Let’s say your portfolio returned +60% in 2024, then fell 40% in 2025. That’s an annualized average return of +10%. Actual return after two years: minus 4% (i.e $100 * 1.6 * 0.6 = $96).

That 14-point gap is what we call the variance tax aka variance drain or volatility drag and it’s probably one of the most underappreciated forces in investing.

Take any series of returns with arithmetic mean μ and volatility σ. The compound growth rate, the one that actually determines your wealth, is approximately:

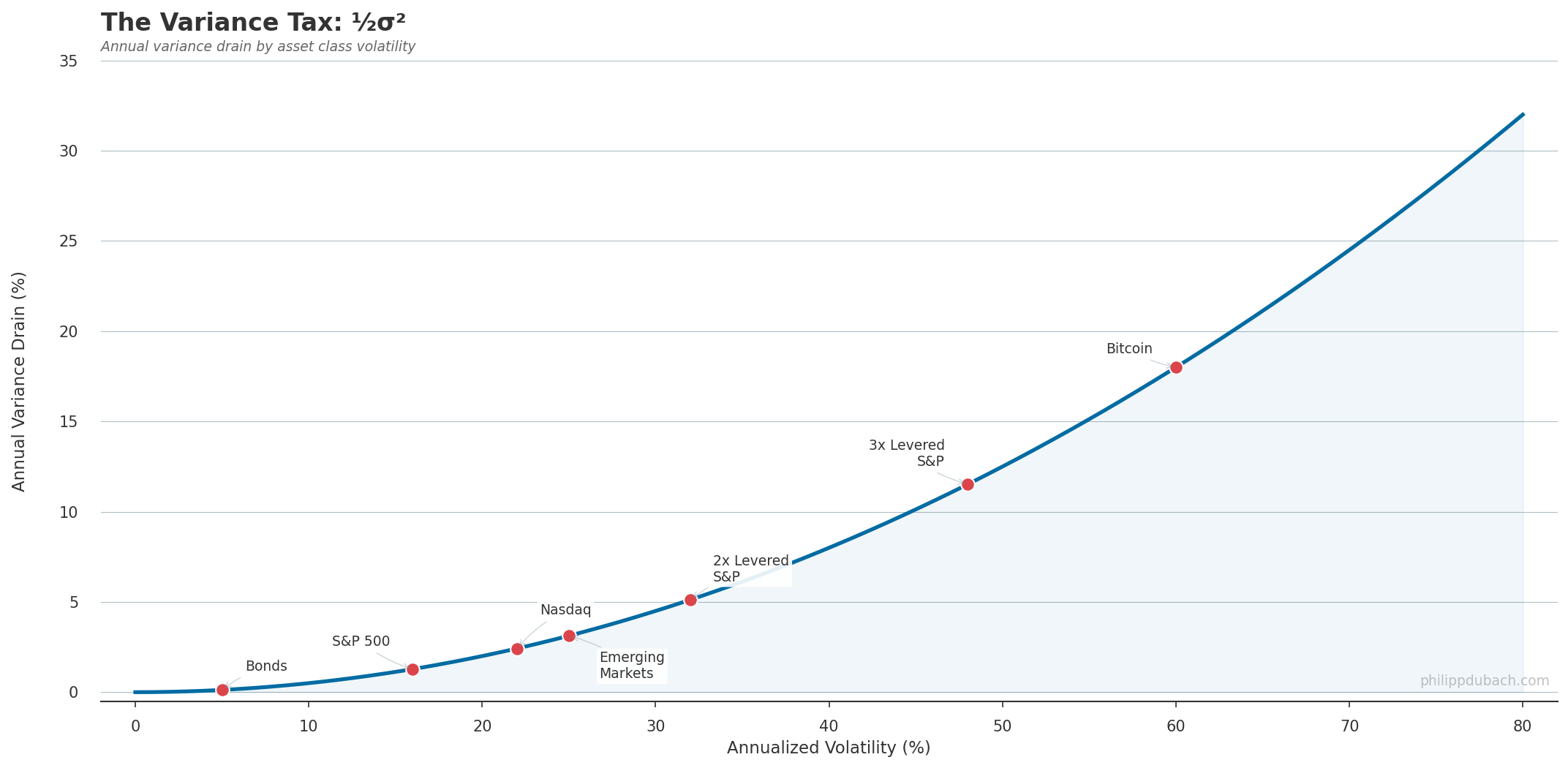

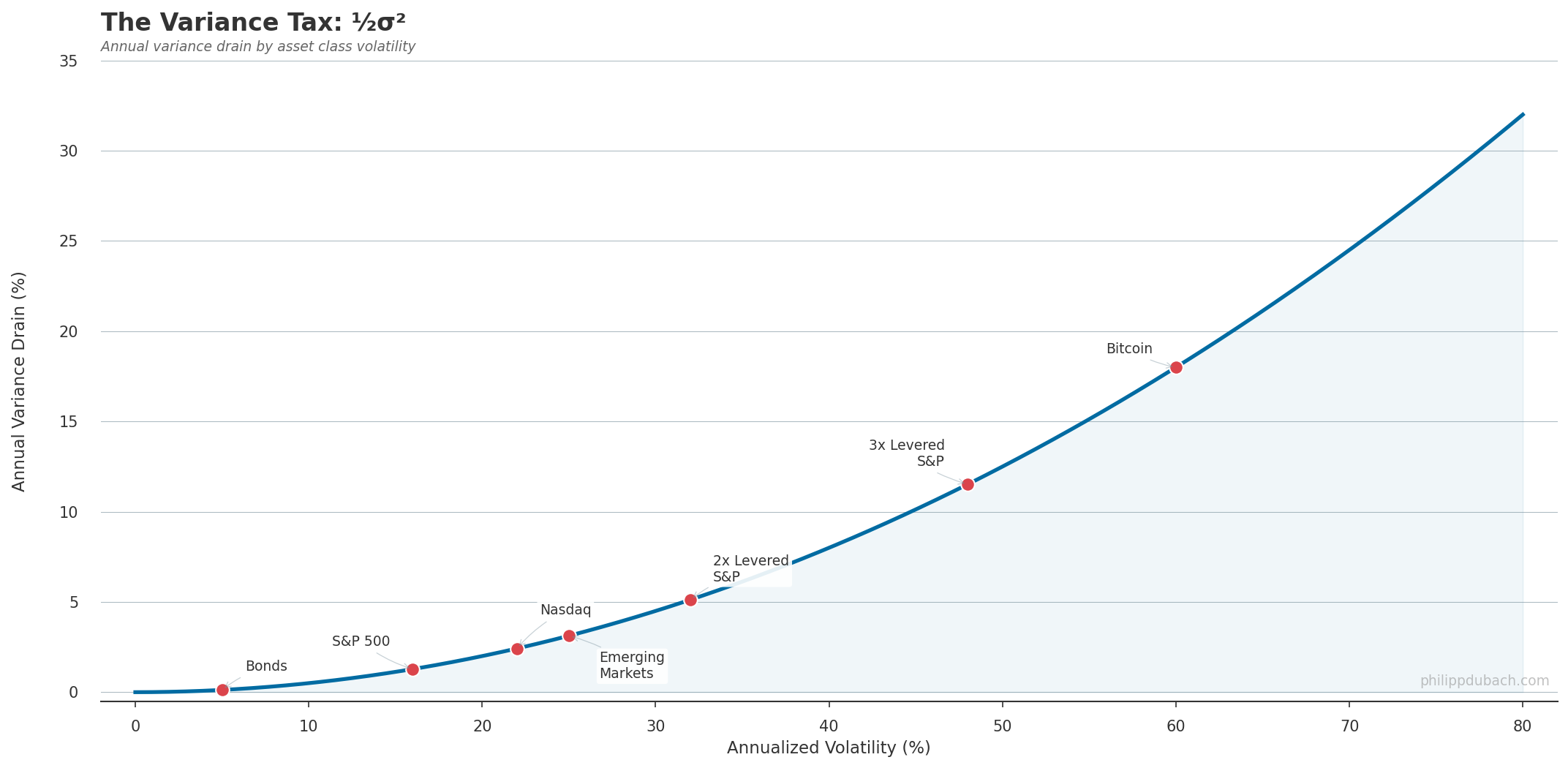

$$G ≈ μ − ½σ²$$This comes from a second-order Taylor expansion of ln(1+r). Take expectations, and the mean log return equals the arithmetic mean minus half the variance. Everything else drops out. Half the variance. That is the tax. The same correction term appears when you solve geometric Brownian motion via Itô’s lemma (the drift of log(S) is μ − σ²/2, not μ) so whether you come at it from discrete compounding or continuous-time stochastic calculus, you land in the same place. And because it is quadratic, doubling volatility does not double the cost. It quadruples it. And what we learned during covid, if anything at all, is that we generally have a hard time to mentally abstract exponential growth rates.

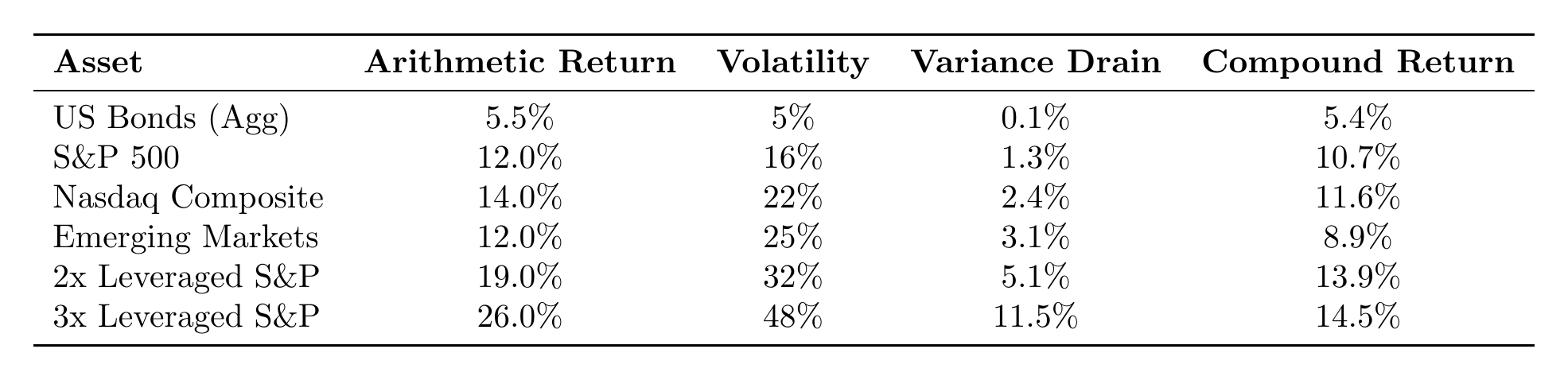

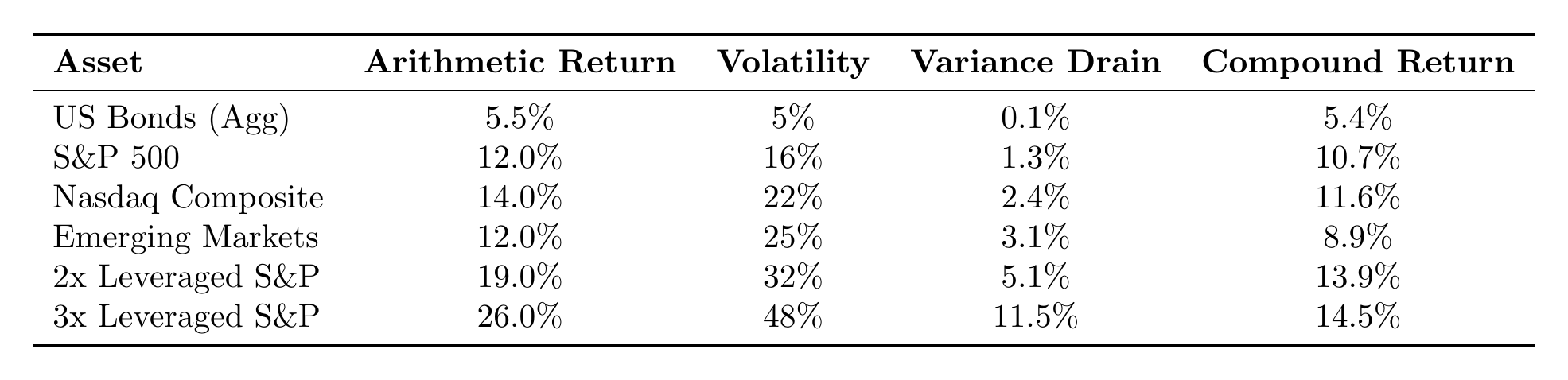

Treasury bonds at 5% vol pay about 0.1% per year in variance drain. Barely noticeable. The S&P 500 at 16% vol pays 1.3%. A 3x leveraged ETF at 48% vol pays 11.5%. Jacquier, Kane, and Marcus (2003) studied S&P 500 returns from 1926 to 2001: arithmetic mean 12.49%, geometric mean 10.51%. The gap is 1.98 percentage points. The formula predicts ½ × 0.203² = 2.06%.

Treasury bonds at 5% vol pay about 0.1% per year in variance drain. Barely noticeable. The S&P 500 at 16% vol pays 1.3%. A 3x leveraged ETF at 48% vol pays 11.5%. Jacquier, Kane, and Marcus (2003) studied S&P 500 returns from 1926 to 2001: arithmetic mean 12.49%, geometric mean 10.51%. The gap is 1.98 percentage points. The formula predicts ½ × 0.203² = 2.06%.

Looking at the last row, we see that tripling leverage triples the arithmetic return but delivers nearly the same compound return as 2x. The linear gain gets eaten by the quadratic penalty.

Looking at the last row, we see that tripling leverage triples the arithmetic return but delivers nearly the same compound return as 2x. The linear gain gets eaten by the quadratic penalty.

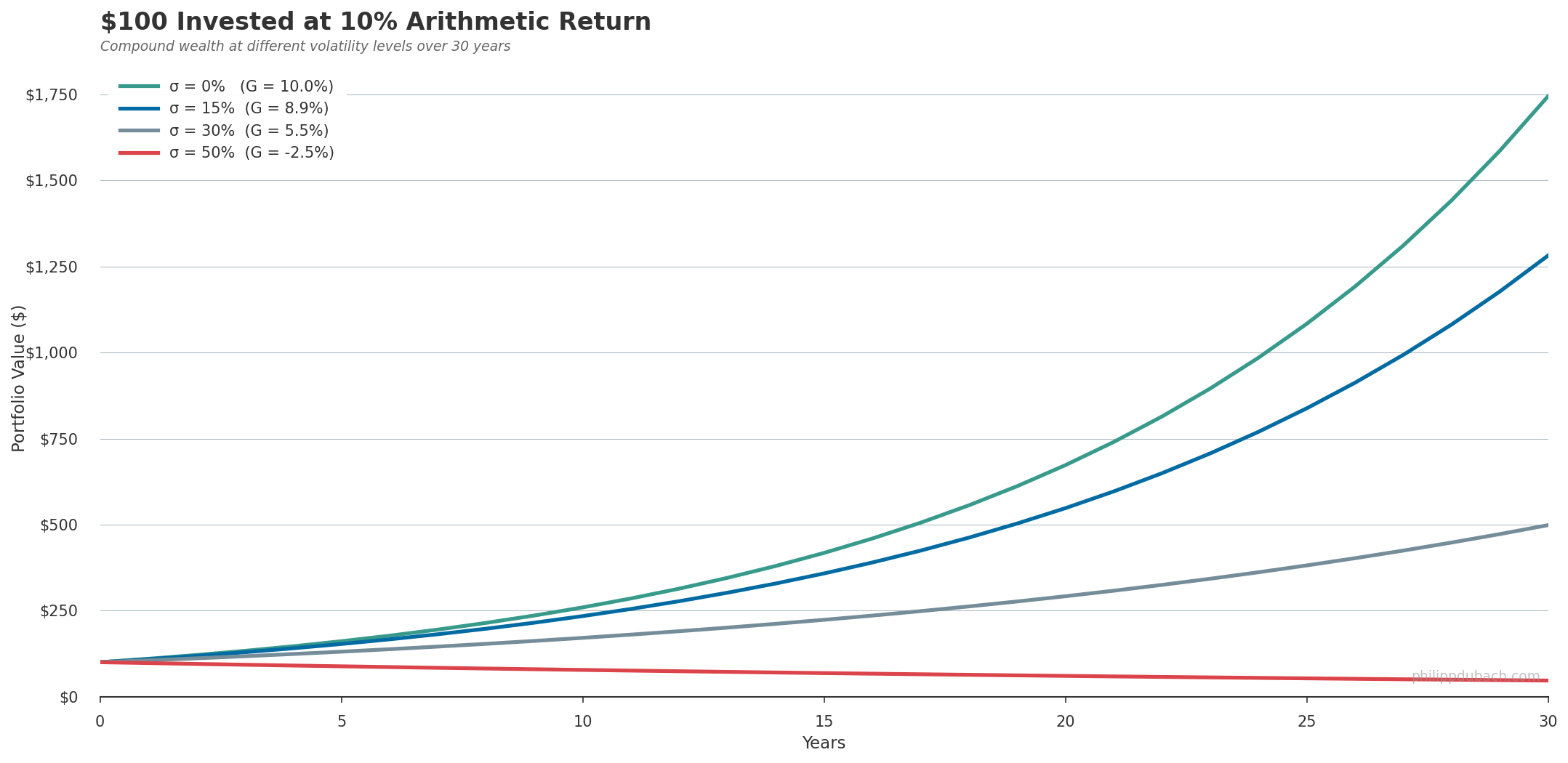

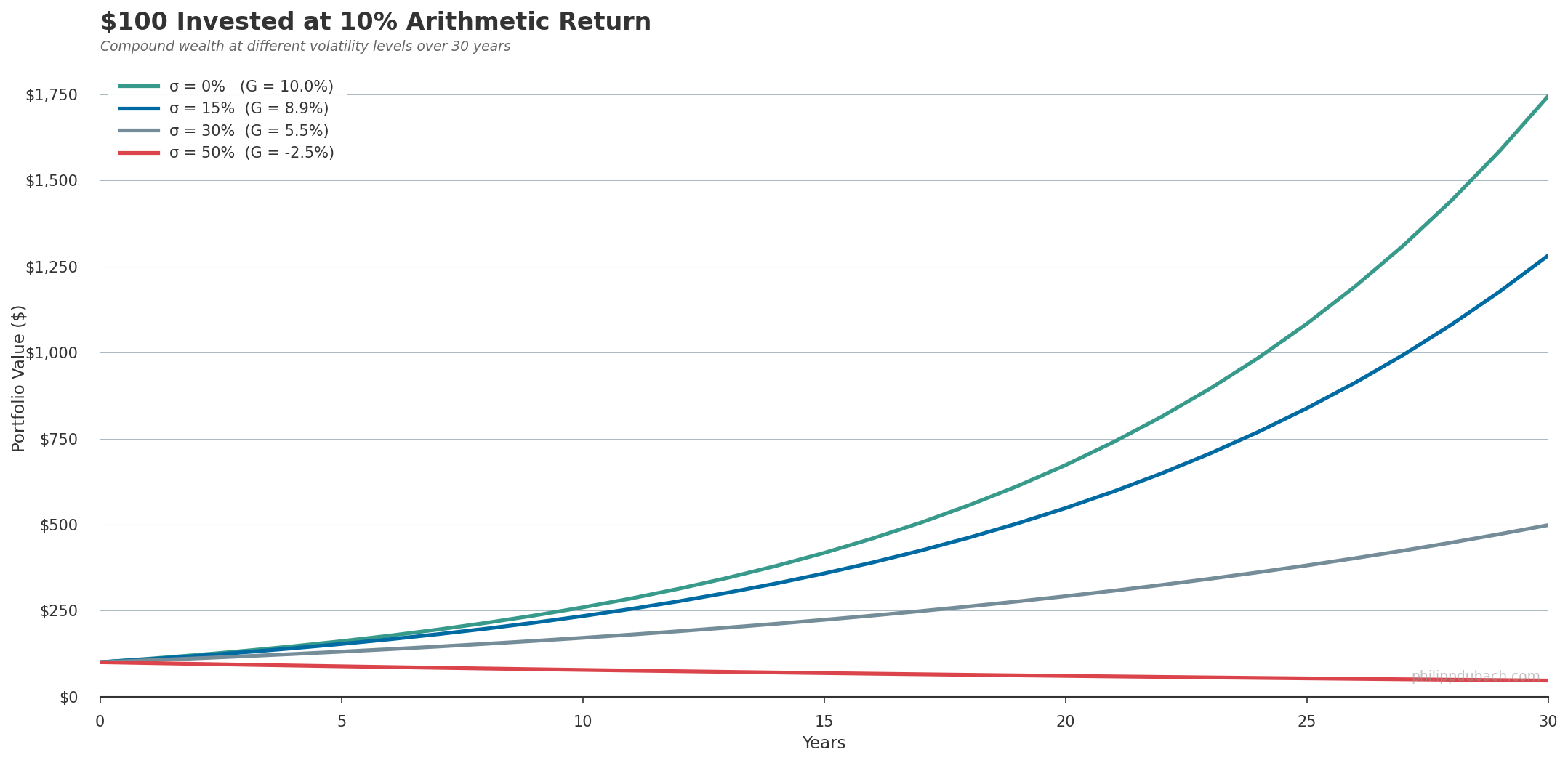

Same 10% arithmetic return, different volatility. After 30 years, the zero-volatility path reaches $1,745. At 15% vol, $1,280. At 30%, $498. At 50% vol you have lost more than half your money despite averaging +10% per year.

Same 10% arithmetic return, different volatility. After 30 years, the zero-volatility path reaches $1,745. At 15% vol, $1,280. At 30%, $498. At 50% vol you have lost more than half your money despite averaging +10% per year.

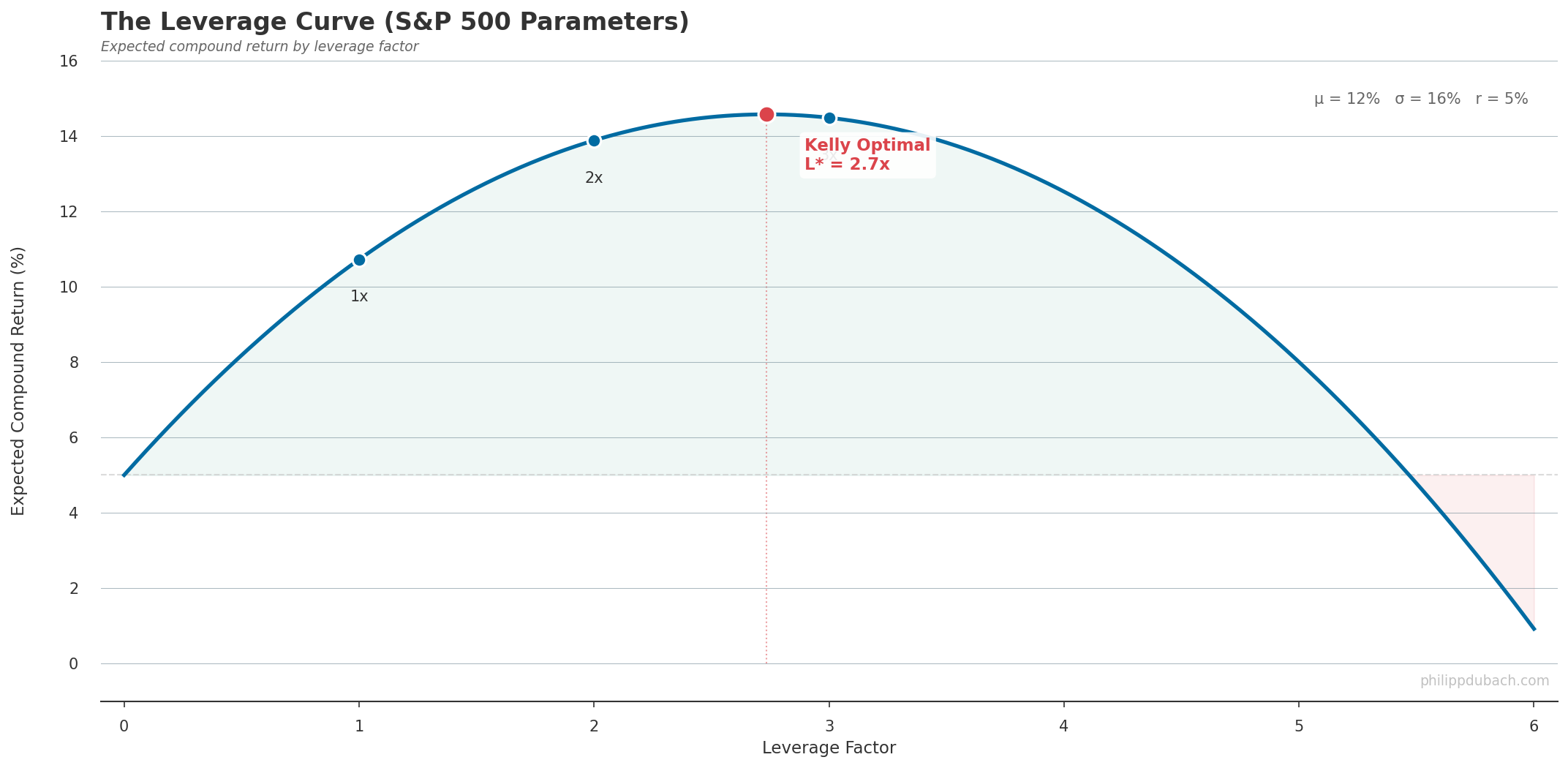

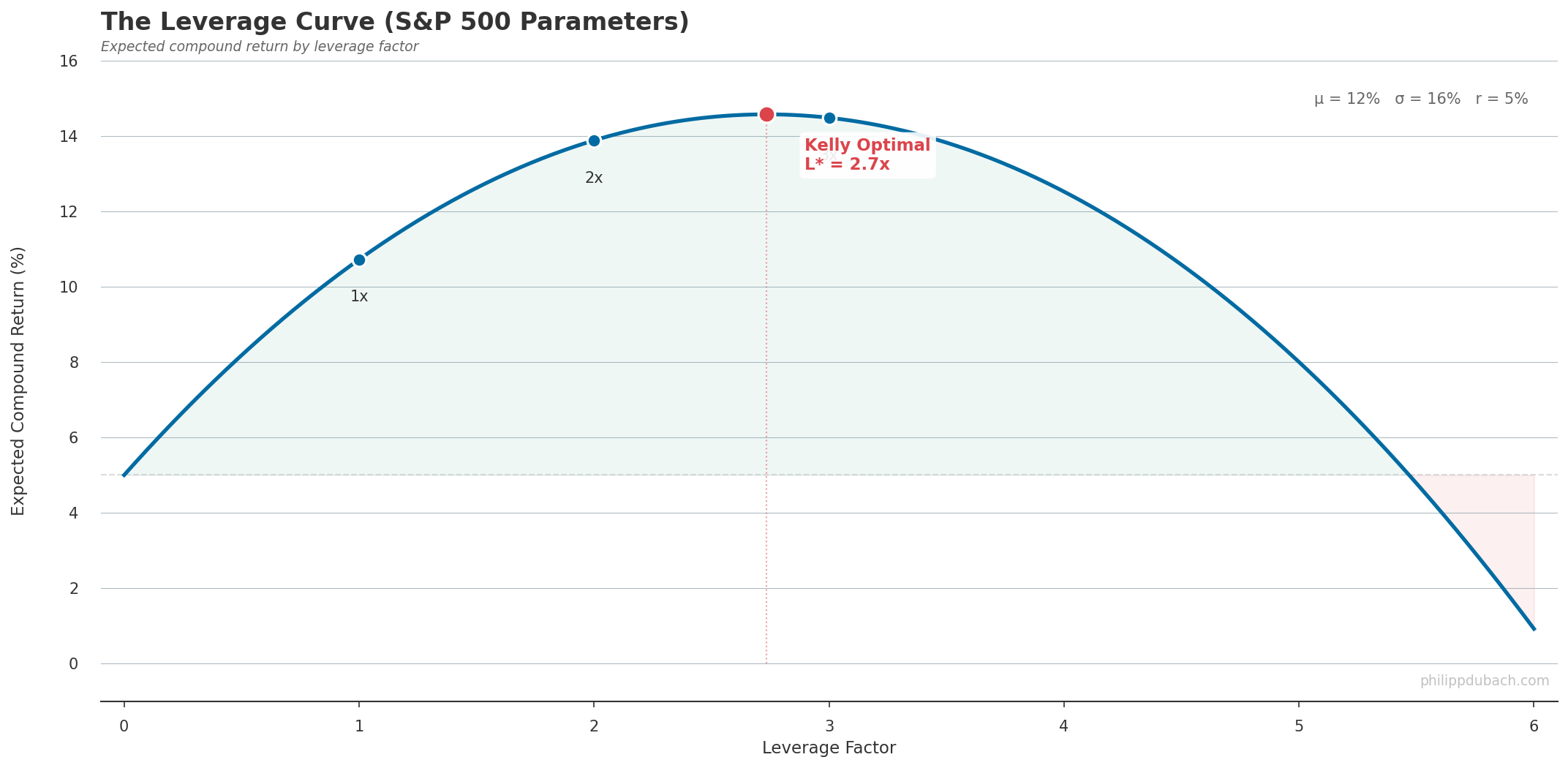

Now apply leverage. If you lever an asset by factor L, the arithmetic return scales linearly (Lμ) but the variance drain scales quadratically (½L²σ²). The compound return becomes:

$$G(L) ≈ r + L(μ − r) − ½L²σ²$$Take the derivative, set to zero. The leverage that maximizes compound wealth:

$$L^{\ast} = (μ − r) / σ²$$For the S&P 500 with roughly 7% excess return and 16% vol, L* comes out to about 2.7x.

This is the Kelly criterion (which you might know from utility theory or gambling heuristics but in fact, as we see here, it falls straight out of the variance tax formula.) Beyond Kelly, every dollar of additional leverage costs more in variance drain than it earns in expected return. The curve bends over and eventually goes negative. In practice, most practitioners use “half-Kelly” — sizing positions at L*/2 — because the formula assumes you know μ and σ precisely, and you don’t. Estimation error in either parameter can push you past the peak and onto the losing side of the curve. Half-Kelly sacrifices roughly 25% of the theoretical growth rate but dramatically reduces drawdown risk.

This is the Kelly criterion (which you might know from utility theory or gambling heuristics but in fact, as we see here, it falls straight out of the variance tax formula.) Beyond Kelly, every dollar of additional leverage costs more in variance drain than it earns in expected return. The curve bends over and eventually goes negative. In practice, most practitioners use “half-Kelly” — sizing positions at L*/2 — because the formula assumes you know μ and σ precisely, and you don’t. Estimation error in either parameter can push you past the peak and onto the losing side of the curve. Half-Kelly sacrifices roughly 25% of the theoretical growth rate but dramatically reduces drawdown risk.

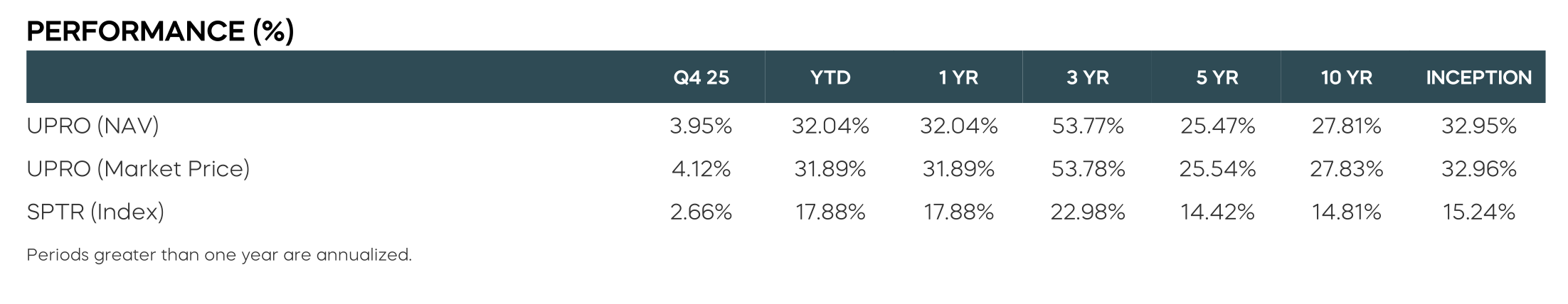

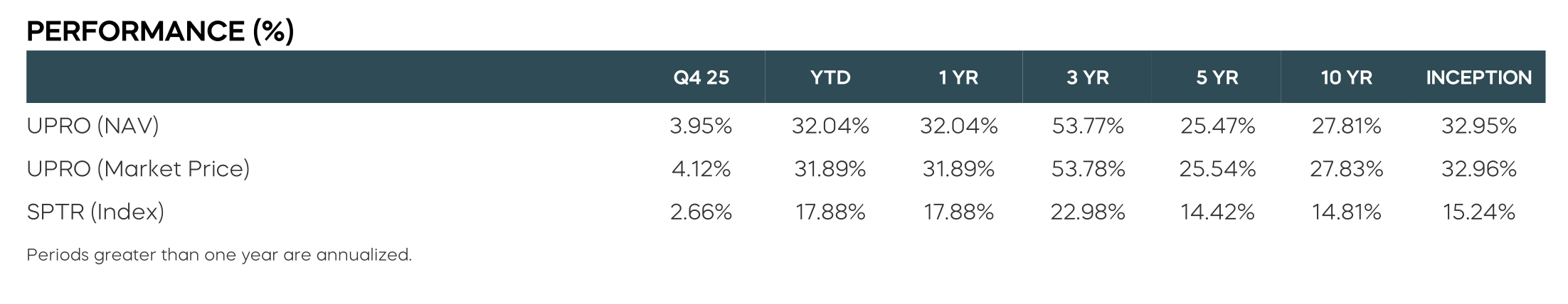

You can see this play out in practice. ProShares UPRO, the 3x S&P 500 ETF, has returned roughly 28% annualized over the past decade during one of the strongest bull markets in history. The S&P 500 compounded at about 10% over the same period. Linear 3x leverage would imply roughly 30%. Variance drain accounts for the gap, and that was in a favorable environment. In 2022, when the S&P fell about 19%, UPRO dropped 70%. The effect is even starker in higher-volatility underlyings: ProShares TQQQ, the 3x Nasdaq-100 ETF, sat roughly flat from its 2021 highs through early 2025 while the unlevered QQQ had long since recovered — a textbook case of variance drain overwhelming the leverage premium in a choppy market.

You can see this play out in practice. ProShares UPRO, the 3x S&P 500 ETF, has returned roughly 28% annualized over the past decade during one of the strongest bull markets in history. The S&P 500 compounded at about 10% over the same period. Linear 3x leverage would imply roughly 30%. Variance drain accounts for the gap, and that was in a favorable environment. In 2022, when the S&P fell about 19%, UPRO dropped 70%. The effect is even starker in higher-volatility underlyings: ProShares TQQQ, the 3x Nasdaq-100 ETF, sat roughly flat from its 2021 highs through early 2025 while the unlevered QQQ had long since recovered — a textbook case of variance drain overwhelming the leverage premium in a choppy market.

The same half-sigma-squared shows up across finance. It is why stock prices follow log-normal distributions, not normal ones. Why put options cost more than equidistant calls. Why the Black-Scholes d₁ and d₂ terms carry a ½σ²t adjustment. Why a $100 stock’s true geometric midpoint between $150 up and $50 down is not $100 but $86.60, because ln(150/100) = ln(100/66.67). Wherever returns compound and volatility is nonzero, the variance tax is being collected.