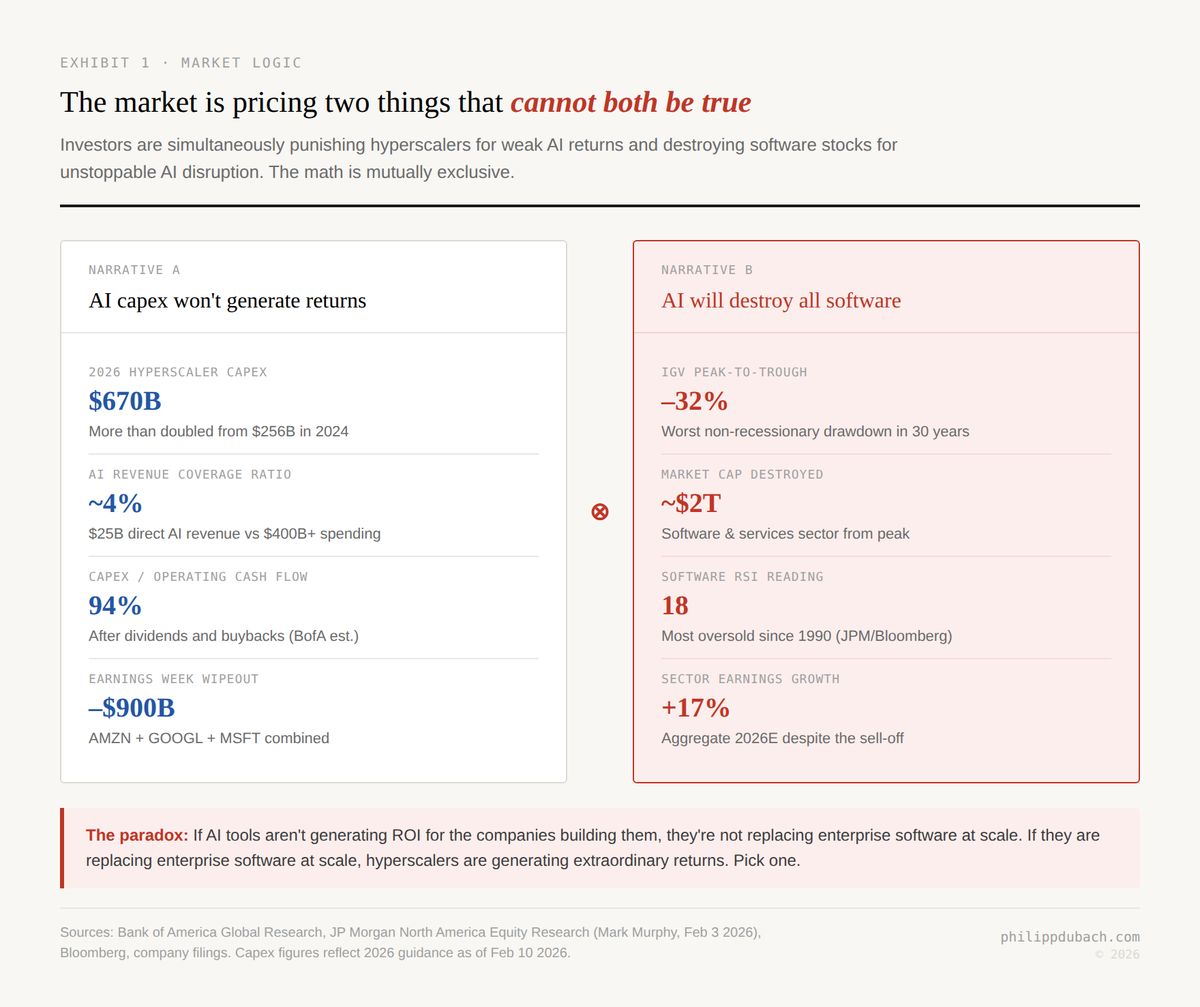

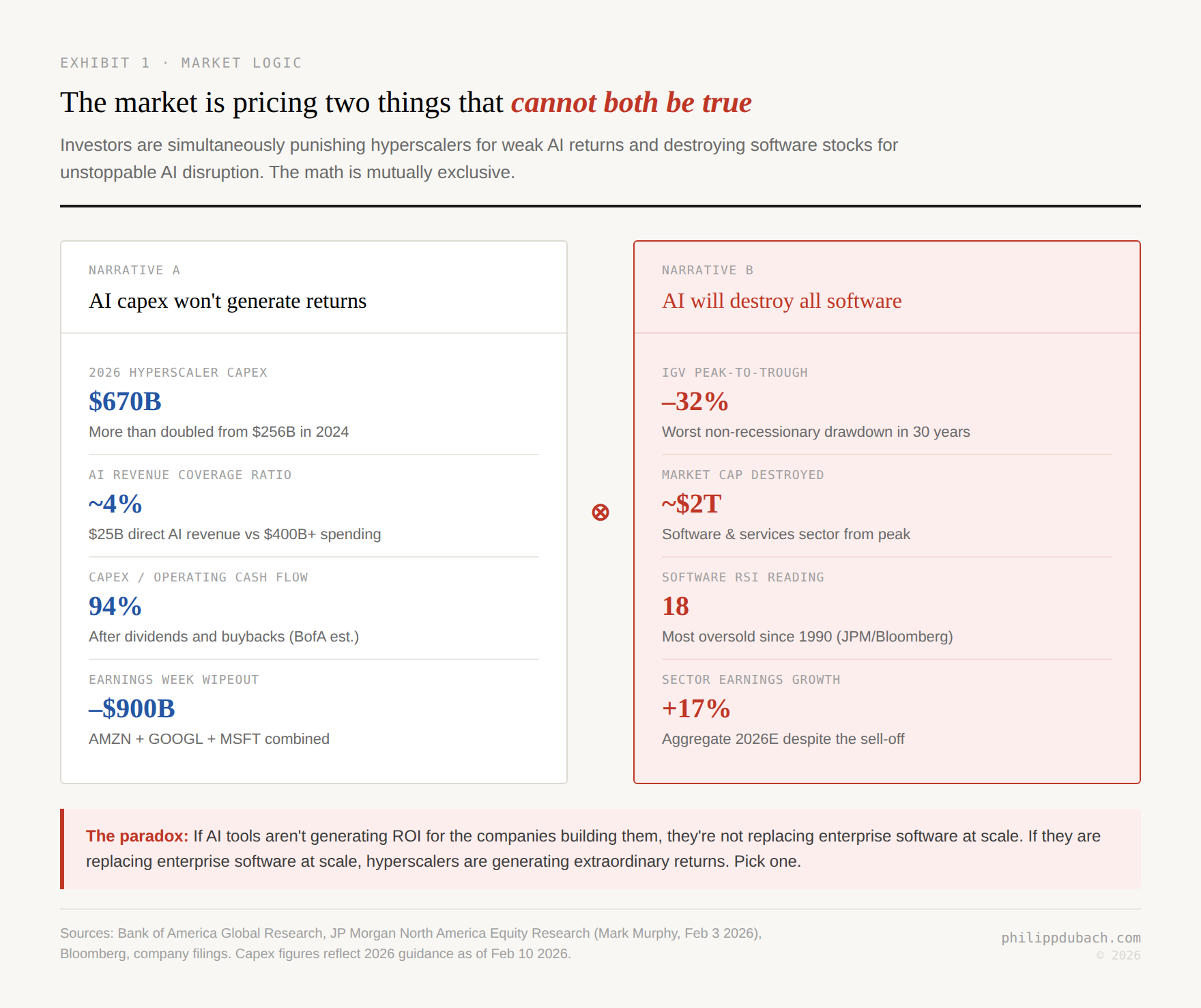

The market is simultaneously pricing AI capex failure and AI destroying all software. Both cannot be true.

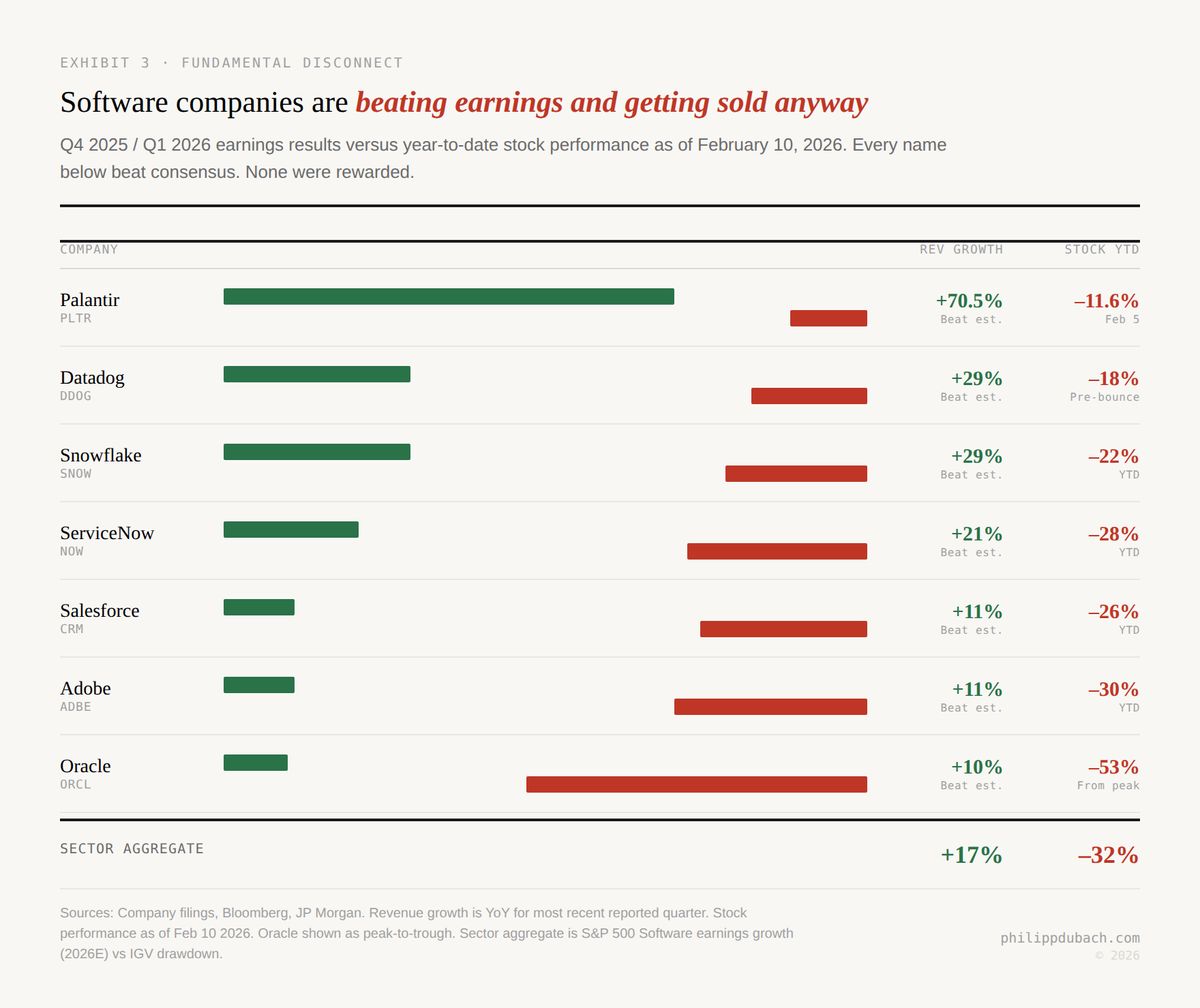

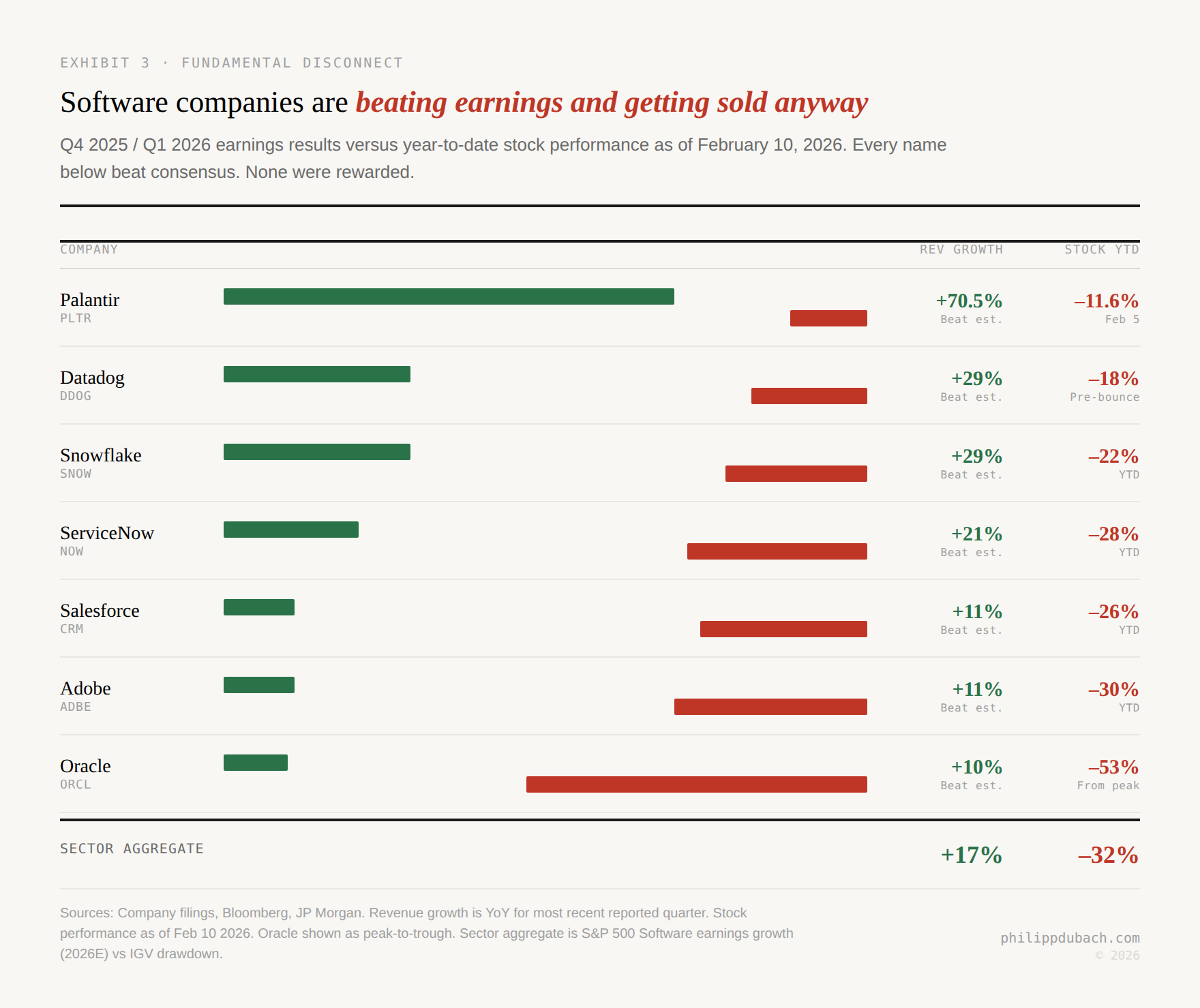

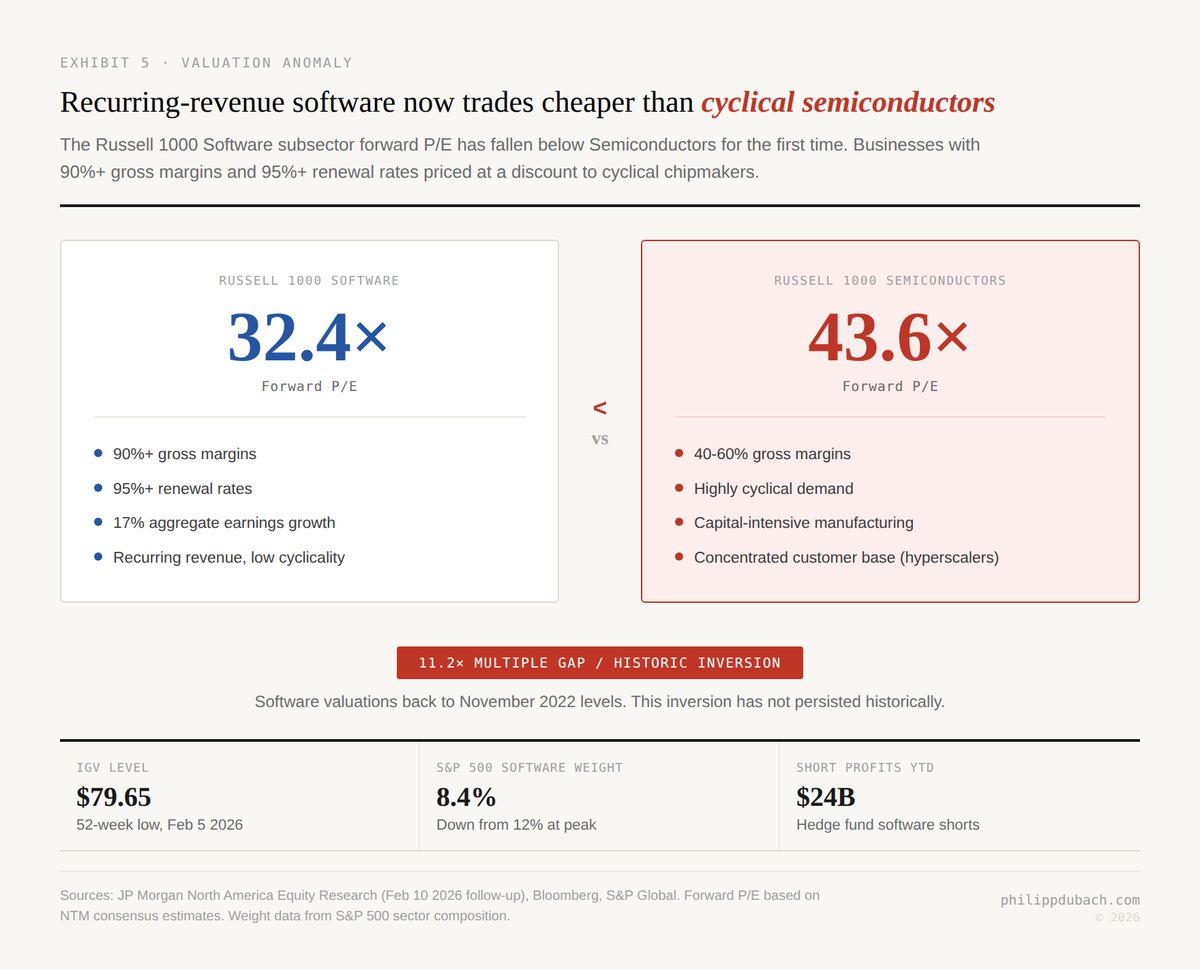

Anthropic released 11 open-source plugins for Claude Cowork on January 30. Apache-2.0 licensed, file-based, running in a macOS-only research preview. Within a week, the IGV software ETF had fallen 32% from its September peak to a 52-week low of $79.65, roughly $2 trillion in market cap had evaporated, and hedge funds had made $24 billion shorting the sector. The RSI hit 18, the most oversold reading since 1990. JP Morgan titled their note “Software Collapse Broadens with Nowhere to Hide.” Jefferies coined the term SaaSpocalypse.

Bank of America’s Vivek Arya identified the paradox at the center of this: investors are simultaneously punishing hyperscaler stocks because AI capex might generate weak returns, while destroying software stocks because AI adoption will be so pervasive it renders all existing software obsolete. Both cannot hold simultaneously. If AI tools aren’t generating meaningful ROI, they’re not replacing enterprise software at scale. If they are replacing enterprise software at scale, the hyperscalers are earning extraordinary returns on their infrastructure investment.

This paradox can only resolve in one of three ways: AI adoption is real and hyperscaler capex is justified, AI adoption stalls and software incumbents are fine, or the truth is somewhere in between and the market has mispriced both sides. The first two are internally consistent. The market is pricing neither.

The bear case

The structural argument against enterprise software is serious and worth stating on its own terms.

Enterprise software monetizes through per-seat licensing. The business model depends on a stable correlation between headcount and license count. AI agents break that correlation. If 10 agents do the work of 100 people, the software doesn’t get replaced directly, the headcount that justifies the seats does, and CRM seat revenue drops with it. AlixPartners estimates up to $500 billion in enterprise software revenue could be at risk over time. IDC predicts pure seat-based pricing will be obsolete by 2028.

The moat question is equally uncomfortable. Enterprise software’s traditional defense was the trained-user-interface moat: the years of institutional muscle memory that makes switching costs prohibitive. Databricks CEO Ali Ghodsi told TechCrunch that this moat collapses when the interface becomes natural language. If the value of Salesforce or ServiceNow lived in their UI rather than their data, and the UI can now be replicated by a general-purpose model, then the moat was shallower than anyone thought. VC has fled traditional SaaS entirely; as one investor noted, “an entrepreneur approaching a VC fund today with a SaaS startup won’t even reach the pitch stage.”

The build-versus-buy equation is inverting in real time. Klarna ditched Salesforce and Workday, consolidated onto its own AI-augmented stack, and used an OpenAI-powered bot to handle work that previously required 700 employees. SaaStr’s analysis of Gartner’s $1.43 trillion 2026 software spending forecast reveals that roughly 9 percentage points of the 14.7% headline growth is price increases on existing software, not net new demand. AI is eating SaaS budgets, redirecting IT spend toward infrastructure while reducing the headcount that generates software seats.

This is the case priced into the IGV at $80.

The bull case

The structural argument for enterprise software rests on a distinction the current sell-off is ignoring entirely.

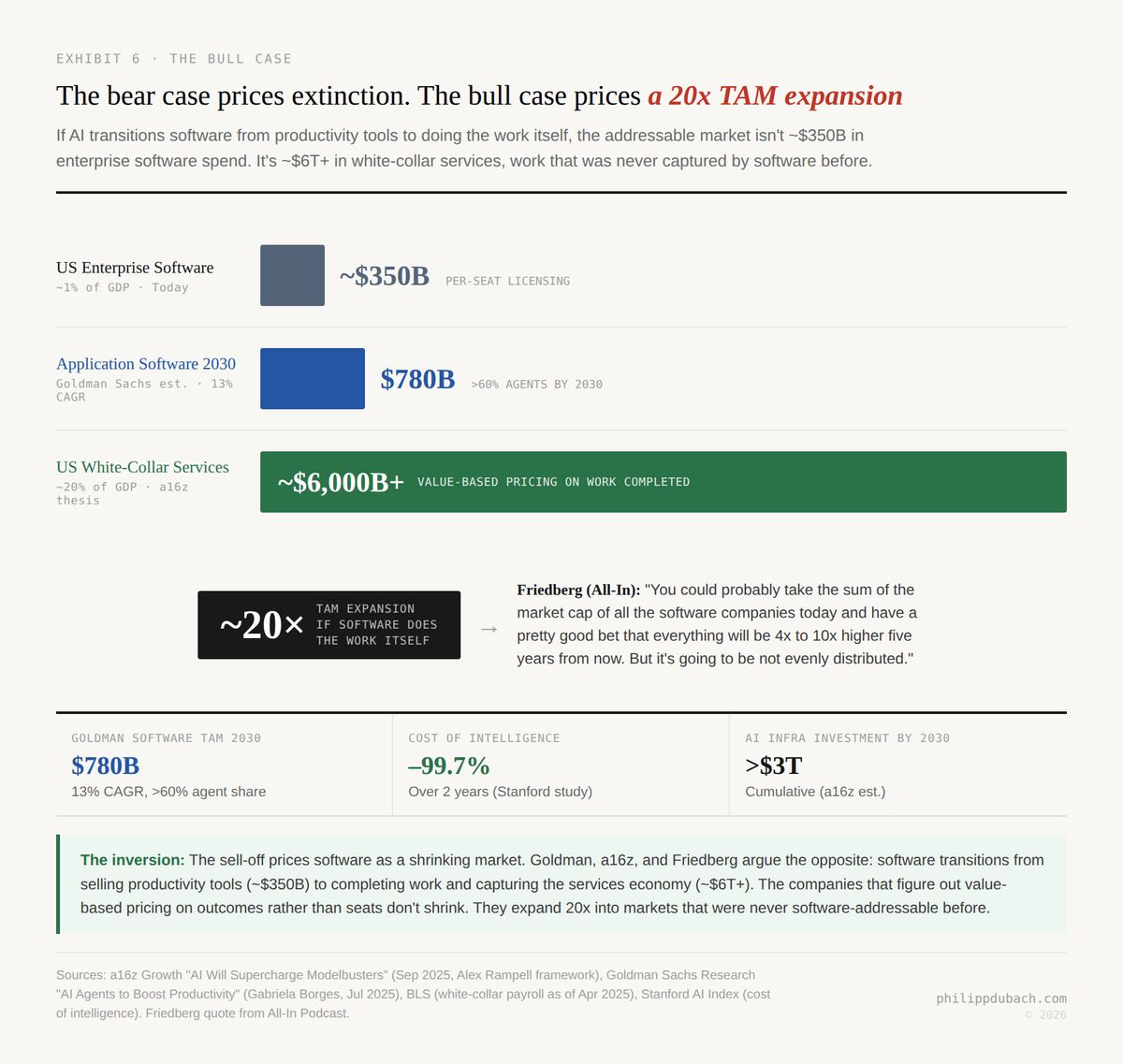

The bear case assumes a shrinking TAM. Goldman Sachs Research argues the opposite: the application software market grows to $780 billion by 2030 at a 13% CAGR, with agents accounting for over 60% of the total. The profit pool shifts from SaaS seats to agentic workloads, but the overall market gets larger, not smaller. a16z’s Alex Rampell takes it further: if AI enables software to not just enhance productivity but actually complete work, the addressable market isn’t roughly $350 billion in enterprise software spend (about 1% of GDP). It’s the ~$6 trillion white-collar services market (~20% of GDP), a 20x expansion into work that was never software-addressable before.

David Friedberg made the most provocative version of this argument on the All-In Podcast: software transitions from helping people do work, to completing work, to doing work humans cannot do. At that point, pricing shifts from per-seat to value-based, and “SaaS basically takes over the services economy.” His estimate: the combined market cap of software companies could be 4x to 10x higher in five years, but “not evenly distributed.”

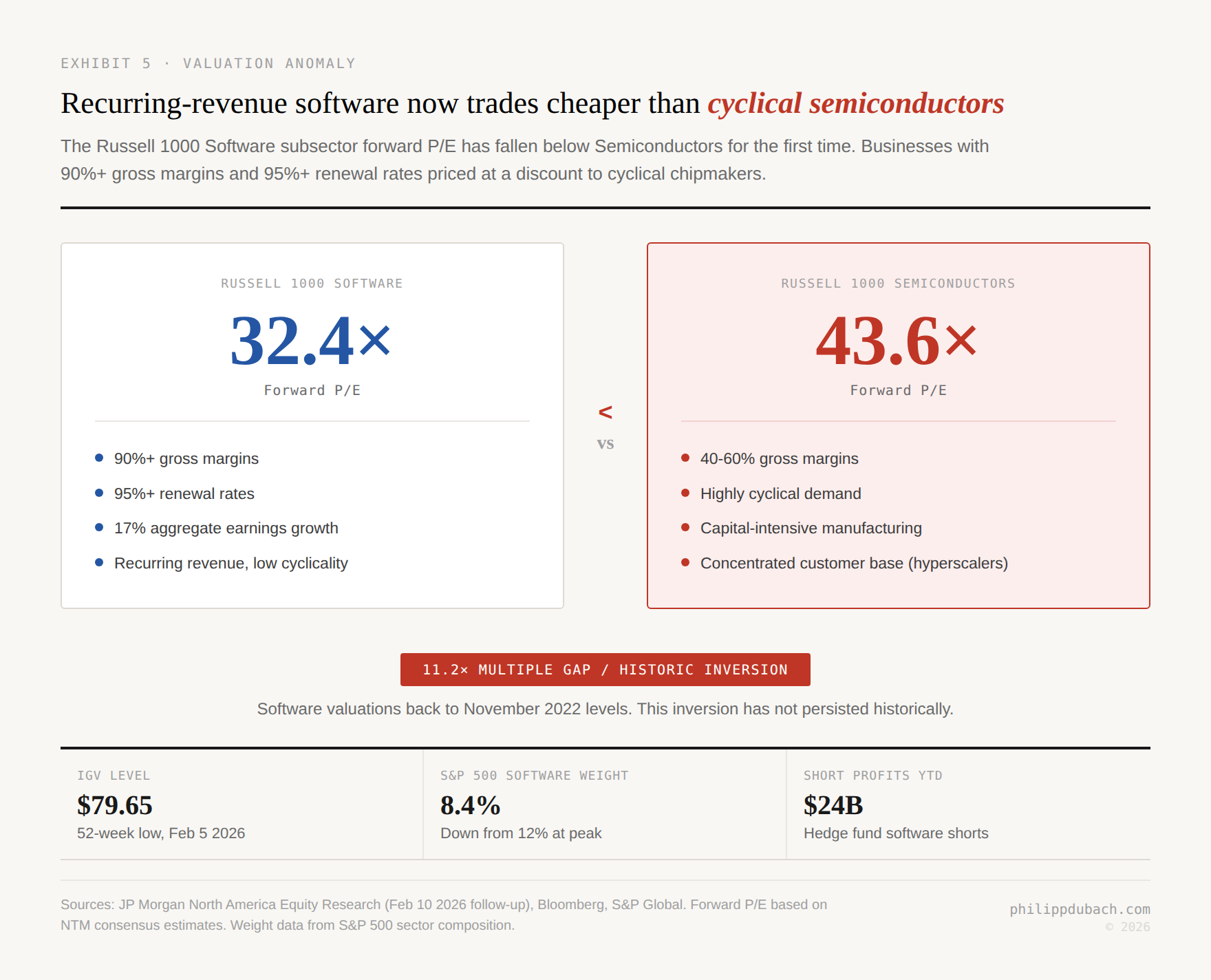

The valuation picture strengthens this framing. The sector is delivering 17% aggregate earnings growth in 2026 while trading at November 2022 EV/Sales multiples, back when the Fed was aggressively hiking into recession fears. The Russell 1000 Software subsector now trades at 32.4x forward earnings versus 43.6x for semiconductors. Recurring-revenue businesses with 90%+ gross margins and 95%+ renewal rates trade at a lower multiple than cyclical chipmakers with 40–60% margins and concentrated customer bases. Historically that’s an inversion that has not persisted.

This is the case that BofA called a paradox and JP Morgan called a mispricing.

The capex question that connects both sides

There is a number that both cases have to account for, and it’s the one that determines which side of the paradox resolves first.

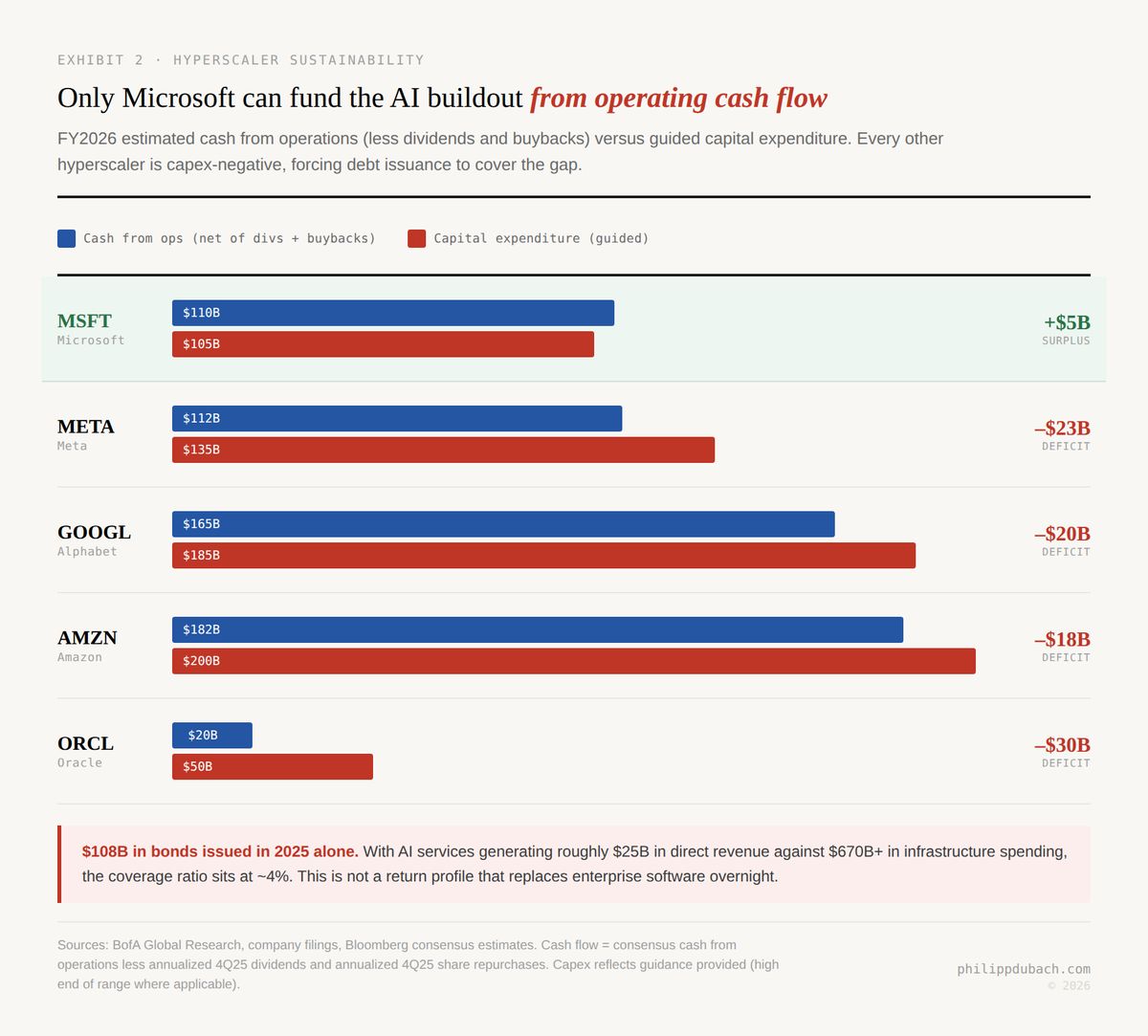

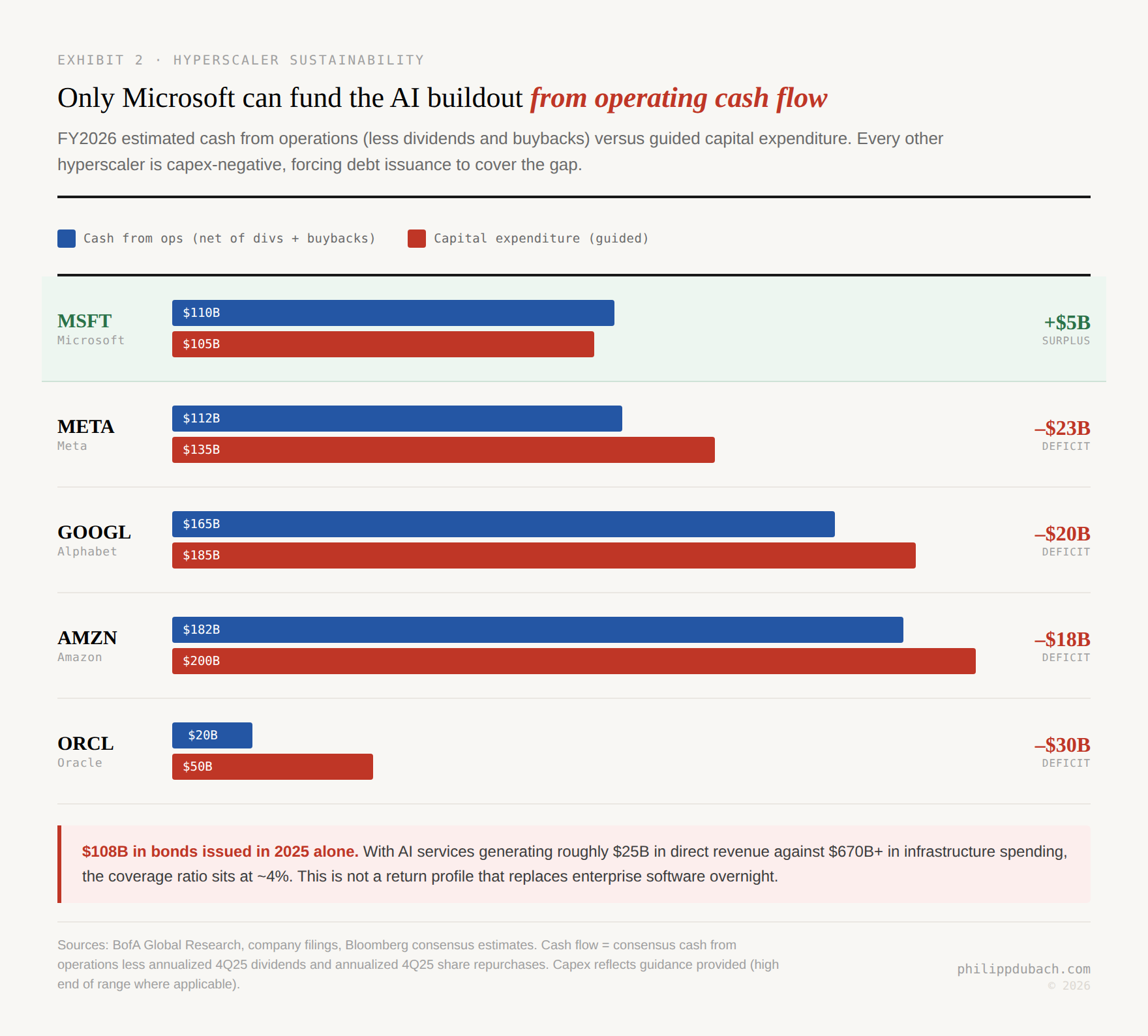

Combined 2026 capex guidance from Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and Oracle now approaches $700 billion, more than doubling from $256 billion in 2024. Bank of America calculates this consumes 94% of operating cash flows after capital returns. The Big Five raised $108 billion in bonds in 2025. AI-related services generate roughly $25 billion in direct revenue against $400+ billion in annual infrastructure spending, a coverage ratio of about 4%.

If the bear case is right and AI agents are replacing enterprise software at scale, this capex should already be generating enormous returns. It isn’t. If the bull case is right and AI is expanding the TAM into the services economy, this capex is early-stage infrastructure investment that will compound over a decade. In that reading, $700 billion in annual spend is the foundation of a $6 trillion market, not a write-off. Both interpretations require the same capex figure to mean something fundamentally different. The market hasn’t decided which.

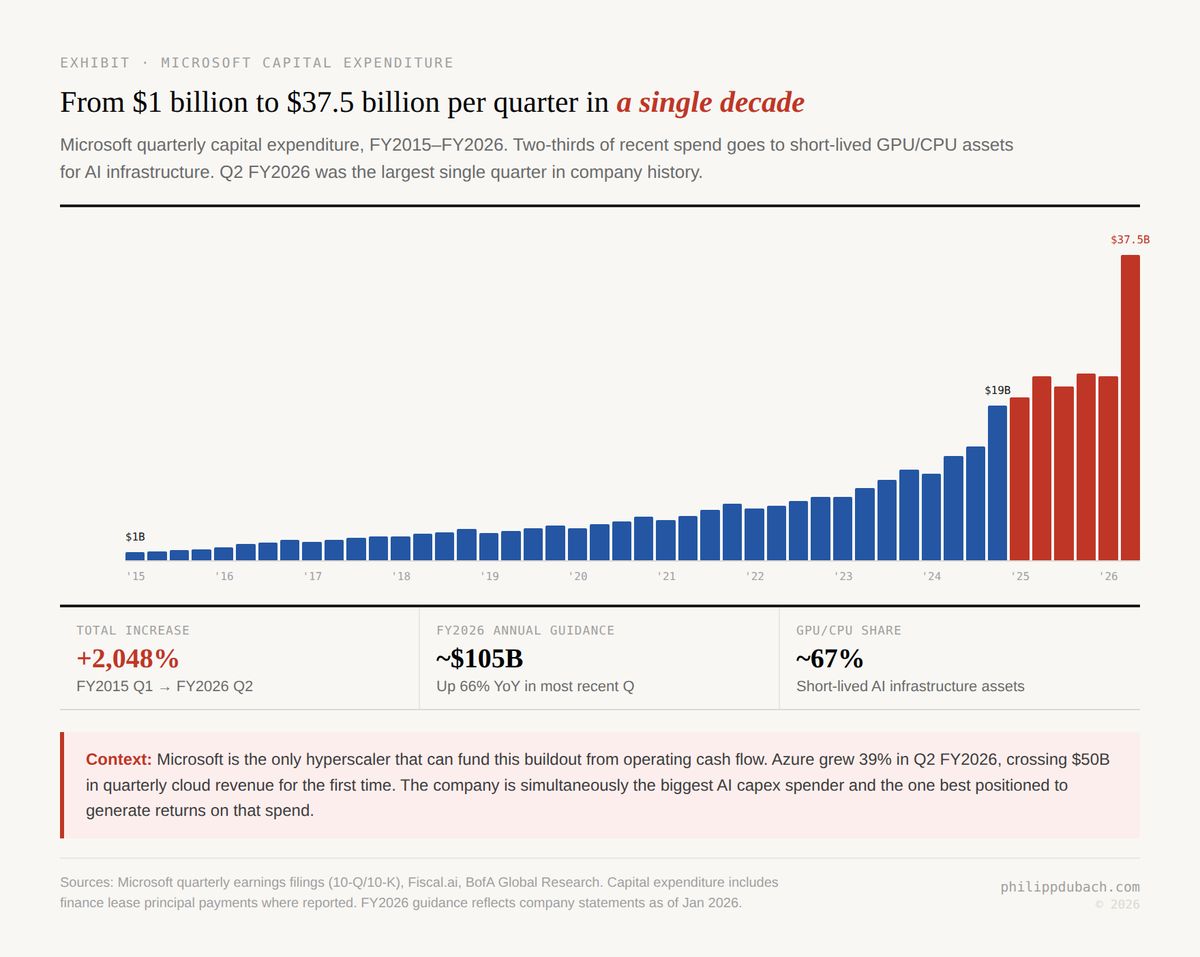

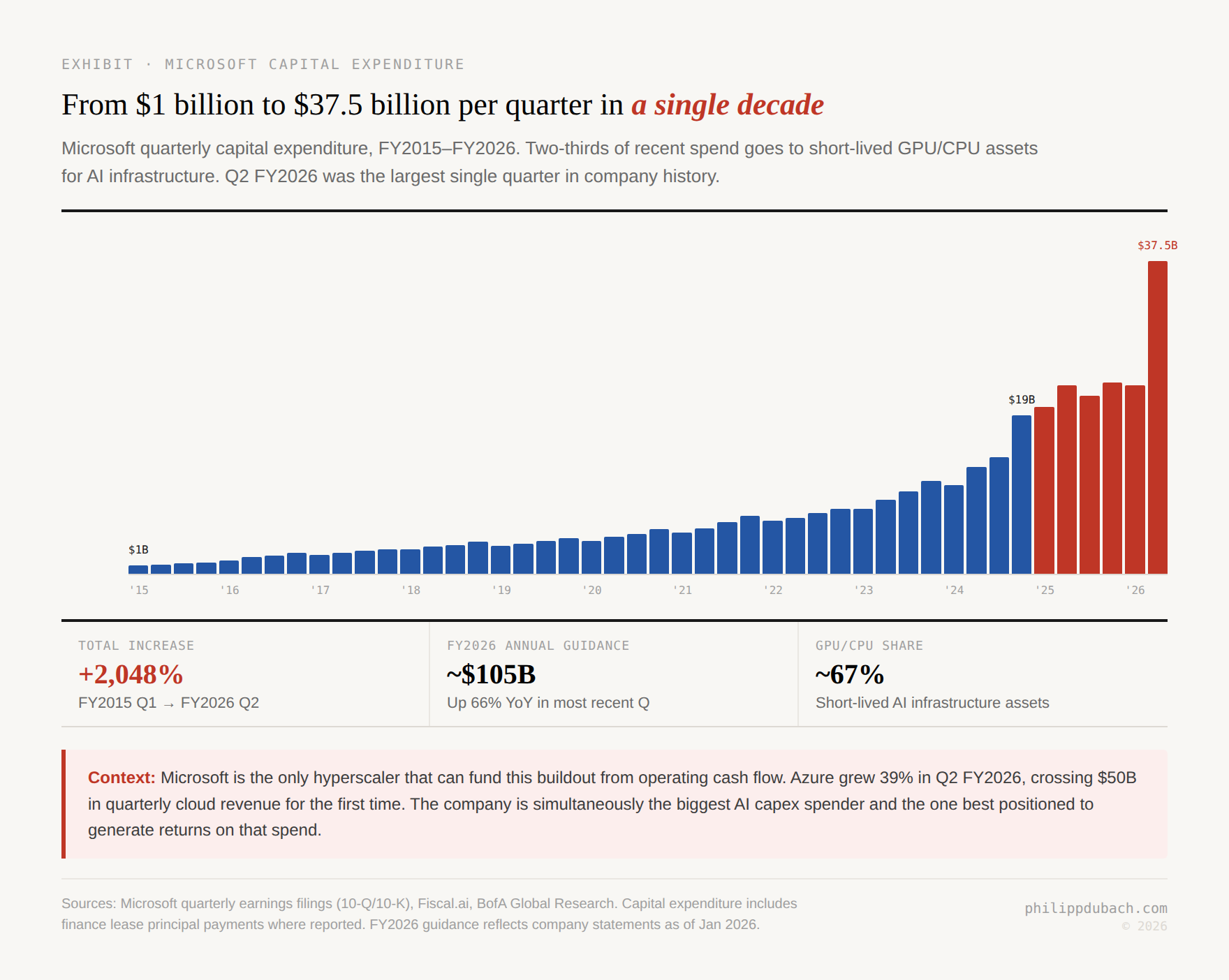

Microsoft is the sharpest illustration of this tension. Quarterly capex went from $1 billion in early 2015 to a record $37.5 billion in Q2 FY2026, with roughly two-thirds going to short-lived GPU/CPU assets. And yet Microsoft is the only hyperscaler that can fund this buildout from operating cash flow. Azure grew 39% in Q2 FY2026, crossing $50 billion in quarterly cloud revenue for the first time. The company is simultaneously the biggest AI capex spender, the one best positioned to generate returns on that spend, and the company whose products (365, Dynamics, Azure) are supposedly being disrupted by Claude plugins. The market is punishing all three at once.

Bifurcation, not extinction

A 60% recession probability, a partial government shutdown, elevated tariffs, and a structural pricing transition are being sold as a single story. They aren’t. Separating the macro from the structural requires asking which software categories are genuinely at risk and which are being sold by association.

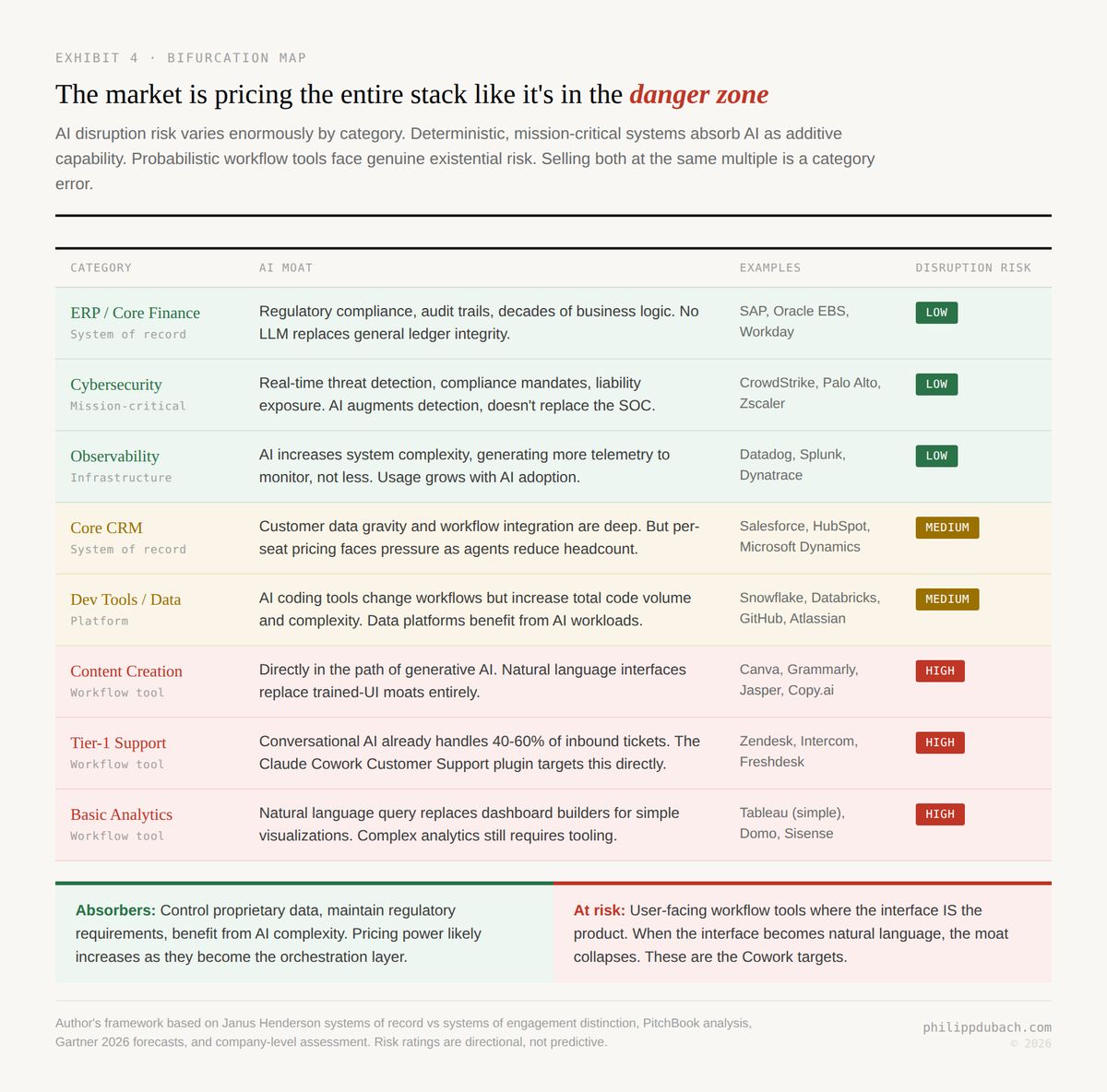

Janus Henderson makes a useful distinction between “systems of record” and “systems of engagement.” Systems of record are deeply embedded in business processes, require regulatory compliance, and carry enormous switching costs: ERP, core finance, cybersecurity, observability. PitchBook described replacing one as “effectively open-heart surgery for an enterprise.” Systems of engagement are user-facing workflow tools where the interface is the product: content creation, tier-1 support, basic analytics. When the interface becomes natural language, that moat collapses.

The bear case is correct about the second category. The bull case is correct about the first. The market is wrong to price them identically. Selling both at the same multiple compression implies that switching costs, regulatory requirements, data gravity, and enterprise procurement cycles have all vanished simultaneously. Gartner predicts over 40% of agentic AI projects will be cancelled by 2027. Salesforce’s Agentforce reached 18,500 customers in its first year, the fastest-adopted organic product in company history. These are not the behaviors of a category that has been disrupted. They are the behaviors of incumbents absorbing a new paradigm.

Stated precisely: the bear case is a zero-sum repricing where AI agents compress existing software revenue by eliminating seats and commoditizing interfaces. The bull case is a positive-sum expansion where the surviving software companies capture the $6 trillion in white-collar services that was never software-addressable before. The cost of intelligence has fallen 99.7% in two years (Stanford AI Index). Cumulative AI infrastructure investment is expected to exceed $3 trillion by 2030. That kind of capital deployment doesn’t produce a world where software shrinks. It produces a world where the definition of “software” expands to include most of the services economy.

I wrote recently about how passive flows create mechanical, price-insensitive selling that overwhelms fundamental buyers. This sell-off is a textbook case. JP Morgan’s Murphy described index arbitrage basket selling, programmatic de-grossing, and passive flow liquidity vacuums. The IGV recorded its highest single-day trading volume in 25 years. JP Morgan’s follow-up argued the sell-off has gone far enough. BofA called it a paradox that “doesn’t make any sense.” History suggests these kinds of extremes, the 2016 LinkedIn panic, the 2022 rate-shock drawdown, the January 2025 DeepSeek crash, tend to mark inflection points rather than starting points for further decline.

The hardest trade right now is the one that requires distinguishing between stocks that are cheap because they’re broken and stocks that are cheap because the market is broken. The IGV at $80, with a 30-year-extreme RSI, pricing in an extinction event that operating results don’t remotely support, looks a lot more like the latter.