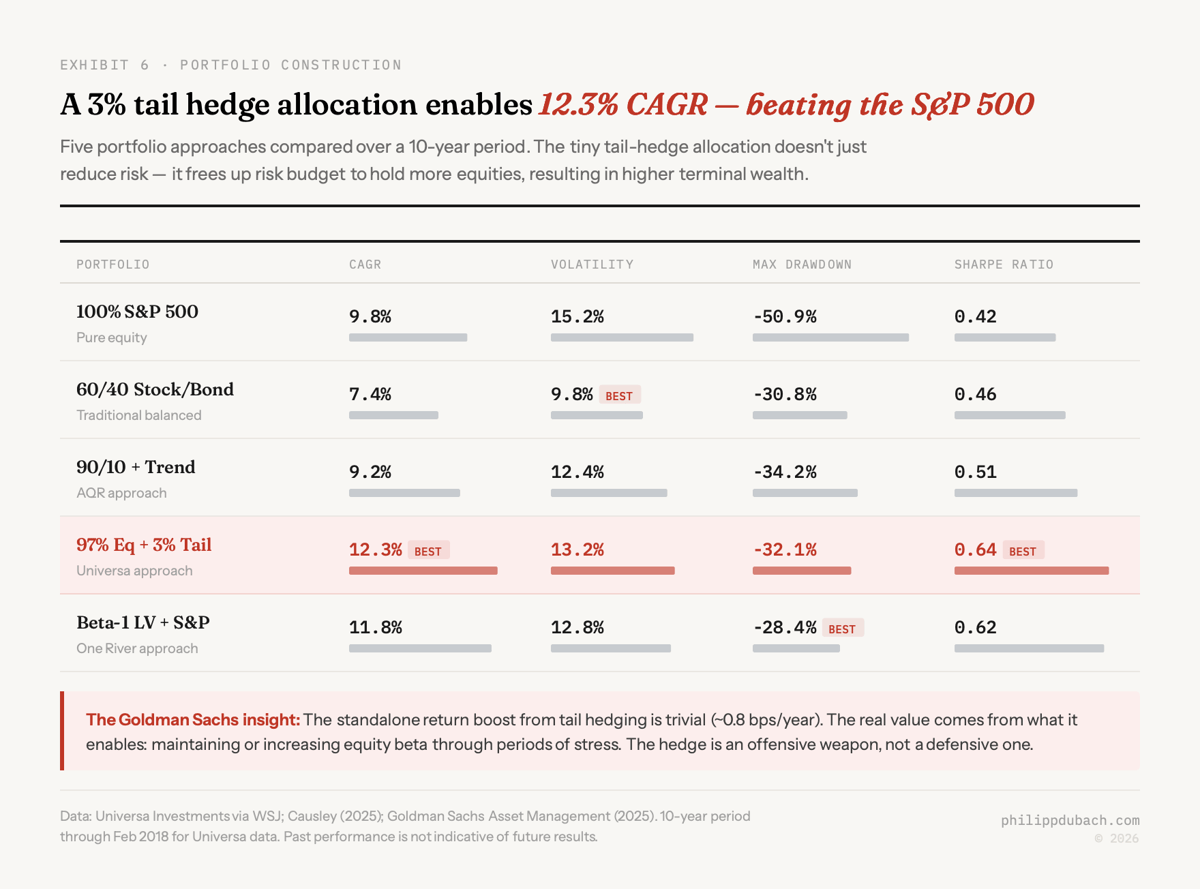

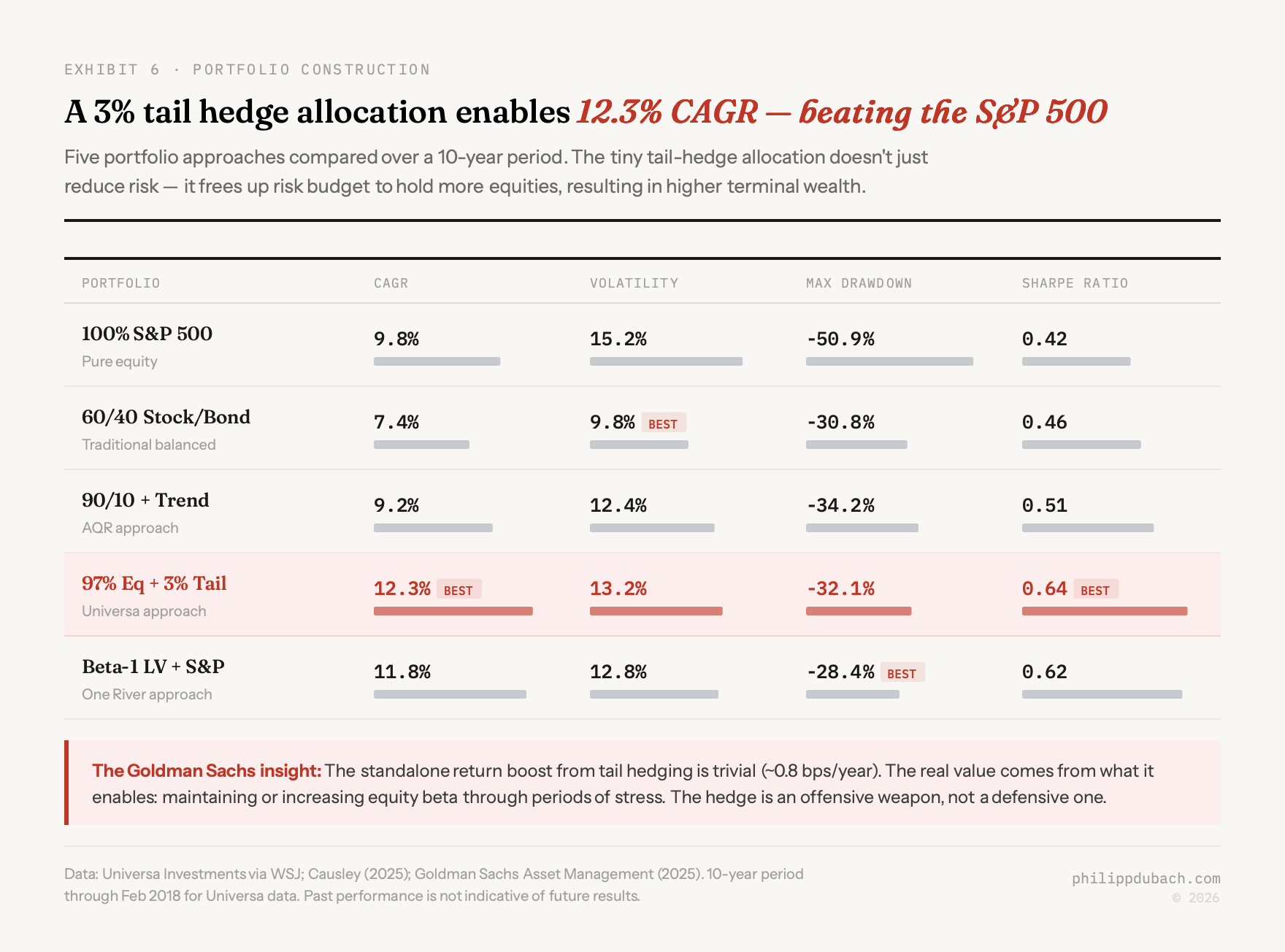

Goldman Sachs Asset Management’s 2025 analysis offers the most useful framing I have seen. Their key finding: even an idealized, 99% reliable tail-risk hedging strategy provides a standalone annual return boost of only about 0.8 basis points. Trivial. But that is not the point. The real value comes from what the hedge enables. Because tail-risk hedges reduce the impact of severe drops, they allow a portfolio to take on more equity risk, to increase beta. The gains from this “risk budget reallocation” can be substantial, especially for institutional investors with fixed drawdown constraints. In Goldman’s framing, tail-risk hedging is not a standalone return generator. It is an offensive weapon that enables more aggressive positioning in core assets. This is philosophically closer to how Formula 1 teams think about pit stops: they cost time, but soft tires allow faster laps, resulting in a faster overall race.

The numbers from Universa’s live track record add color. During Q1 2020, as the COVID pandemic triggered a 34% crash in the S&P 500, Universa delivered a 4,144% return. But Spitznagel himself downplays these headline figures, noting that “any punter can devise a trade that does well in a crash. The key is how you do in a crash relative to the rest of the time.” The Wall Street Journal reported that a strategy consisting of just a 3.3% allocation to Universa with the rest in the S&P 500 had a compound annual return of 12.3% over 10 years through February 2018, beating the S&P 500 itself. A 3.3% tail position improving total portfolio returns over a decade is not intuitive. But it follows directly from the variance tax arithmetic.

IV. Puts vs. trend: the tortoise and the hare

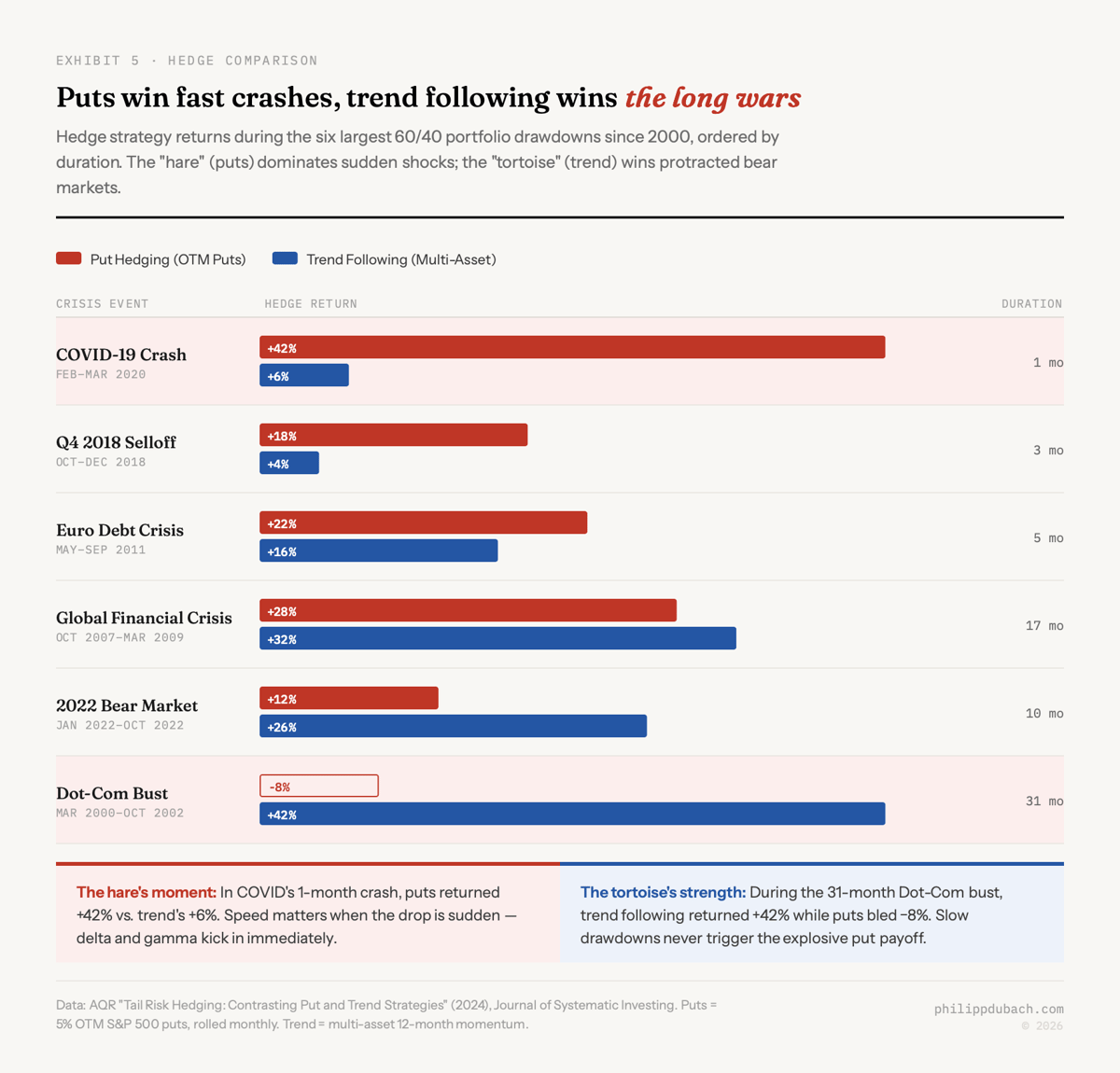

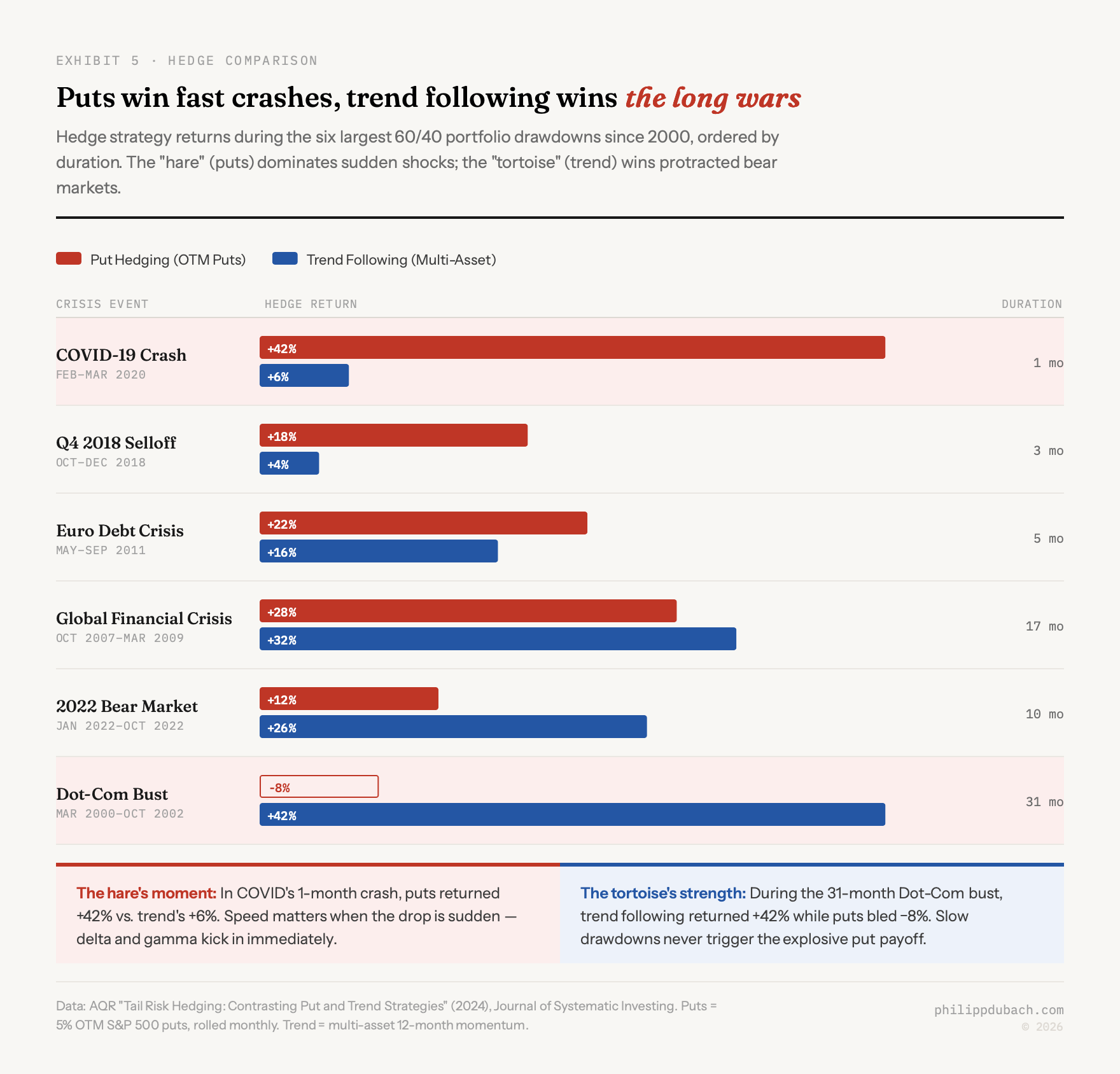

AQR’s research on tail hedging, published in the Journal of Systematic Investing, complicates the picture in a way I find genuinely useful for portfolio construction. They compare two fundamental approaches: buying out-of-the-money puts and multi-asset trend-following.

Puts act as the hare. They deliver spectacular returns in sudden crashes like COVID, when put-buying strategies returned over +42% in a single month. But they are expensive to maintain and their long-term expected return is negative. Trend-following acts as the tortoise. It cannot provide the same reliable downside protection as index puts, but has delivered surprisingly consistent safe-haven performance when most needed while earning positive long-run returns.

AQR’s follow-up paper examined the five largest 60/40 drawdowns since 2000 and found that options-based strategies outperformed in shorter drawdowns while trend-following posted its most impressive returns during protracted bear markets. Since longer drawdowns are arguably more damaging to long-term wealth (they impair compounding for extended periods, which brings us back to the variance tax), AQR leans toward trend-following as the more practical hedge for most investors.

But the strategies are genuinely complementary. Recent academic work combining both approaches via a portable alpha framework found statistically significant alpha of 0.25% per month after controlling for traditional equity factors, with the strongest outperformance during periods of market turmoil. Puts for the fast crash, trend for the slow bleed.

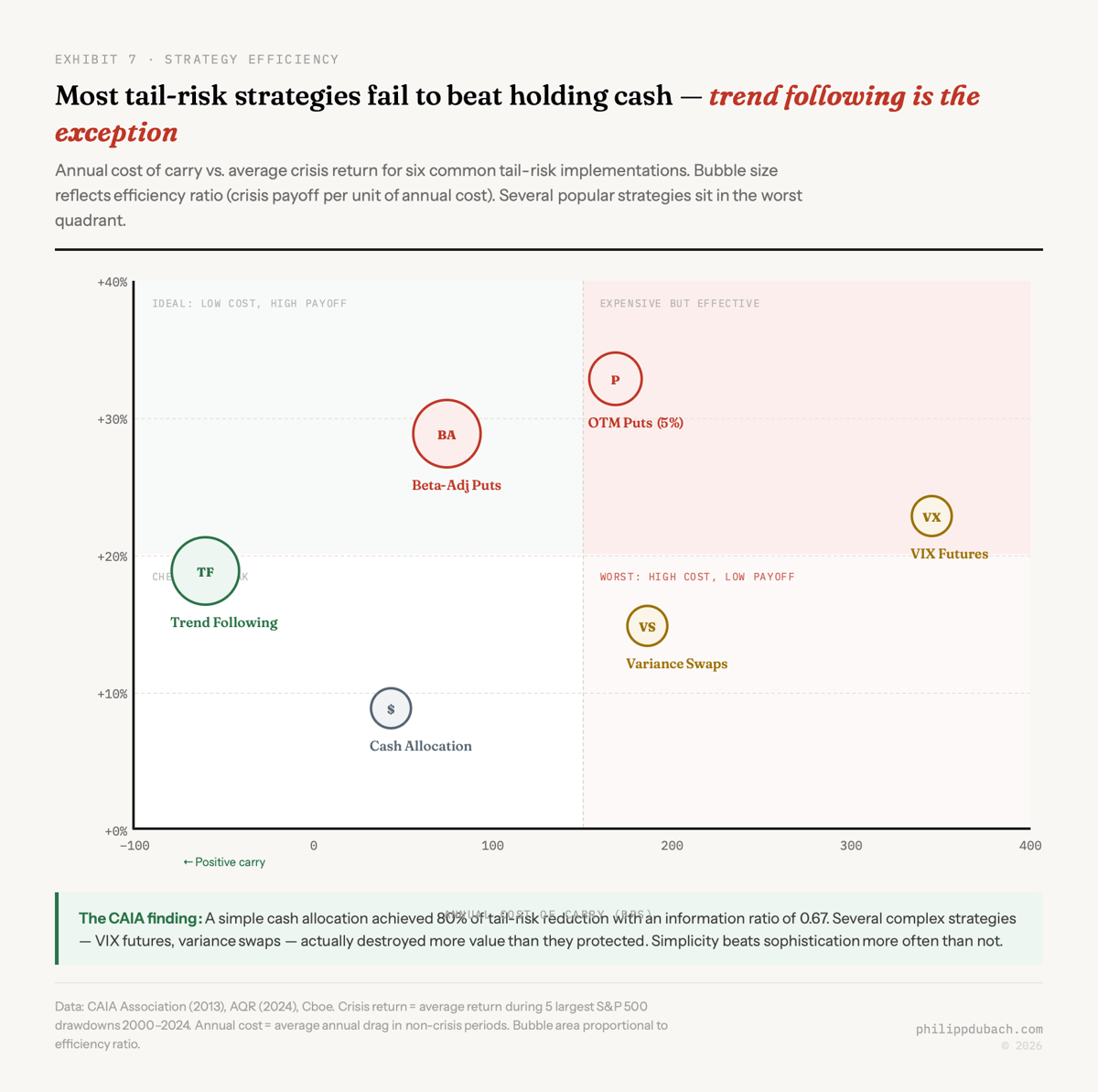

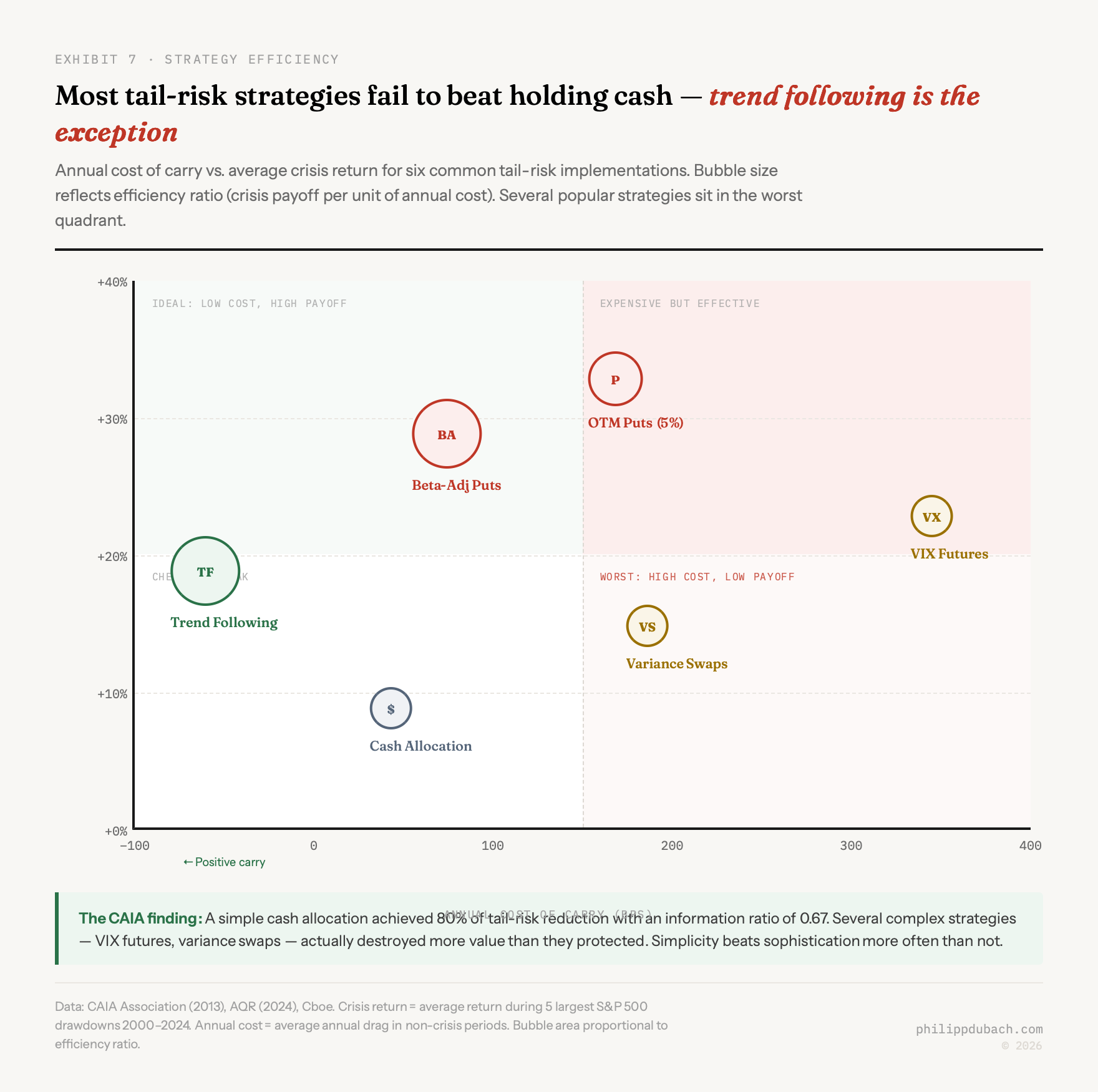

Where most tail hedges fail, and the benchmark problem

Here is where most investors get burned. A CAIA Association paper compared multiple tail-risk strategies against a deliberately boring benchmark: holding cash. Cash achieved a reduction of 80% of portfolio tail risk and 81% of portfolio standard deviation compared to an S&P 500-only portfolio, with an information ratio of 0.67. Several popular tail-risk strategies, particularly those involving short-dated VIX futures and 1-month variance swaps, actually failed to beat this cash benchmark, with performance drags of 355 and 203 basis points respectively.

This is the finding that should make any allocator uncomfortable. If your sophisticated tail hedge cannot beat holding Treasury bills, you are paying for complexity that destroys value. The specific implementation matters enormously, and many “obvious” approaches (VIX futures being the most popular) are structurally flawed because of contango decay in the VIX term structure that steadily erodes returns during calm periods.

A 2025 paper in the Journal of Futures Markets adds a related finding: naïve hedging strategies outperformed more complex models for tail-risk hedging, consistent with earlier findings on variance-minimizing hedges. The explanation lies in model risk. Sophisticated approaches require more assumptions about market dynamics, and when those assumptions are wrong (as they inevitably are during the very tail events you are trying to hedge) the resulting model misspecification can leave hedging portfolios with higher-than-expected risk. This is a familiar problem in ML: the more parameters you fit on in-sample data, the worse your out-of-sample performance when the regime changes. Tail events are precisely when regimes change.

There is also a benchmark problem that poisons the conversation around tail hedging. A portfolio of stocks plus put options gets compared against a portfolio of just stocks. When the market rises steadily for years, the hedged portfolio naturally underperforms and the hedge looks like a waste of money. This comparison is intellectually dishonest. A portfolio with puts has less risk than a portfolio without them. Comparing them as equivalent is like comparing a levered equity portfolio to an unlevered one and concluding that leverage “works” because it outperformed during a bull market. The appropriate comparison for a hedged portfolio is against a portfolio with similar risk, whether achieved through lower equity allocation, higher cash balances, or other risk-reducing measures. When Bhansali and Davis (2010) conducted this more appropriate comparison, they found that offensive tail hedging, using the freed-up risk budget to increase equity exposure, resulted in superior risk-adjusted performance. The hedge was not a drag. It was an enabler.

What I take away

Most of the interesting questions in finance are not about individual positions but about what positions enable. Tail hedging is boring in isolation. What it does to the rest of the portfolio, the willingness to stay invested during drawdowns, the capacity to hold concentrated positions, the ability to rebalance into cheap assets after crashes rather than capitulating, that is where the return comes from. Spitznagel and Goldman agree on this even if they agree on little else.

The optimal tail hedge allocation is a psychological question, not a mathematical one. Most practitioners suggest 1 to 5% of portfolio value, sized to offset a meaningful portion of equity losses during a severe 30 to 50% drawdown. But the right number is the one that allows you to stay invested in your core portfolio through the worst of times without abandoning the strategy. If you cannot stomach three years of negative carry on a put overlay, the correct allocation for you is zero, not five percent.

The framing I find most useful is Goldman’s. Do not evaluate the hedge in isolation. Evaluate what it enables. A 3% tail hedge allocation that reduces max drawdown from 50% to 25% frees up enough risk budget to increase equity exposure by 10 to 15 percentage points. The incremental return from that higher equity allocation over a full market cycle will, in most scenarios, more than compensate for the cost of the hedge. The hedge is the enabler, not the alpha.

Whether you implement this with puts, trend-following, or both depends on your time horizon and what kind of drawdown keeps you up at night. Fast crashes favor puts. Slow bleeds favor trend. If you do not know which one is coming (you do not), blend them.

The caveats are real. All backtests benefit from hindsight. Transaction costs and bid-ask spreads in options markets are material and not fully captured in the CBOE indices used as benchmarks. The behavioral challenge of holding a position that bleeds money most of the time should not be underestimated, especially for allocators who report to investment committees that look at monthly returns.

But the turkey metaphor from One River’s presentation is apt. A statistician turkey who, right up until Thanksgiving, can prove with perfect p-values that the farmer is benevolent. The turkey’s model is flawless within the distribution of observed data. The problem is that the data does not contain the event that matters most. Tail hedging is the strategy of the paranoid turkey. The empirical evidence suggests this paranoia can be not just protective but profitable, provided you implement it with discipline and use it not as a way to avoid risk but as a foundation for taking more of it.